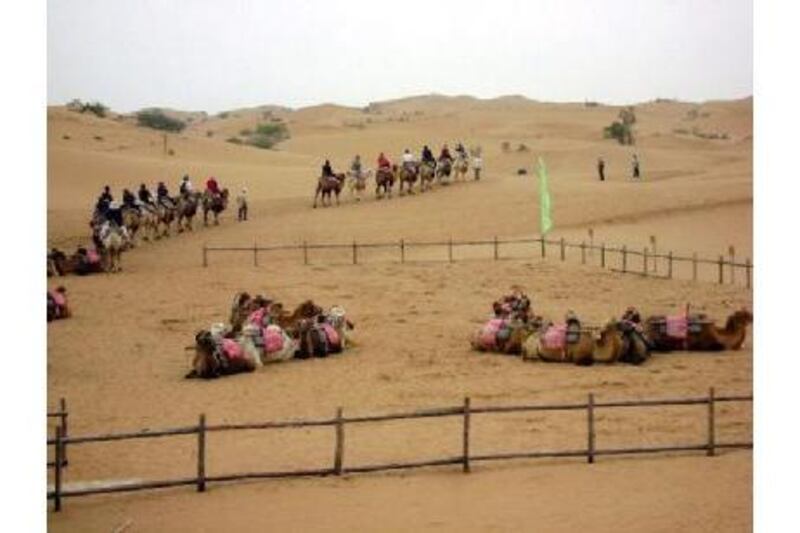

SHAPOTOU, CHINA // On the fringes of the Tengger Desert, a rolling landscape with golden sand dunes that could be straight out of the Arabian Peninsula, China is waging one of its several battles against desertification.

The work carried out at Shapotou, a sparsely populated area close to the languid waters of the Yellow River, has long been heralded as a success story in a country where droughts, agriculture and the demand for water put pressure on fragile ecosystems.

The battle in this part of Ningxia province is very much a practical one: it centres on protecting a railway line that runs through Shapotou, just north of the Yellow River, ultimately linking Urumqi in the far west with Beijing in the east. By planting shrubs south of the bare dunes and helping soil to form through checkerboard straw frames placed on the sand, China has kept at bay the encroaching desert. The trains continue to run, but it is a never-ending struggle.

"Controlling the sand is needed to protect the Yellow River and the railway, but it needs a lot of money," said Bu Xingai, a director in the foreign affairs office of the Ningxia Hui autonomous region, as it is officially known. "It needs water. Even if it's watered every day, maybe after an hour it's dry." This project has worked well enough, over several decades, for the authorities to showcase it by setting up an outdoor park for visitors. Mr Bu insists that in Ningxia the total size of deserts is remaining stable, at about one-third of the province's land area.

But academic studies into the work at Shapotou have conceded that, although anti-desertification measures mean some land in the area has become suitable for agriculture, the demand on resources is worryingly high. In China as a whole it is harder to question the level of effort put into controlling desertification than it is to ask whether the methods employed have always been the right ones. In particular, some question whether the national frenzy for planting trees to hold back deserts might be misplaced.

China said this year that it had achieved its goal, set in early 2009, to increase forest coverage to 20 per cent of the country's land area from just more than 18 per cent. The State Forestry Administration had said it was spending 60 billion yuan (Dh32.9bn) a year on tree-planting. With the general population urged to get involved, more than 500 million people are said to have planted more than two billion trees between 2008 and 2009.

Over the next 40 years, such efforts are expected to continue, with the aim of doubling, to 42 per cent, the proportion of the country's area that is forested. Forests planted to control the Gobi desert in China's far north are sometimes known as the Great Green Wall. Last month Jia Qinglin, a member of the Communist Party's central politburo, called on the authorities to plant more trees as "ecological screens" to prevent natural disasters. Experts said the mudslides in August in Gansu province that killed almost 1,500 people could have been partly the result of deforestation on nearby hillsides.

China hails its tree-planting as a measure to combat climate change, saying the rapidly growing species that are planted, among them birch and poplar, capture more carbon than indigenous species. However, there are concerns from some researchers that, far from working against global warming, these new forests of non-native trees may be less effective at capturing carbon than the agriculture sometimes sacrificed in their favour.

"When it comes to planting trees and trying to improve the vegetation situation, the important thing is it must be local species rather than alien species," said Tom Wang, a spokesman for Greenpeace China. The organisation believes much tree-planting has taken place without assessing the myriad effects alien species could have. In any case, the local effects of tree-planting might struggle to work in the face of wider environmental change, according to the group.

"They are planting a lot of trees, but things are getting much drier every year," he said. Even at Shapotou, a study last year by two scientists from Lanzhou University in neigbhouring Gansu province blamed "global change" for an increase in floating dust in the area, suggesting that local efforts to control desertification could be compromised by wider environmental trends.

"When it comes to climate change, we need to look at the problem in a long-term perspective and try to improve the country's energy sector," Mr Wang added. "It's not about one place. It's not just Ningxia's problem, it's the whole country's problem."

Mr Bu in Ningxia acknowledged how widespread the problem was, but insisted schemes such as those at Shapotou are worth pursuing. "The desert covers too large an area in China, so these projects needs continuous effort if we want to beat the environment," he said.