BEIJING // After 11 years in Australia, Li Xiaoxue decided it was time to come home to China.

Life in Melbourne was good, but with her home country transforming at unprecedented speed, Ms Li was keen not to miss out.

"I wanted to do something for the country during this rapid development. If you're living abroad, you're just looking at the development," she said.

Originally from Beijing, Ms Li, 31, moved to Australia when she was 16 and completed her school, undergraduate and postgraduate studies before working in accountancy.

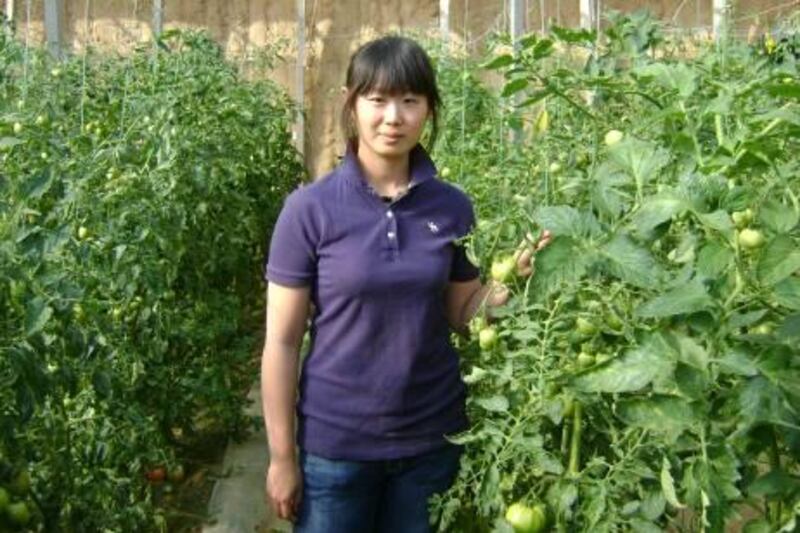

She came back four years ago and works just north of the Chinese capital as vice general manager of her mother's company, Organic Farm.

"Chinese culture has changed," she said. "It's modernised. It's closer to western culture, but still different in so many ways."

Ms Li is among what is thought to be a growing wave of Chinese people who went abroad but are returning as China's economy develops and standards of living improve.

It is a trend the authorities welcome. There has long been concern about the "brain drain" of the country's brightest, with the majority of Chinese who studied overseas remaining abroad.

Two years ago the Chinese government launched a "Thousand Talents" programme offering financial incentives to high-flying overseas Chinese who return.

The aim is to lure back 2,000 of the best bankers, academics engineers and others within a decade.

The number of returning students appears to be increasing, according to comments this year from Wang Xiaochu, the vice minister of human resources and social security.

Mr Wang said 100,000 came back last year, up 56 per cent from 2008, although the increase is likely to be partly because more Chinese now go abroad to study.

In Shanghai, reports indicate there are as many as 4,000 businesses started by returning students.

As well as attracting returning Chinese - often called "sea turtles" for their penchant to travel across the sea and return home - the country is also acting as a magnet to foreign-born ethnic Chinese who never lived in the country.

Official figures are not released, but the phenomenon is widely discussed in the media.

Wendy Leung-Baumann, 36, a British-born Oxford University graduate, moved to China six years ago and runs a brand consultancy in Shanghai.

"In Europe, where I was before, everything is more or less stable and less exciting," she said.

For people such as Ms Leung-Baumann, for whom China is to an extent a foreign country, adapting is not always easy. Her language skills, for a start, were "very poor".

"It was difficult at the beginning. Everyone expected me to know certain rules and customs, but you can't," she said.

Life is easier now. The married mother of two is fluent in Chinese and familiar with the cultural norms.

Integrating properly does require commitment, said Chen Xin, a professor in the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. If the main interest in moving to China is financial, the experience "may not be good for them".

"There are no obstacles in law or social custom in China to bring difficulties for them. The only question is if they're willing," he said.

"If their parents are second or third generation [overseas], that's a little bit difficult because the language and culture is quickly westernised."

Even Chinese-born people can find it hard to fit in if they have been away a long time.

Patrick You, 47, a Shanghai-based freelance interpreter, returned to China in 2003 after 12 years in Canada working as a traditional Chinese medicine practitioner. While he found the transition relatively smooth, some friends did not.

"It's very difficult for people. Some have very high expectations. They want to come back, but the reality is changing so quickly," he said.

"Also, your overseas experience doesn't guarantee you a job. In the early 1990s, it was very easy for a person with overseas experience to get a job. Now, the Chinese companies are more experienced with international business practice. They're more demanding."

Even if someone has integrated into Chinese society on their return, Ms Li believes living abroad will have changed them.

It is no surprise then that when she married last month it was to someone who had also lived overseas. Her husband spent more than a decade in Japan.

"You're used to the way of living …and the way of thinking," she said. "I think I connect more easily with people who worked or lived overseas for some time."