BEIRUT // When Sebastian Stricker realised that smartphone users outnumbered hungry children in the world by 20 to one, he had an idea: to take the fight against malnutrition and poverty to the devices that most of us carry in our pockets every day.

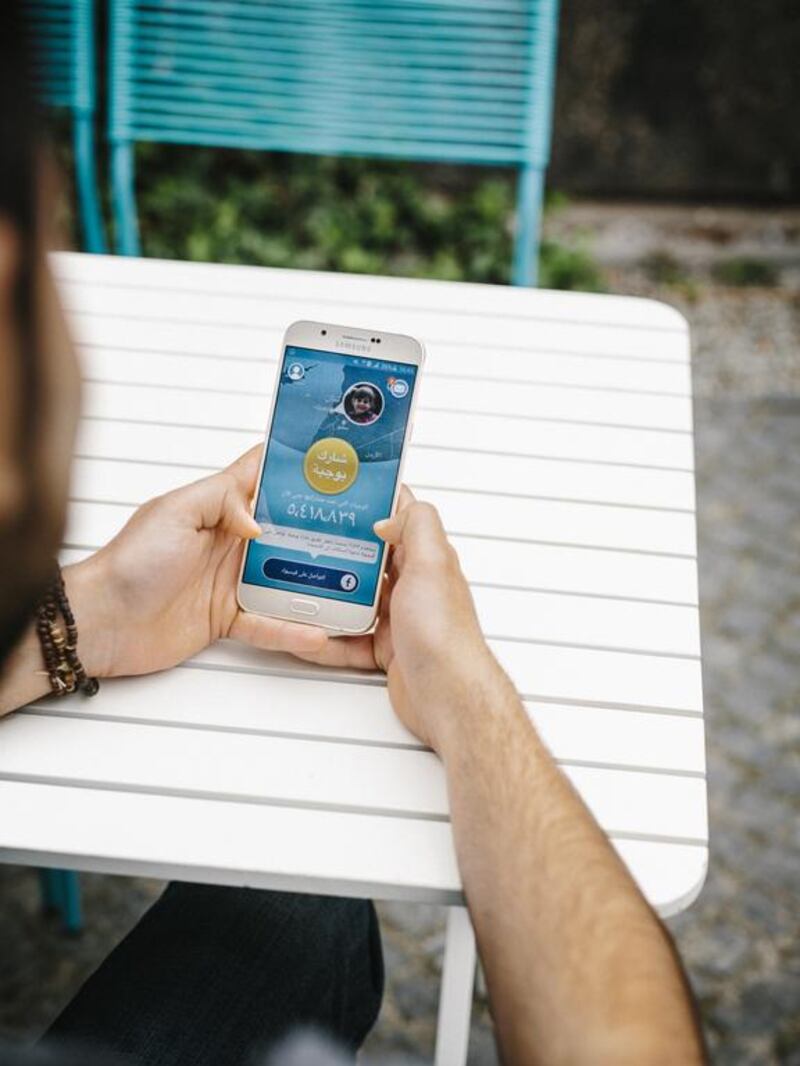

The result was the World Food Programme’s ShareTheMeal app, a crowdfunding programme that allows users to buy meals for children affected by war and poverty with the tap of a finger. Saying that it costs just Dh2 on average to feed a child for a day, the app encourages donors to take out their phones every so often while having a meal to donate to those who do not have enough to eat.

ShareTheMeal launched a trial run in German-speaking countries in June last year and was released worldwide in November. So far, more than half a million people have downloaded the app, purchasing more than six million meals.

Now, just in time for the giving spirit of the holy month of Ramadan, the app has launched an Arabic version to reach more users in the Middle East.

The app raises money for a specific group of children at a time, with the size of the group determined by how many children in that particular location, age range or category are considered “in need”. So far, ShareTheMeal has helped to feed 2,000 pregnant and nursing mothers and their babies in the Syrian city of Homs for a year, 20,000 Syrian children in Jordanian refugee camps for a year, and provided 1.8 million meals for schoolchildren in Lesotho.

Currently, money donated through the app is going to feed 1,400 Syrian children between the ages of three and four in Beirut. As of Saturday afternoon, the app had raised about 75 per cent of the funds required to feed the children for one year.

“You eat, and then maybe you then think ‘I have an app and if I press the button, somebody else can eat as well,” said Mr Stricker, ShareTheMeal’s developer and founder. “That is really the core idea.”

Since the start of Ramadan, the app – including both the pre-existing and Arabic versions – has already donated nearly a quarter of a million meals. Mr Stricker said the past week, the first of the month of Ramadan, has been the most successful so far in 2016.

“The beauty of ShareTheMeal is that you’re contributing in a very simple, practical and modern way,” said Dominik Heinrich, the World Food Programme (WFP)’s Lebanon director.

Funding refugees in Lebanon is an uphill battle.

Since March, the WFP has provided food vouchers worth US$27 (Dh99) per month to 700,000 Syrian refugees in Lebanon – roughly half of the estimated Syrian refugee population in the country.

The WFP says $27 is enough for a person to feed themselves nutritiously for a month. But many refugees still complain it is not enough. And as the aid only goes to refugees determined to be the “most vulnerable”, based on which refugees experience the biggest gaps in food consumption and their ability to obtain food, there are many others in extremely dire circumstances who receive nothing.

Current levels of food aid being distributed to Syrian refugees in Lebanon are double what they were last Ramadan when, amid budget shortfalls, the WFP cut the value of monthly vouchers to $13.50. This came after food aid had already been slashed from $27 to $19 in January last year.

Aid agencies are locked in a constant battle to find enough money to feed refugees.

“What we know is that overall, unfortunately, there is not enough money,” said Mr Stricker, referring to cash shortfalls among aid agencies. “If we (ShareTheMeal) weren’t there, for certain somebody wouldn’t be getting food.”

But lacking money for food does not simply mean refugees go hungry: the knock-on effects land them in cycles of poverty, debt, malnutrition and child labour.

When refugee families do not have enough money to make ends meet, they come under increasing pressure to pull their children from school and put them to work. Less than a third of Syrian refugee children in Lebanon were enrolled in formal education programmes this year. Today it is common to see children working in Lebanon, doing everything from tending to crops in fields to carrying heavy loads, making food in restaurants and begging on the street.

When refugees do not have money for even the basics, they also rack up debt from shopkeepers, landlords and wealthier family members. As a result of rent, food, health care and school payments in an economy where the few jobs going for Syrians are low paying, more than 90 per cent of Syrian refugees in Lebanon are in debt according to the United Nations. Syrian refugee families now owe an average of $940.

“Food is the most important ... expenditure a refugee has,” said Mr Heinrich. “You and I spend a [relatively small] amount of our expenditures on food ... your normal day-to-day living, your food bill is what, 10 per cent? For a refugee it becomes 50 per cent.”

“So if you don’t support the food security and the nutritional aspect, then you also have an impact on health, education [and shelter].”

jwood@thenational.ae