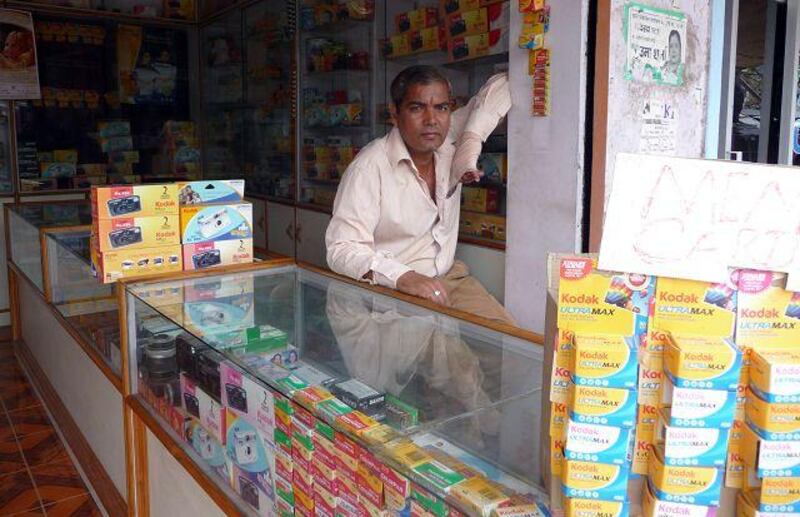

RISHIKESH, INDIA // The daily flood of Indian families into the holy city of Rishikesh is PL Kothari's boon - and part of a lifeline for a fading technology. Mr Kothari sells the trademark yellow and green boxes of Kodak and Fuji film to pilgrims, who snap shots of ashrams and take family portraits on the iconic Lakshman Jula, a footbridge that crosses over the sacred Ganges as it flows down from the Himalayan foothills.

While he is seeing a trend towards more people using their mobile phones to take snapshots these days, purchases of film and film-based cameras at his store have remained constant, he said. Nationally, demand in India for film is falling by roughly 30 to 35 per cent a year, according to Koji Wada, a marketing adviser at FujiFilm India, but that decline - mostly in urban centres - is not universal, he said. That is good news for Kodak and Fuji, who have seen demand for film plummet over the last decade with the advent of digital cameras. This week, Kodak retired Kodachrome, its first commercially successful colour film, after more than 70 years of production.

Some of the world's most famous colour photos - including that of Sharbat Gula, the "Afghan Girl" whose photograph by Steve McCurry appeared on the cover of National Geographic magazine in 1985 - as well as many family slide shows in the 1960s and 1970s have been printed on Kodachrome. However, it was the only film in which the dyes that bring colour to the images had to be added during processing. "There's this whole infrastructure around Kodachrome beyond just the film," said Grant Steinle, the vice president of operations at Dwayne's Photo in Parsons, Kansas, the only lab in the world that processes the film. "You might have 20 different components ? and you have to do ongoing analyses on the chemical constituents in the chemicals you're using. Kodak is the only company that manufactures the dye set, and they're discontinuing that as well."

Of course the catalyst for all of this is digital. Kodak said it earns 70 per cent of its profit from digital. Worldwide, internet habits have played a large role in the move to digital. In the West and other parts of Asia, millions of people share their photos on social networking sites. "Facebook is the largest depository, if you will, of digital images right now," said Gary Pageau, of PMA, a US-based trade association for the photographic industry. "It's the largest photo site there is."

Despite the country's strengths in information technology, less than five per cent of Indians have ever used the internet and only about four per cent actively go online, according to figures published in January by the internet and Mobile Association of India. That is low compared to other countries, such as China, where more than 20 per cent of the total population uses the internet, according to government statistics. More than half of all Americans went online last month alone, according to figures from Nielsen Online.

In addition, the vast majority of Indian internet users live in cities, which may explain why rolls of Kodak and Fuji film are especially popular in the countryside. Rama Malik, of Kodak India, said the decline her company sees in otherwise strong film sales is "primarily in the urban markets" - the same ones that she sees "transitioning to digital". Interestingly, there has been minimal decline in the demand for photographic paper, according to Fuji's Mr Wada, which suggests that digital photographers in India may still regularly print out their pictures.

Mr Wada said the most popular type of photos in India - even at the village level - are of weddings and other special events, where the prints remain the purpose of the shot, whether the professional photographer uses a film or digital camera. Although, as Mr Kothari, the shop owner in Rishikesh noticed, more people are using mobile phones for snapshots, the phones themselves cannot replace a good camera, Mr Wada said, based on his observations of both the Japanese and the Indian markets.

Phones can offer higher mega-pixels "but quality is not based only on that", he added. "It is necessary to have a good lens and software to get better photos." Phones and cameras have different uses, said Ms Malik, of Koadk India: phones may capture spontaneous images, but people will always prefer cameras to photograph new babies or weddings. There is little doubt that India will eventually go digital.

Mr Pageau, of the industry group, said it was just a matter of when. "There comes a point - and in different countries it's a different point - where the value of digital is far superior to that of analogue for most people in most cases, and then the market chooses," he said. "There's never been a chemical process that has survived the onslaught of a digital one." Mr Pageau still sees opportunity in film, but he does not see the technology sustaining itself worldwide over the next 20 years. Indeed, the retiring of Kodachrome may prove an early major step in the shift.

Mr Kothari would agree - although he is not worried about his customers going digital any time soon. Rolls of film in India can cost anywhere from less than 100 rupees (Dh7.5) to more than 200 rupees, and Mr Kothari estimates that he sells about 10 a day. He also usually sells one or two 500-rupee film-based cameras. He has started selling digital memory cards, too, but for now, he says, only foreign tourists buy them.

* The National