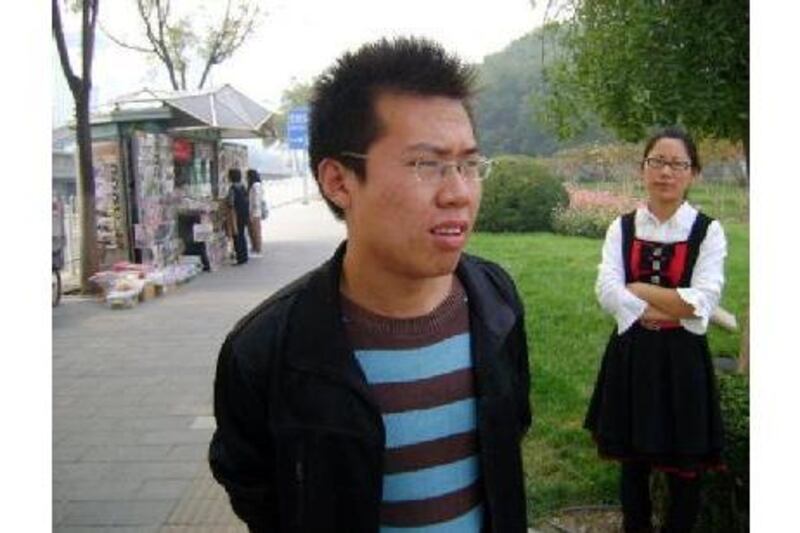

BEIJING // Zhang Fei wants more from life than his parents ever did.

The 27-year-old, who sells jewellery at a shopping mall store, is looking to better himself, a decade after moving to Beijing from a province far to the south of the capital.

"I am trying to work and earn money to buy an apartment and a car, or even to get married in Beijing," he said.

For now, Mr Zhang can only afford to rent a room in a tatty area of unrenovated courtyard houses east of the city centre. It costs him 800 yuan (Dh439) a month, but he still holds out hope for something nicer. "To live in your own place is very important for the younger generation," he said.

"Their ambition comes because they want a better life in Beijing, but the big problem is their income is not enough."

There are millions of similarly ambitious young migrant workers in China, and experts say this new, educated generation has demands and expectations that the economy, despite its rapid expansion, might struggle to meet.

As a graduate, Liu Xiaojing might not be classified as a typical migrant worker, but since the number of Chinese completing university annually has grown six-fold in a decade to 6.3 million, many jobs performed by people once bracketed as migrant labour are now taken by graduates.

A 24-year-old who moved to Beijing three months ago, Ms Liu is eager to find a better job and increase her salary. She takes home 2,000 yuan a month as an English teacher, but believes she should be earning at least 50 per cent more.

"The older generation, they preferred just to work here and send money back to their hometown," she said. "But we have more opportunities. To find a good job or even run my own business; to earn more money is important for me."

Ms Liu's frustration with her present circumstances is echoed in the views of Li Tao, the founder of a non-governmental organisation for migrants called Facilitator.

He said today's migrants are, if anything, less content than their parents' generation because their expectations are much greater.

"In the past, they had very limited kinds of job - the female migrant worker's choice was between working as a nanny or in a restaurant," he said. "The previous generation were probably more easily satisfied because they had very limited education. They were satisfied if they could find a job with a stable income.

"Now there are all kinds of jobs, from insurance companies to real estate agents. But they're still not very satisfied. [Job satisfaction] has probably even worsened."

Most young migrants have at least completed high school, Mr Li said, and often have also gone to a vocational college. More are bringing their children with them, increasing demand for services in the large cities, he added. While incomes have grown, so have the costs of living.

Another source of concern is that although today's migrants are more aware of their rights, thanks particularly to the internet, they have little ability to demand these rights are respected.

"They have very limited legal channels they can go through to seek legal aid," Mr Li said. Just as the ambitions of migrants are growing, so are their numbers. Some estimates put the current number at more than 200 million, but by 2050 the figure is predicted to reach 350 million.

"They tend to stay in the cities longer than the first generation, who hoped to go back to their hometown," said Zhang Huimin, director of programmes for Compassion for Migrant Children, a Beijing-based NGO.

On average, they stay in their adopted cities for more than five years, with nearly one-fifth remaining for more than a decade. A difficulty still facing migrants, especially those looking to settle, is the hukou system, a form of residence registration that limits the provision of services such as health care and education to locals.

Although the abolition of these rules is discussed, Chen Xin, director of the youth and social issues studies department at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said they were needed to limit the numbers migrating to major cities, maintaining a "dual system" of metropolitan and provincial registered residents.

"We should still keep another part living the traditional way in the rural areas, far away from the modern market economy," he said, adding it was not feasible for all of China's 1.3 billion people to enjoy a high standard of living in urban areas.

Despite the hurdles, many young Chinese will continue to be driven to the big cities by their ambition.

Ms Liu's friend Fu Caiwan, a 24-year-old telephone salesman also from Hebei, said Beijing offers "more opportunities to find a good job. The older generation of migrant workers, they preferred to earn some money [to send back to] their children. But for the younger generation, we are after a better life."