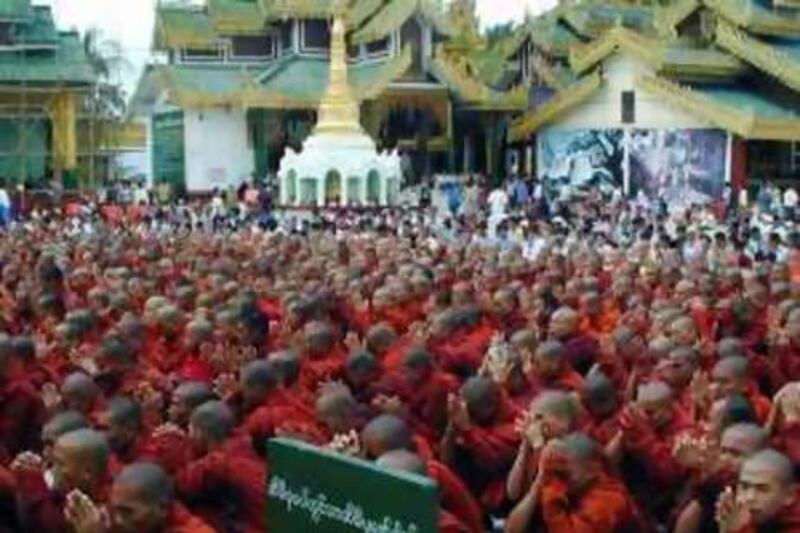

YANGON // In many ways this is a story of failure. Of a government that failed to deliver on long-made promises of freedom and democracy; of a people who stood up not once but twice against repression, and were cut down both times; and of an international community that champions human rights but has so far failed to turn rhetoric into reality. A year ago, spiralling inflation and growing political repression in Myanmar led tens of thousands of people, including Buddhist monks and nuns, to take to the streets in peaceful protest. The mass demonstrations, known as the Saffron Revolution for the colour of the monks' robes, were brutally suppressed.

On Sept 27 2007, soldiers and riot police, armed with assault rifles, tanks and smoke bombs, opened fire, killing about 50 people. Thousands were rounded up and detained. It was as if a mirror had been held up to reflect the 1988 pro-democracy demonstrations, or 88 Generation uprising, when thousands of students protested to demand multiparty democratic elections. The dissent two decades ago was similarly smothered; thousands paid with their lives.

Although the demonstrations helped pave the way for elections two years later, in which the opposition, the National League for Democracy, won a landslide 82 per cent of the vote, the junta refused to acknowledge the results. The NLD's leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, was put under house arrest and those members of her party who were not detained, fled into exile. Ms Suu Kyi later won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Twelve months have passed since the last protests, and those in Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, face an even bleaker future. The junta's hold on power has tightened and progress towards democracy and economic stability seem more elusive than ever. "Our country is good, but our government is not good," said Maung Aung, a 30-year-old electrical engineer in a rare moment of openness on a train from Mandalay, in Myanmar's heart, to Myitkyina, the capital of northern Kachin state. "We have no democracy. We want democracy. Last year they [the junta] killed many people by shooting. The junta were like animals," said Maung Aung, who like many people in Myanmar interviewed for this article refused to use his real name.

"Our government is spread everywhere. We are afraid of them." Thatched bamboo roof homes skirt the region north of Mandalay. Herons swoop and dart into lush emerald patchworks. These are paddies of rice, the region's main agricultural crop. But behind the idyllic rural landscapes and the warmth of the people, Myanmar has become a byword for suffering. Human rights groups regularly highlight the junta's systematic use of rape, forced and child labour, torture and imprisonment to maintain power. The average person earns less than US$1 (Dh3.67) a day. Although the junta does not publicise its military or public spending, economists estimate the regime spends about $330 million a year on defence and arms, more than double the amount it spends annually on education and health care combined.

In the former capital, Yangon - the site of some of the largest mass protests last year - the fading evening light only partly hides potholed side roads strewn with litter. Men gossip and laugh at street-side teashops, constantly aware that every word could be used as a weapon against them. One foreign aid worker said people, in desperation, had taken to informing on one another. "Even if they are not pro-junta, a Burmese person may need to win the favour of a government official to get an everyday thing done," the aid worker said. "So if they find out who you are, they may tell."

Nevertheless, ordinary people are eager to talk about what is going on inside their country and have a hunger for knowledge about the outside world. "Do you think people in Myanmar are brave?" asked Aung Aye Win, also not her real name, a 22-year-old film student who took part in last year's protests. "I don't. If they were brave ? how many people are there in Myanmar? If they all join together, what can they [the junta] do?"

Aung Aye Win said young people were not interested in politics. "It's not just fear, they just don't know and don't question," she said. She, like many of Myanmar's 55 million people, relies on international news channels for information. Satellite hookups to Al Jazeera, the BBC and foreign radio stations feed a country starved of access to the outside world. The junta, or State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), sporadically tries to block the channels, which works for a couple of months before the connections quiver back into life.

The regime's English-language newspaper, The New Light of Myanmar, warns its readers against believing the propaganda peddled by "certain internal and external anti-government elements, self-centred persons and unscrupulous elements". It singles out the BBC as a "skilful liar attempting to destroy the nation". The junta has good reason to feel paranoid. It long ago lost the battle for the hearts of its people, depriving them of democracy, human rights, education, free speech and health care since it seized power in a violent coup in 1962. Since then, the SPDC has slowly closed its people off from the outside world.

Its leader, Senior Gen Than Shwe, 75, became chairman of the junta in 1992 and has implemented increasingly isolationist political and economic policies. Foreigners seen to be interfering in "state affairs" face deportation and sometimes short periods of imprisonment. Citizens of Myanmar face an even harsher fate. Many are imprisoned or ill-treated for "anti-state" political activities after being tried in closed courtrooms.

Students Myo Min Zaw, 31, and Ko Aye Aung, 33, remain in jail after being imprisoned for demonstrating for improvements to the education system and for the 1990 election results to be honoured. They were given 52-year and 45-year sentences respectively. Research by the NLD shows that of the 5,000 people detained during and immediately after last year's protests, 700 remain in custody. The Thailand-based Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Myanmar), which provides support for the families of political prisoners, says 2,097 people are detained in Myanmar for their political views, including Ms Suu Kyi, 63, who has spent much of the past 18 years confined to her Yangon home.

"The social and political situation is worse since 2007," said Win Min, a student revolutionary who helped lead the 1988 protests before fleeing to exile in Thailand, and is now a lecturer of contemporary Myanmar politics at Payap University in Chiang Mai, Thailand. "I'm talking about political repression and arrests of activists. The military is not going to change by itself. They will crack down if there are demonstrations again."

After their shock loss in the 1990 elections, the regime began designing a new constitution, part of its self-styled seven-step "road map to democracy", that it promised would culminate in elections in 2010. The constitution took 14 years to finalise, and in May it was put to a national referendum, just weeks after a cyclone devastated the Irrawaddy delta and killed more than 130,000. The junta said 92 per cent of the population voted in favour of the new draft. Most western governments decried the vote as a sham and the draft a backwards step for democracy. The new constitution sets aside 25 per cent of non-elected MP seats for the military and allows the armed forces to carry out a coup if the generals deem it necessary.

The junta has also refused to negotiate with the NLD. The resulting political deadlock, which the United Nations has tried but so far failed to mediate a course through, has added to the difficulties. Four visits over the past year by Ibrahim Gambari, the UN's special adviser to Myanmar, have yielded few results. Ban Ki-moon, the UN secretary general, admitted this month that the regime had failed to improve on democracy and human rights.

Win Min said for democratic progress to happen, there needed to be more pressure from the international community, especially from the country's key trading partners, such as China. But there also needed to be sympathetic ears within the military and government, he said. "So far, we don't have pragmatic and moderate leaders in the military ? I believe there are some moderate leaders in the military but they cannot show they are moderate at the moment because the top leaders are very authoritarian. It may happen when Than Shwe dies or resigns, that's one way ? I hope there will be a change but the problem is I don't see any significant change in the immediate future but maybe in the long term," he said.

But time is not on Myanmar's side. Economists have predicted its economy, and its people, will continue to suffer. Last year's protest happened after the junta removed subsidies on fuel, thereby doubling diesel prices and increasing the cost of compressed natural gas by 500 per cent, which forced public transport charges to rise by 100 per cent. The regime gave no warning of the increases and people woke up the next morning unable to afford the bus fare to work.

Sean Turnell, an associate professor at Myanmar Economic Watch in the economics department at Macquarie University in Sydney, said inflation was now at about 40 per cent in Myanmar and would continue to rise. "The situation faced by the average person is quite considerably direr than it was a year ago and I think the economic situation is going to deteriorate further. "Myanmar has no reason to be poor, it has got a lot going for it. It's economic mismanagement by the government."

Despite the West's criticism of the junta's handling of last year's protests and greater calls for more dialogue with Ms Suu Kyi and her party, the junta has proved itself to be inflexible. Mark Canning, Britain's ambassador to Myanmar, warned that the international community was failing the country's people. "Unless there is a political settlement to this problem that embraces the opposition [NLD], the government and the ethnic minorities, then this country will continue slowly and steadily on its downwards slide and impact its neighbours including China.

"No one who knows this country is positive about its future. We have been trying to achieve progress since 1962, but we do believe change is possible given constant pressure on the regime." The NLD, however, wants to see stronger action taken. So far, sanctions have hurt only the Myanmar people, with the government continuing to benefit from the spoils of oil, hydropower and natural gas deals with international companies and the proceeds of its gem mining.

Nyo Ohn Myint, a spokesman for the NLD in exile in Thailand, said: "We are trying to challenge the regime's credibility at the UN. That will force the junta into dialogue and apply political pressure. The European Union and the United States cannot change the political landscape, we are the ones that can change it through political pressure and though a more harmonised approach with the mass movement inside Myanmar."

But whether the junta will see the light remains unknown. Its track record so far does not offer much hope. rsisodia@thenational.ae