American and Taliban representatives have agreed to resume talks again soon, as the adversaries appeared to edge towards an historic agreement ending America's longest war.

Six days of talks ended in Doha on Saturday with both sides saying headway had been made on issues including an American troop withdrawal and possible ceasefire, and they would use the momentum to press on quickly.

Discussions between US President Donald Trump's Afghanistan point man, Zalmay Khalilzad, and Taliban negotiators also included opening up talks to the Kabul government and ensuring Afghan soil is never again used to launch terrorist attacks on other states.

Mr Khalilzad said the talks in Qatar's capital had been "more productive than they have been in the past" and "made significant progress on vital issues". A Taliban statement used similar language, saying "negotiations revolving around the withdrawal of foreign troops from Afghanistan and other vital issues saw progress".

Mr Khalilzad was on Sunday due in Kabul to debrief president Ashraf Ghani, who has been sidelined from initial talks as the Taliban dismissed his government as a puppet administration.

Last week's talks appeared to be the best chance yet for finding a political settlement after 10 years of thwarted and piecemeal initiatives. Yet there were concerns in Afghanistan that the country should not be sold out in the rush for the United States to find an exit.

While the Doha talks appeared to have focussed on the key concerns of America and the Taliban, it was unclear how Afghanistan's fragile democracy would be treated. The prospect of on an end to violence which has killed more than 24,000 civilians since 2009 and more than 45,000 troops and police since 2015 is keenly welcomed by Afghans. But there are also fears American haste to withdraw will lead to abandonment and a repeat of the 1990s civil war.

Taliban negotiators have reportedly addressed the US' main motivation for its 17-year-long military campaign by providing assurances they will not allow terrorist groups such as Al Qaeda or ISIS to plot attacks from Afghanistan. The Taliban's harbouring of Osama bin Laden in the 1990s and refusal to give him up after the September 11 2001 attacks prompted the US invasion. At the same time the Taliban, still angry and distrustful after their ousting in 2001, have demanded assurances on an American military withdrawal. The time frame for a withdrawal and its extent are unclear, though unconfirmed reports said it would take 18 months from the implementation of the agreement.

The US is also pressing for a ceasefire and for the Taliban to start talking to their countrymen. “Nothing is agreed until everything is agreed, and 'everything' must include an intra-Afghan dialogue and comprehensive ceasefire,” Mr Khalilzad said.

Afghanistan's grinding conflict stretches back decades before American involvement however, said Haroun Mir, a Kabul-based political analyst. He said it was unclear how the Taliban would join Afghanistan's political system under any agreement and whether they would accept its democratic constitution. It was also unclear if they were prepared to join politics with factions they fought throughout the 1990s.

“Of course everybody is excited [about the talks] because ultimately this is something everyone is waiting for. But importantly the conflict in Afghanistan is not from 2001 it goes back to the early 1980s. Everyone is waiting to see because we have witnessed so many deals in the past and they have all unravelled.

“All those who fought the Taliban in the past, they don't feel comfortable right now. Are [the Taliban] sincere? Will they accept a truce, or will they just buy time to wait for the Americans to leave? These are the questions that honestly no one has answers to. How the Taliban will behave, will they act the same way they did in the 1990s?”

Unconfirmed reports that the Doha agreement would include an interim government have added to uncertainty. Afghanistan is currently preparing for its fourth presidential election since the Taliban regime was overthrown. Voting slated for July will see Mr Ghani again face his government chief executive, Abdullah Abdullah, at the polls.

Mr Khalilzad and his negotiating team have been under intense pressure from Mr Trump to find a way to wrap up America's war which the US president believes is a wasteful failure.

Mr Trump's patience appeared to snap in December when military officials said they had been told to begin pulling out half of America's 14,000 troops. That decision appeared to have later been reversed, or scaled back.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said reports from Mr Khalilzad were encouraging. The US was “serious about pursuing peace, preventing Afghanistan from continuing to be a space for international terrorism and bringing forces home,” he said.

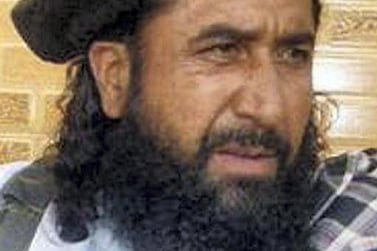

Expectancy for the resumption of talks was heightened after the Taliban said Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar would join as chief negotiator. The appointment of the former co-founder and number two of the Taliban who was released from custody in Pakistan in October has been seen as a sign of how seriously the militants are now taking negotiations.