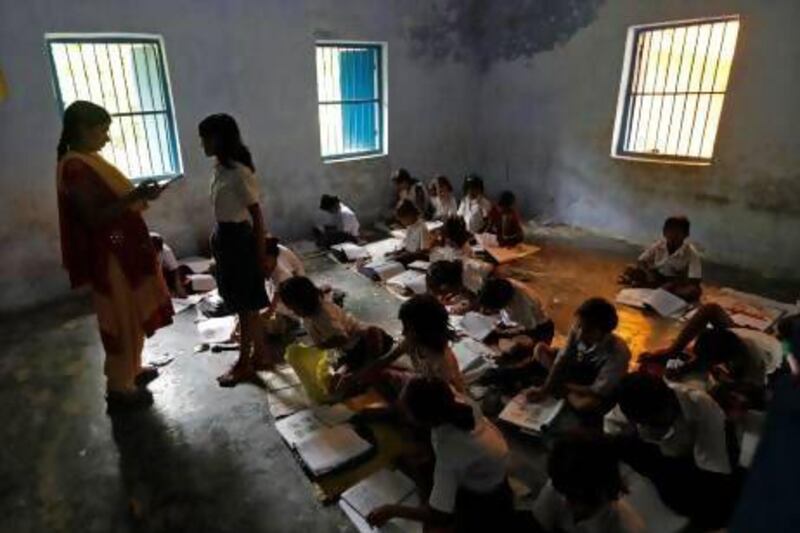

NEW DELHI // The school's only classroom has no benches, lights or fans. The blackboard is a black painted rectangle on the wall.

This is the village primary school in the eastern state of Bihar where 23 children were fatally poisoned last week after eating an insecticide-tainted lunch.

Books scattered across mats on the floor of the empty room are reminders of the chaos that ensued as the children started feeling ill and losing consciousness.

While the tragedy focused attention on the failings of a nationwide scheme to provide free school lunches, it has also brought to light the abysmal state of government-run education in rural areas.

"For primary kids, sitting on a bench is just a dream. In most rural government schools, you won't see one," said Ranjan Kumar Mohanty, who runs the People's Cultural Centre in Orissa state, a non-profit group that works on rural issues.

Like the school in Dharamsati Gandawa village in Bihar, thousands of state-run schools in India lack proper infrastructure. The school kitchen where the deadly midday meal was cooked is simply a charcoal stove made up of stacked bricks outside the classroom.

"There is rampant corruption everywhere," Mr Mohanty said. "The funds for building schools are siphoned off. Money allocated for the midday meal is stolen. School inspectors are available but they don't inspect."

The midday meal programme is one of the government's most ambitious schemes, aimed at boosting literacy and tackling malnutrition in a country where more than half of the children are undernourished. It is supposed to benefit about 120 million children at 1.2 million schools across the country.

But if it has encouraged enrolment, the programme has done little to compensate for the sparse capacities of rural schools to serve their students.

There is an acute shortage of teachers, and those present are ill-equipped to handle the duties. The school buildings are sub-par. And there are no mechanisms in place for proper monitoring, educators said.

"The biggest victims of the educational system are those living in rural areas," Anupam Hazra, an assistant professor of the department of social work at Assam University, wrote two years ago.

"Children in rural areas continue to be deprived of quality education owing to factors like lack of competent and committed teachers or lack of textbooks. A large number of teachers refuse to teach in rural areas and those that do, are usually underqualified," he noted.

According to the government's 2010 annual status of education report, 96.5 per cent of children between 6 and 14 in rural areas are enrolled in school, of which 71 per cent attend government schools.

Attracting enough teachers has proven far more difficult. More than half of the 13,000 schools surveyed faced a shortage of teachers.

India's Right to Education Act, implemented in 2010, which guarantees schooling for children between the ages of 6 and 14, stipulates that the student-teacher ratio in primary schools should be 30:1 by 2015, but there do not appear to be enough teachers.

"What you are seeing in Bihar and some other Indian states is that teaching assistants step in because the teachers who are appointed do not want to work in rural areas. Sometimes, they don't even show up for their posting," said Kumar Rana, the project director of the Pratichi Institute in Kolkata.

On average, government-employed teachers in rural areas earn 4,000-6,300 rupees (Dh246-387) a month, Mr Rana said - half of what teachers in state-run city schools make.

A 2010-2011 survey of Bihar schools by the Pratichi Institute found that most of the 150,000 teachers the Bihar government claimed to have appointed were actually teaching assistants, Mr Rana said.

In Orissa, 79,715 of the 167,948 teaching positions available are vacant, according to Mr Mohanty.

"The states are still trying to fulfil the norms because they are unable to attract the teachers," he said.

The education act empowers village leaders or panchayats - elected local councils - to file complaints to their state's education department about any shortcomings in government schools, such as lack of teachers or infrastructrure and the school food.

"This has yet to happen. They have a role to play but I don't think they know how to. The panchayats have received no training or instructions," said S Jeyaraj, director of the Rural Institute for Development Education in Tamil Nadu.

At the school where the poisonings occurred, the headmistress and one other teacher taught all the pupils from grades one to five, all of them in the same classroom.

The other teacher was on maternity leave at the time of the incident, leaving the headmistress to teach and run the entire school, as well as being responsible for supplying the grains and cooking oil for the midday meal, which were stored at her home, according to a government inquiry report.

"She has administrative work, classes to manage, a kitchen to run. All these problems of the education system have been brought forward with this case," said Mr Rana.

"Whatever the government claims, there has been no elemental change in education delivery or infrastructure."

[ sbhattacharya@thenational.ae ]

twitter: For breaking news from the Gulf, the Middle East and around the globe follow The National World. Follow us