Despite the Taliban’s announcement of a three-day ceasefire beginning on Friday, Eid Al Adha celebrations across Afghanistan remain sombre and muted. The increasing violence, failing peace efforts and swiftly spreading pandemic weigh on people’s minds in the capital Kabul and across the country.

On July 28, the Taliban announced a temporary truce for Eid Al Adha, instructing all fighters to refrain from attacking enemies unless provoked.

"All Mujahideen are instructed to halt offensive operations against enemy forces during the three days and nights of Eid Al Adha," Zabihullah Mujahid, the Taliban spokesperson, said in a statement on Tuesday. "However, if the opposition carries out an attack, they must be met with a strong response," he added.

This is the second ceasefire between the insurgent group and the Afghan government this year, and only the third pause in fighting over two decades of war in Afghanistan.

But with insurgent attacks continuing to cause high civilian casualties, Afghans are sceptical of the Taliban’s commitment to peace.

A car bomb detonated on Thursday, just hours ahead of the start of the ceasefire, left 18 killed and over 40 civilians injured in Logar, a province close to the Afghan capital. The Taliban has denied involvement in the attack but Afghan security officials claim to have evidence that a local Taliban leader was involved in the massacre.

This year has seen a rise in violence in Afghanistan, with the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) reporting a 33 percent increase in civilian casualites from Taliban related-attacks in the first half of 2020 compared to 2019.

As a result, many Afghans remain deeply cautious, even as they welcome the temporary truce.

“I was so happy when I heard about the ceasefire. it seemed like it could help pave the way for a permanent end of fighting,” Shkula Zadran, a 25-year-old women’s rights activist from Kabul said.

Memories of the Eid Al Adha ceasefire in 2018 has rekindled hopes for brotherhood and bonhomie. During that truce, the Taliban fighters entered into government-controlled cities and interacted with the locals they usually target, joining in with celebrations and taking selfies.

“That ceasefire was quite unusual and surprising. The Taliban were walking around the city, enjoying ice cream and food with locals. Some were even interviewed by female journalists. It was like a dream,” she recalled.

But less than 24 hours after the latest ceasefire announcement, Ms Zadran regretted raising her hopes. “I watched the aftermath of the explosion in Logar that killed so many innocent people. Now I feel this announcement of ceasefire is meaningless. The Taliban hasn’t shown real commitment and willingness for their actions,” she said.

Similar sentiments were shared across the country as Afghans mourned the loss of human life in yet another attack on civilians. “We can’t trust them. They might deny it, but it is so clear to us that Taliban killed my friends,” said Haroon, a civil society activist from Logar who lost five loved ones in Thursday’s attack—four of whom were from one family.

Haroon, who did not wish to share his real name for fear of reprisal, claimed the number of casualties was much higher than the government had declared. “What peace and what ceasefire are you talking about? I have a list of 143 people who were injured. Can you imagine the grief of a father who lost four sons in this attack?” he said, speaking between tears.

“The Taliban offer peace to Americans, but for Afghans, they call us kafir (disbeliever) and give [us] violence,” he said.

The Taliban has ramped up attacks on Afghans and government forces this year, despite promising to reduce violence in a deal signed with the US on February 29.

A quarterly report released on Friday by the US government’s oversight authority on reconstruction in Afghanistan expressed concern over mounting casualties.

According to the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) report, the months of April to June showed a 59-percent increase in civilian casualties in Afghanistan on the previous quarter, and an 18-per cent increase compared to the same period last year.

Amid this rising civilian death toll, many Afghans have simply lost hope. "Peace in this country is close to impossible," Ahmad Ali, a 21-year-old shopkeeper from West Kabul told The National.

“The last time they implemented such a ceasefire [in 2018], three days later they killed dozens of Hazara men in my village in Maidan Wardak. How is that peace?”

The Taliban has been known to persecute members of the Hazara community, a Shia minority group in Afghanistan.

Ali, who has only ever known war in his lifetime, has been an eyewitness to the growing insecurity in the country.

“I am only 21 but I can tell you tonnes of stories of explosions, roadside bombs and complex attacks that I have seen with my own eyes,” he said.

Ms Zadran, the women’s rights activist, says negotiation seems futile. “The Taliban are playing games with our lives… They want the Afghan government to release their prisoners but in return they are killing our people. For any negotiation there needs to be trust, but how can we trust them if they are not honest in their words.”

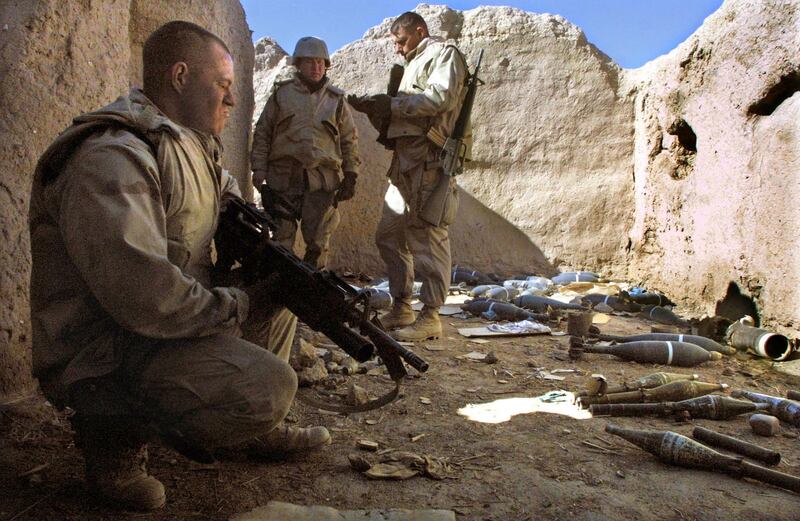

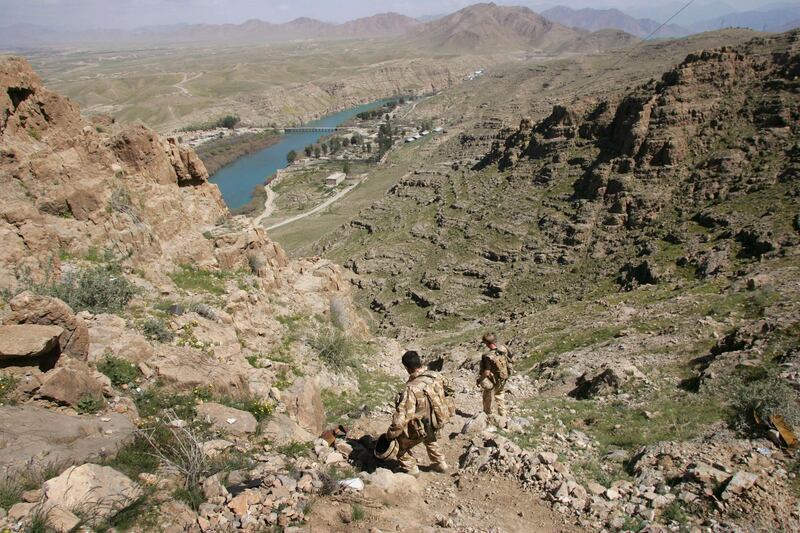

![Anti-Taliban Afghan fighters watch several explosions from U.S. bombings in the Tora Bora mountains in Afghanistan December 16, 2001. [Hundreds of al Qaeda fighters have battled to the death in a last stand in eastern Afghanistan, but their leader Osama bin Laden eluded the U.S. dragnet, Afghan commanders said on Sunday.]](https://thenational-the-national-prod.cdn.arcpublishing.com/resizer/v2/YCW5WFIGOZJVH2LWMZJZTLGUAQ.jpg?smart=true&auth=c19db2c42a968863762f0a49e2e7e5bde9fe9382f7764bcdd92b8aba7b1797cb&width=800&height=547)