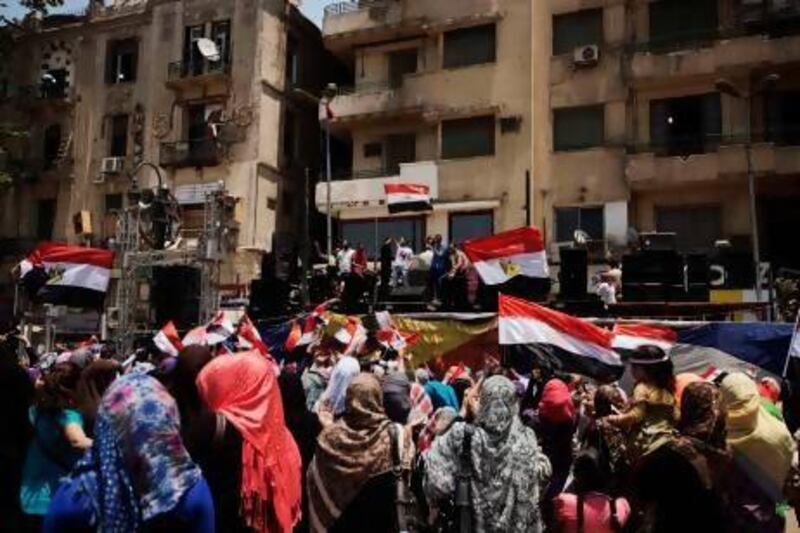

TUNIS // As Egypt's elected president was being deposed by the army, Tunisians were mesmerised by the fireworks in Tahrir Square lighting up their television screens.

Their uprising two and a half long years ago was the first in the region to kick out an autocratic leader and usher in a hopeful new era of democracy. After Wednesday night, that era was called into question.

"I don't know if it's right or not," said Nizar Bin Amira, 42, pulling on a water pipe in a cafe in the upmarket Nasr City area of the capital. "They elected him through right elections, and yet they went to the streets - it brings up the question of whether in any Arab Spring country, if they elect a president, they can go to the streets and bring him down again.

"That's not the way things should go."

The events in Egypt, the Arab world's most populous country and one of its most influential, have been greeted with mixed emotions in the countries where uprisings have called for democracy, or at least an end to corrupt autocracy.

For some, the sight of millions of Egyptians pouring onto the streets to hold a deeply flawed government to account was a triumph of democracy, or a sign of a backlash against Islamism. For others, the fall of an elected president - especially with the assistance of the powerful armed forces to deliver the final blow - was a stark sign of the difficulties of implementing democracy in countries with shaky economies, divided populations and feeble democratic institutions.

"There are some people who are inspired by what happened," said Lilia Weslaty, a journalist and political activist in Tunisia. "They want to kick out [the dominant, Islamist party] Ennahda ... some people hate the Islamists. They believe they are against human rights."

She pointed out that a group of young Tunisians had formed a group called Tamarod, or Rebel, named after one in Egypt that was a driving force behind the demonstrations marking the anniversary of Mohammed Morsi's presidency.

The group said on Wednesday in Tunis that it had collected about 200,000 signatures of people opposing the government and that they planned to follow in the footsteps of Egyptians and overthrow the government in Tunisia.

An interim government, elected with the primary purpose of writing a constitution, has overreached its mandate by more than nine months, and has struggled to reconcile Tunisians' differing visions for the future of the country in draft versions of the constitution, prompting frequent demonstrations.

However, Ms Weslaty was sceptical that anything similar to the Egyptian events could happen in Tunisia. "Ennahda were more intelligent in dealing with the opposition," she said.

The Islamist party rules in a troika with two of the country's secular political groupings, and made concessions on issues like the role of Sharia in the constitution. Even when faced this year with their gravest crisis - the assassination of an opposition activist, which led to the resignation of the prime minister, Hamadi Jebali - calls by opposition leaders for the fall of the government did not have wide support.

Plans for a demonstration outside the Egyptian embassy yesterday morning were heeded only by a few people condemning the actions of the military. Ennahda's leader, Rached Ghannouchi, was quoted in Al Sharq Al Awsat newspaper yesterday as saying that although some Tunisians would attempt to recreate Egypt's events, he was confident they would be a minority.

Tunisia's president, Moncef Marzouki, ruled out the risk of Tunisia's elected authorities being deposed "because here the army is republican," he said, adding that Tunisia's leaders had to "understand this signal, pay attention, realise that there are serious economic and social demands".

In Libya, where the Muslim Brotherhood is one of a number of parties that have vied for political domination of the chaotic country, the move was eyed with deep suspicion by Islamist politicians.

"The Muslim Brotherhood may have made a lot of mistakes, because they are human, but they should be dealt with in a democratic way, not with the army," said Omar Sallak, a Brotherhood member and local politician form the eastern city of Benghazi. "They should understand that they cannot make it by themselves in Egypt. Now they are making a coup."

And yet, the fall of Mr Morsi's government was undoubtedly a blow for the organised, moderate Islamist parties in the region who have seen the success of Egypt's long-underground movement as a triumph.

In Turkey, where the Justice and Development Party has been a model for parties linked to the Muslim Brotherhood across the region, the foreign minister called the actions of the military "unacceptable".

"We have strongly supported the January 25 revolution of our fellow Egyptian friends," Ahmet Davotoglu said. "It is extremely worrying that Morsi, a president who was elected democratically, was ousted by the army."

Among the pro-democracy activists of other countries, the events were a sobering shadow over their dreams for the future. Syrian activists have struggled against the rule of Bashar Al Assad for more than two years and have watched the rise of armed extremist groups in their midst.

For them, the events prompted feelings somewhere between fear and jealousy, said Shakeeb Al Jabri, an activist based in Beirut.

"When we saw that many people out on the streets, and no one attacking them," he said, "this evoked envy among the Syrians and this is universal. The next day with the military statement and two days later with the coup - it was very different."

However, many Syrian activists, especially secular-minded ones, had no love for Mr Morsi. The events made them look ahead to a time - if Assad falls - when they fear a fiercely Islamist group might hold sway in Syria.

"In Syria, they are going to be the powerful ones with the weapons, so how the hell are we going to remove them if they become dictatorial?" said Mr Al Jabri. "But it's making Syrians think about important things, which is good."

afordham@thenational.ae

twitter: For breaking news from the Gulf, the Middle East and around the globe follow The National World. Follow us

Arab Spring countries question if Morsi's fall is end of an era

All eyes have been glued on Tahrir Square from Arab Spring countries, where Morsi's overthrow can be seen as a death sentence for a dream of regional democracy or the beginning of a second round of rebirths.

More from the national