THIMPHU // Saffron-robed monks wander the streets of Thimphu, where elaborately painted buildings feature lucky symbols like tigers and phalluses, all under the gaze of a huge gold Buddha atop a mountain overlooking Bhutan's tree-lined capital.

Premium-paying tourists have long eulogised Bhutan's unspoilt charms, its peace and its pristine environment, but the Himalayan kingdom, famed as the "last Shangri-La", and for using happiness to measure its success, is no idyll.

Its economy is struggling, with shantytowns emerging in urban centres, packs of wild dogs roaming freely, and beggars on street corners.

Bhutan, wedged between India and China, spends far more on imports than it earns, banks are cracking down on cheap credit after a recent debt-driven spending boom, and youth employment has surged to 9.2 per cent as teenagers abandon farming for urban life.

The government is trying to cut the number of people living below the poverty line to 15 per cent of the population from its current 23 per cent, according to its own figures.

Encouraging more tourists would bring in cash, but the government will not abandon its long-standing policy of limiting visitor numbers by accepting only those who pay $250 (Dh918) a day in advance.

"Bhutan will never be a mass destination," said Chhimmy Pem, head of marketing at the Tourism Council of Bhutan, formerly the Department of Tourism, which implements the government's tourism policy. "Our target will always be the high end visitors."

After paying for accommodation, travel, food and a guide, $65 of that $250 goes to the government. The policy was adopted to prevent tourism destroying Bhutan's unique Buddhist culture and traditions, but some politicians say protection from the outside world is no longer needed.

"Tourism was a real threat in the past, but that threat has gone," Tshering Tobgay, head of main opposition group, the People's Democratic Party, said. An increasingly consumerist Bhutanese society, he said, is changing regardless of the influence of sightseers. "It is us Bhutanese ourselves who are now putting our traditions and culture at risk."

Bhutan adopted a "high end, low volume" tourism policy when the reclusive nation first opened its borders to foreigners in 1974. That year just 300 visited.

In 2011, Bhutan welcomed around 64,000 people, according to figures released by the Tourism Council of Bhutan this month. By contrast, more than 600,000 people visited nearby Nepal in 2010, official Nepali figures showed.

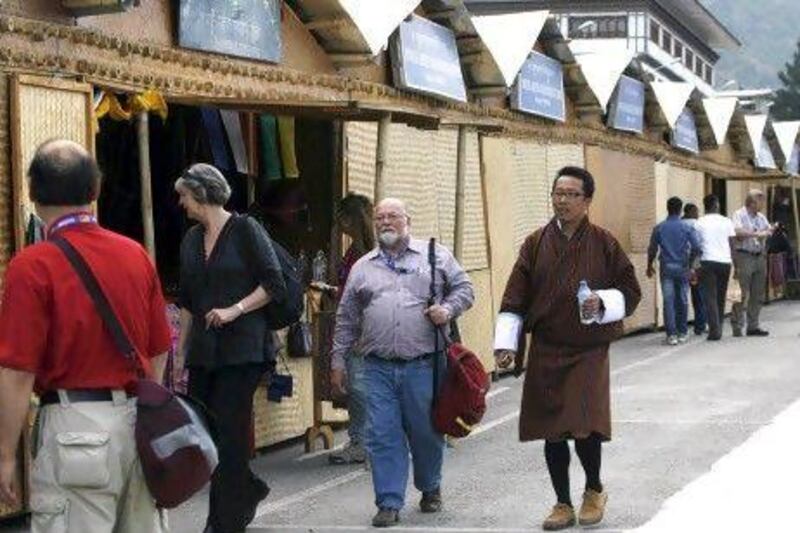

In contrast to Nepal and India, where backpackers who live on a few dollars a day are welcomed, luxury resorts are more Bhutan's style.

Management consultancy firm McKinsey was commissioned by Bhutan to examine its economy, and recommended in 2009 that the country should attract 250,000 tourists by 2014.

The government decided this target was too ambitious, and instead wants to bring in 100,000 a year by the end of 2012.

Combined with visitor spending on extra services and handicrafts, the Tourism Council estimated the industry contributed nearly 10 per cent of GDP in 2011, making it Bhutan's second biggest earner. Power exports, mainly to India, account for 40 per cent of national revenue, and a quarter of GDP, according to the Asian Development Bank.

Sonam Dorji, secretary-general of the Association of Bhutanese Tour Operators, said early fears over the culturally and environmentally destructive effects of tourism had faded, but concerns over numbers had not.

"The tourists who come here are well travelled, and cultural tourism is their major interest, so they travel to the villages to see local festivals and stay in traditional homestays," he said. "This brings money to local economies and supports these traditions which could die out otherwise."

About 70 per cent of Bhutan's 700,000 population survives through subsistence farming. Electricity and roads are yet to reach all of the country, and the latest Gross National Happiness survey, conducted in 2010, found only 41 per cent of Bhutanese were classified as "happy".

In an interview in May, prime minister Jigmi Thinley said Bhutan could not cope with the recent phenomenon of debt-fuelled consumerism which has outstripped economic output, forcing the government to cut spending and consider raising some taxes.

But Bhutan is a country in transition. The younger generation is abandoning traditional dress in favour of jeans, T-shirts and tattoos, and most young Bhutanese are on Facebook.

It is a major shift for a nation that only allowed television and internet access in 1999, and still bans the sale of tobacco.

This is the where the tension lies: tourists, so important to the economy, enjoy the exclusivity of Bhutan, and they fear that if the pace of progress increases, they may find the very things that draw them there are jeopardised.

"There are no queues here and tourism has not left a mark," said American tourist Jennifer Logsdon, a human resources executive from Boston who was enjoying Bhutan's ancient monasteries and fortresses dotted across the country.