DHARAMSALA, INDIA // In a draughty dormitory for newly arrived Tibetan refugees in the northern Indian town of Dharamsala, six-year-old Choekyi curls up asleep against her father, exhausted after a three-week journey by lorry and by foot from their village in Central Tibet. Travelling illegally, often under the cover of night, Choekyi's father risked being thrown into prison, or worse, if they had been caught. But for the 37-year-old farmer, the dangers were worth it to secure for Choekyi, not her real name, the Tibetan education she cannot receive back home.

"I want her to learn about our culture and religion. At our local school, the Chinese language is dominant. The children are not taught Tibetan poetry or literature," said Ngawang, preferring not to give their real names for fear of retribution against their family in Tibet. "China is trying to restrict us so that we will wilt away." He could not have known it when he left home, but his arrival in Dharamsala - the seat of the Tibetan government-in-exile - would coincide with the largest meeting of the Tibetan diaspora in its six decade struggle against Chinese rule.

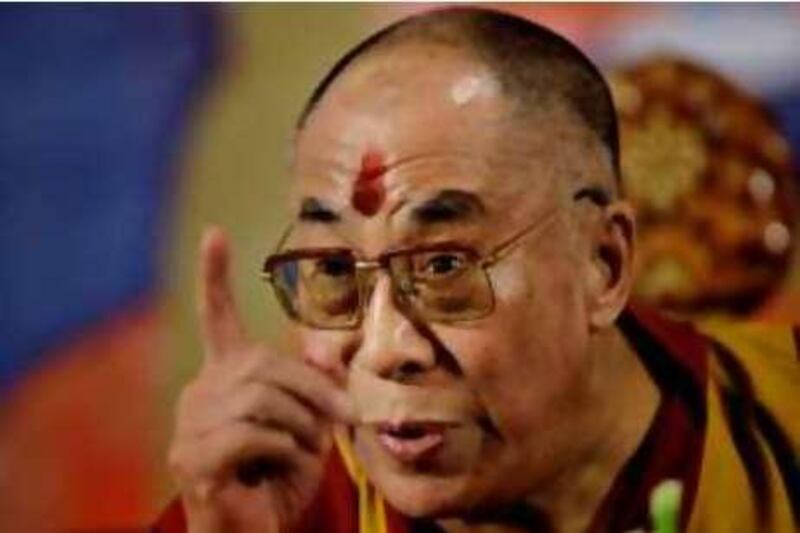

Responding to a call from the Dalai Lama, 600 leading exiles will gather here today for a six-day conference to discuss the way forward for their movement in light of what they see as an increasingly desperate situation in Tibet. "Tibetans are being handed down a death sentence. This ancient nation, with an ancient cultural heritage, is dying," the Dalai Lama said in Japan this month. "Suppression is increasing, and I cannot pretend that everything is OK." For more than 20 years, the exile movement has been guided by the Dalai Lama's "middle way", which calls for "meaningful autonomy" within China, rather than outright independence.

Last month, however, the spiritual leader, who fled Tibet in 1959 following a failed uprising against Chinese rule, said he had "given up" on the policy because "there hasn't been any positive response from the Chinese side". Now, the Dalai Lama has opened up every aspect of struggle for debate, issuing only a one-line agenda: "To discuss the issue of Tibet in the light of the recent upheavals and the repercussions in the international arena." The "upheavals" mentioned in the document are the bloody anti-government riots that began in Lhasa, the Tibetan capital, in March this year and spread to other cities in the region. Since then, the Dalai Lama has come in for much criticism from those who say the protests were evidence that the "middle way" has failed.

Many participants in the meeting - which can only recommend policy change - will be arguing for the Dalai Lama to resume calls for independence for the first time in almost three decades. "We have wasted 29 years with no result," said Karma Choephel, 59, speaker of the parliament-in-exile. "The body of people who support independence has grown." Some, however, worry that talk of independence plays in to the hands of the Chinese, who have always said the Dalai Lama is "insincere" in his calls for autonomy. This month, an eighth round of talks between Tibetan envoys and Chinese officials in Beijing ended with Zhu Weiqun of the Communist Party's United Front accusing the Dalai Lama, who won a Noble Peace Prize in 1989, of plotting "apartheid and ethnic cleansing". The Chinese also ruled out any greater autonomy for the region, which they said has been part of their territory for centuries but which Tibetans say was under rule from Lhasa for hundreds of years prior to 1950. At 73, many in Dharamsala, said the Dalai Lama's real reason for holding the meeting is to get the community to take greater responsibility for the cause while he is still alive and to relieve him from the burden of decision making. While he is in good health for his age, he has been hospitalised twice this year - last month he underwent an operation in Delhi to remove kidney stones - and his elder brother, who helped secure US Central Intelligence Agency support for Tibetan guerrilla fighters, died in New York in September. Without a clear legacy some activists and politicians fear the movement could splinter after he dies. This, said the experts, is what China is waiting for. "The Chinese have been so successful at dividing these people. There are more and more tensions," said Robbie Barnett, who teaches Tibetan history at Columbia University. But while differences exist, reverence for the Dalai Lama still runs deep. Most Tibetans see the "middle way" as his personal policy and are reluctant to criticise it. In the end, say participants in the conference, the most likely outcome from the meeting is a statement of support for the Dalai Lama, who threatened to resign in March unless his followers ceased their violence. "A statement that he is our unequivocal leader would alone be beneficial in dealing with the Chinese," said Dawa Phunkyi, a member of the Tibetan parliament-in exile. Whatever the result, the conference is likely to have little impact on Choekyi and her father. In a month he will attempt the dangerous journey home to his wife and younger son. He does not know when he will see Choekyi again. "I am leaving her here so she can serve His Holiness," he said, pulling at a string of orange prayer beads in his hand. "The struggle should continue." hgardner@thenational.ae