He is Kabul’s go-to man for the kind of safety equipment you need in a terror attack or medical kits to stem the bleeding of a bullet wound.

Mustafa, whose name was changed to protect his identity, has built a successful business supplying security companies and foreign embassies with these items amid the instability since US troops led the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001.

But with US troops drawing down and the government talking to the Taliban about the future of the country, including a possible power-sharing deal, Mustafa is concerned the future of his business may be in jeopardy.

“I’m worried that I will face problems because I work with foreigners,” says the visibly nervous 26-year-old.

“The Taliban’s opinion is one of, ‘We are fighting against foreign security companies and the US military so why are you helping to save their lives?’” he says.

Afghan government calls for ceasefire as peace talks with Taliban begin

The Pentagon announced on Friday that US service personnel in Afghanistan had been reduced from 4,500 to 2,500 this month – the lowest number of US soldiers in Afghanistan since 2001 – despite an increase in Taliban violence across the country.

Territorial gains in recent weeks in the southern province of Kandahar indicate peace may not be a priority for the Taliban.

There has also been a spike in targeted killings across the country, which Afghan and US officials have blamed on the Taliban. Mustafa is concerned his work makes him vulnerable to such threats.

Building a business post-invasion

Mustafa’s father initially started out selling American food – predominantly ready-to-eat meals (MREs) supplied by the US military. He ran a shop in their home town of Bagram, where the largest US military base in the country is, before moving to Kabul in 2012.

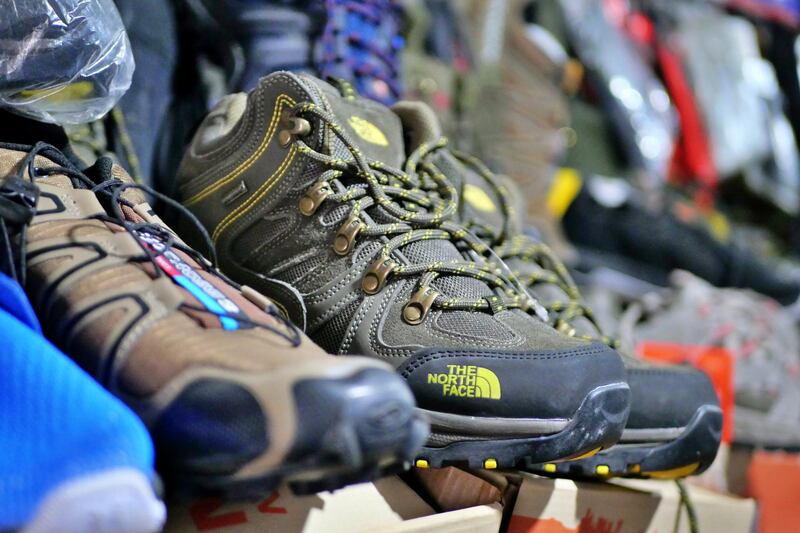

Nestled between embassies in the centre of the city, the business offering has now evolved to include top-of-the-range trauma first-aid equipment, and US military-certified safety apparel, such as flak jackets and helmets, as well as army-issue clothing.

His supplies come from security companies and military units when they leave Afghanistan and neighbouring countries, as taking surplus kit with them is costly.

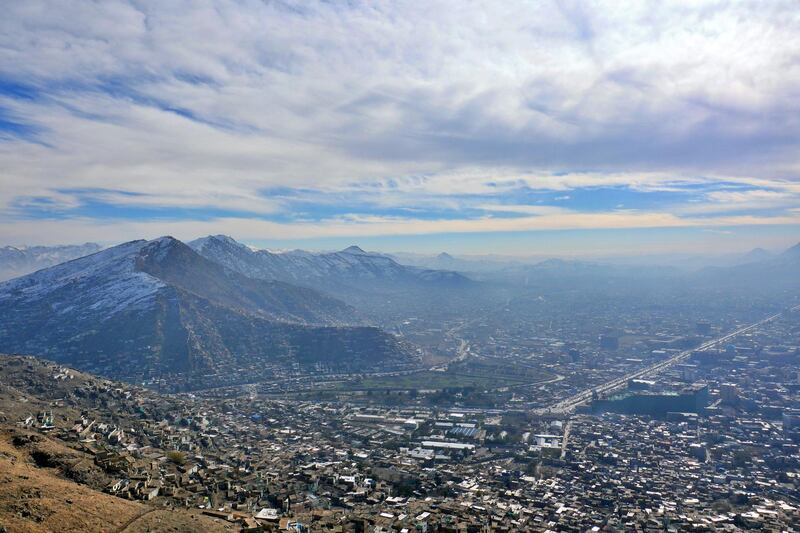

Mustafa’s biggest fear is the Taliban taking control of Kabul – a prospect he believes is more likely after the US troop withdrawals.

“The Afghan security forces don’t have the resources and equipment to defend against not only the Taliban, but also Daesh,” he says, using the Arabic name for ISIS.

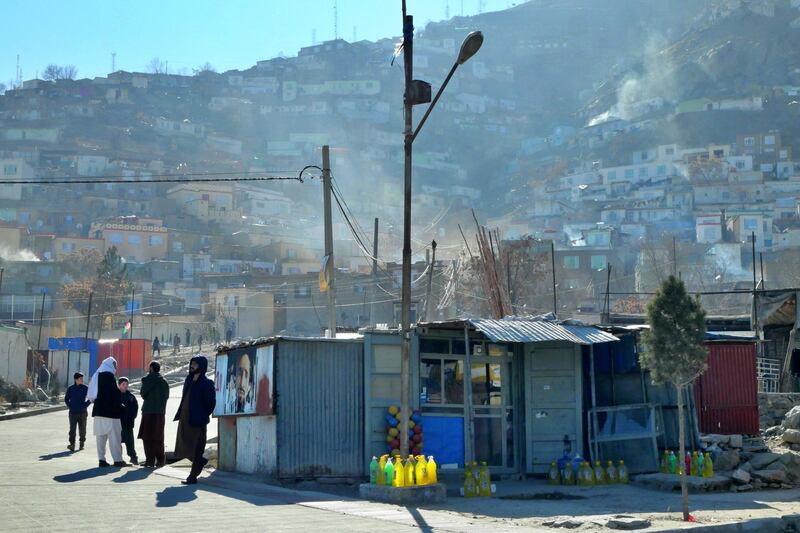

Kabul has experienced a spike in violence in recent months.

Explosions rock the Afghan capital on a near-daily basis as tensions peak amid Doha peace talks between the government and the Taliban.

More than anything, Mustafa is desperate for peace.

Newly married, the future remains uncertain, so he tries to focus on the here and now rather than worrying about what comes next.

Vacuum left by the US

If the US withdrawal extends to foreign contractors, businesses supplying security equipment to foreign companies operating in Afghanistan could be left with few new clients.

The US-Taliban agreement in February last year stipulated that private security contractors will also be removed from the country.

But Mustafa is not overly concerned that departing troops mean fewer sales – his best year for business was 2014 despite a US troop drawdown at that time.

International Crisis Group senior analyst Andrew Watkins pointed to the dependency of Afghanistan’s economic growth on international funding since 2001.

“As troop numbers and contributions rose, you saw an almost precisely corresponding increase in economic growth. It’s not as if all growth stopped after the 2014 drawdown of troops, but it did level out,” he says.

“This reveals how much the growth of the economy has been directly linked to the presence of international military forces. The hope is, things might change enough that the dynamics we’ve seen over the last 20 years won’t be applicable – if the peace process is successful then the previous rules may not apply,” he said.

Mr Watkins also points out that the Taliban claim to be willing to join the world economy – a U-turn on their stance during their previous rule in the 1990s.

Others see opportunities in the prospect of a power-sharing deal being reached between the Afghan government and the Taliban.

Everything you need to know about the Afghan deal

Niaz Mohammad Akbar, the owner of a medical supplies company, believes a power-sharing deal would be a positive step for businesses in Afghanistan.

His company, Aria Equipment, works with aid organisations and was commissioned to install a thermal screening system at Kabul’s Hamid Karzai International Airport and the Islam Qala land border into Iran, as part of Covid-19 prevention methods.

“If the peace talks are a success, my business will be able to expand into areas I’m not currently able to reach,” he says.

Shifting spheres of influence

Approximately 70 per cent of Afghanistan is not under government control and it is estimated that just under 20 cent is ruled by the Taliban, according to Long War Journal.

About half of the country remains disputed territory.

“I don’t think the Taliban can come in again with the same structure as they did when they were in power in the 90s,” says Mr Akbar, a father of six whose eldest daughter hopes to study economics next year.

“My people are not the people they were 40 years ago. They know about business, they have education, and knowledge from other countries.”

Afghanistan’s GDP grew by more than $15 billion between 2002 and 2019, to $19.29bn. Yet, corruption within the Afghan government and inconsistent enforcement of tax and regulatory policies has hampered economic growth.

“We had no formal trade relationships with other countries while the Taliban were ruling. The international community helped us to build this country to what it is today. We have developed drastically, but whether it’s enough is another question,” says Mr Akbar.

Like so many others, he says security is the biggest concern. Although he supports the US military’s withdrawal, he points out that the government forces are struggling with a lack of resources and technology.

“If we’re not safe, how can we focus on other things? If we have security, anything is possible.”

Fearing a return to the past

For Laila Haidari, simply being a woman puts her business at risk should the Taliban regain power.

The 41-year-old launched her Kabul-based restaurant, Taj Begum, about a decade ago, using the profits to launch a rehabilitation centre for drug addicts.

If her business faces difficulty, so too will the people who rely on her support.

“There were no women running restaurants at that time,” she says. “After the fall of the Taliban, a new political order was formed that helped women to trade, study and so on.”

That is not to say Ms Haidari has not faced significant challenges, which she attributes to being female, but the prospect of the Taliban regaining power is by far the biggest threat, she says.

During the Taliban’s previous reign, women were banished indoors and forced to wear the burqa at all times in public. The concept of female entrepreneurs was non-existent.

“Business is important for women because economic power gives women more rights and more involvement in politics,” says Ms Haidari.

For many women, being able to financially support their families means they are given an unspoken permission to be more independent – that could be simply spending time with friends, not wearing a headscarf, or living in their own places. If they lose their income, they will also lose their freedom.

“I support the US involvement because I believe in the values they have tried to instil here. But we have paid a heavy price for these values and now they are leaving defeated,” says Ms Haidari.