SYDNEY // Aboriginal leaders have accused the Australian government of plotting to steal tribal land under a controversial policy to combat child abuse in remote settlements. Troops, police officers and medical teams were sent to more than 70 indigenous communities in Australia's Northern Territory in June 2007 to oversee new restrictions. The intervention was an emergency response to a damning report about widespread child exploitation and paedophilia in isolated areas. Bans on alcohol and pornography were brought in and strict controls introduced on how Aborigines could spend welfare payments to try to stop family budgets being frittered away.

The government has also threatened to withdraw funding to aboriginal communities deemed "economically unviable". The radical reforms have been welcomed by some communities but others have said the measures are draconian and intended to force Aborigines from their traditional homelands. Many Aborigines have already started to move away from their communities to escape the restrictions and the perceived nannying by the state, a move some say was intentional.

"We see the intervention as a land grab," said Ray Minniecon, an aboriginal pastor. "We thought it wasn't about the protection of our children but was more about the ways in which the government could take our land for economic purposes or, as many of our people think, about dumping nuclear waste or for mining." Ministers have strongly denied the allegations but furious indigenous leaders have threatened to close Uluru, one of Australia's most popular tourist destinations, to protest against the government's approach.

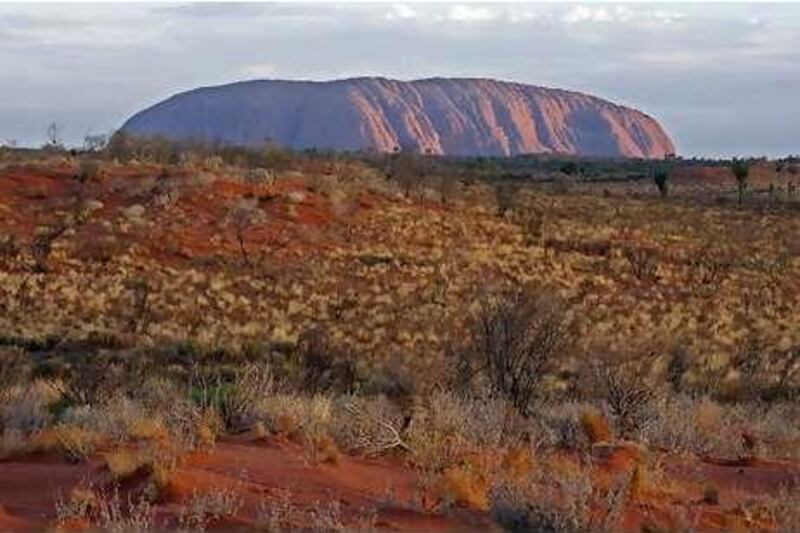

Uluru, formerly known as Ayers Rock, is a giant sandstone formation in Australia's dusty red centre and is managed by its custodians, the Anangu people. "We've got to take some affirmative action to stop this rubbish, racist piece of legislation," said Vince Forrester, a community elder. "We're going to stop it. We're going to throw a big rock on top of the tourist industry. No one will climb Uluru ever again."

The colossal red rock is a World Heritage-listed site south-west of the desert town of Alice Springs and is sacred to Aborigines, who sense the undying power of ancestral spirits. Land lies at the heart of indigenous culture in Australia. The earth is seen as a living, breathing mass, full of secrets and wisdom. Uluru was created, according to one theory, after a battle between rival tribes. The earth was consumed by so much pain and sorrow, that it rose up to form a rock the colour of blood.

"The land is our mother," explained Mr Minniecon. "When a baby is born one of the rituals the mother does is she takes the placenta and she buries it in the earth and that one little act makes sure that the child is connected to the country. "Old people can point to a certain spot on the map and they'll say 'look, that's where my mother laid me down, that's my country, that's where I come from. That's who I am'."

These rock solid beliefs have been severely tested by more than 200 years of European settlement. Australia's colonial masters brought with them attitudes to land that Aborigines found impossible to understand. "There's never been a view in aboriginal culture that land is a commodity," said Chris Cunneen of the University of New South Wales. "It's inconceivable that you could buy and sell the land from which you come. It would be like arguing that you could buy and sell your mother or your father."

Australia's European colonisers declared that the empty continent belonged to no one. They had the view that because the indigenous people did not work the land, they therefore had no connection to it. It was a convenient doctrine, which allowed the settlers to help themselves to vast chunks of territory. Dispossessed and alienated, Australia's Aborigines have suffered ever since. They make up two per cent of the national population and endure disproportionately high rates of ill health, unemployment and imprisonment.

The indigenous land rights movement began to agitate for change in the 1970s. Negotiated settlements with the authorities allow tribal groups to live on customary land in large parts of northern Queensland, the Northern Territory, Western Australia and parts of South Australia. Last September, the Githabul people of eastern Australia won a 10-year battle for ownership of pristine rainforests and a sacred mountain in one of the country's biggest land treaties, which gave them the right to hunt and carry out traditional ceremonies.

Lindsay Bookie, the chairman of the Central Land Council, a statutory body that protects the interests of Aborigines, believes that encouraging young people to understand their organic connection to the earth could stop them succumbing to alcohol and drugs. "Aboriginal kids in the bush are very keen on the ceremonies and to understand their country but not our younger people in town," Mr Bookie said. "They're into their European ways and sniffing petrol. The drug problem is pretty bad, young people smoking dope all the time.

"The land is the mother of creation. I feel proud when I look at the land and talking to people about it. Our spirituality is still strong." @Email:pmercer@thenational.ae