NAIROBI // From the air, the refugee camps on Kenya's dusty north-eastern plain resemble a densely packed city with plots laid out neatly on a grid, with roads intersecting neighbourhoods. On the ground, these camps along the Somali border, which have housed refugees for 18 years, seem more like a permanent municipality than a temporary settlement. There are markets, mosques and schools as well as an internet cafe. But to the young Somalis, many of whom have lived most of their lives in the sprawling Dadaab refugee complex, the camps are more like a prison than a home. Kenyan authorities have illegally forced refugees to stay in the squalid and cramped camps by restricting their movement throughout the rest of the country, Human Rights Watch said in a report last week. Kenyan police have also abused refugees and illegally deported them back to Somalia, which is embroiled in civil war, the leading rights watchdog said. "People escaping violence in Somalia need protection and help, but instead face more danger, abuse and deprivation," Gerry Simpson, a refugee researcher at Human Rights Watch and author of the report, said. "Somali asylum seekers should be able to cross the border safely and get the aid in Kenya they urgently need." The three camps in the Dadaab complex are now overflowing with 260,000 people, making it the largest refugee settlement in the world. Officially, no new arrivals are supposed to be allowed in, but 20,000 new refugees crammed into the camps in the first two months of this year and another 220 are streaming across the border each day, according to the United Nations High Commission on Refugees. The new arrivals are forced to squat on other refugees' plots and have added to the deteriorating humanitarian situation. "The status of land is key," Mr Simpson said. "We are facing a crisis in Dadaab on finding new land." Somalia's civil war, which started in 1991, ramped up in 2007 when Ethiopian troops entered Somalia to oust an Islamic government. The Islamists started an insurgency that has killed thousands and has forced tens of thousands to flee to Kenya. Kenya officially closed its border with Somalia in Jan 2007, blaming security concerns. Still, asylum seekers have managed to cross the porous frontier, braving hardships and abuse along the way. The closed border goes against international laws governing refugees and makes it more dangerous for those trying to cross, Mr Simpson said. "Kenya has been in flagrant violation of its obligation to Somalis freely seeking asylum," he said. "The border closure has only made Somali refugees more vulnerable to abuse and lessened the government's control over who enters Kenya and who is registered in the camps." In the report, From Horror to Hopelessness, Human Rights Watch details abuses by Kenyan police officers along the border. Officers detain, beat and extort bribes from asylum seekers. Those who cannot pay are sent back to Somalia. Some women have been raped by Kenyan police, according to the report. A police spokesman said the department was investigating alleged abuses within its ranks. A police statement called the report, "a deliberate falsehood concocted to discredit government efforts and depict Kenya as hostile to Somali refugees". The refugees who manage to cross the border and make it to the camps are not allowed to leave without a special travel permit. Many still migrate to the Somali slums in Nairobi and some are arrested and sent back if they are caught outside the camps without a permit. The overcrowding in the camps has created a humanitarian disaster. Oxfam, the British aid organisation, said in a separate report last week that many people in the camp lacked access to basic necessities such as food and water. "Conditions in Dadaab are dire and need immediate attention," Philippa Crosland-Taylor, the head of Oxfam Great Britain in Kenya, said. "People are not getting the aid they are entitled to. Half of the people in the camp do not have access to enough water. Women and children, who make up over half of Dadaab's population, very rarely have access to adequate latrines." As the new Somali government continues to wage war with Islamic militants, the camps continue to grow. The United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) said the camps could be holding as many as 360,000 by the end of the year. Aid organisations and human rights groups have repeatedly asked the Kenyan government to allocate more land for the refugees. In February, the government agreed to allocate land for 50,000 refugees, which would help ease overcrowding, but would not be enough to accommodate the expected new arrivals this year. UNHCR has appealed to the international community for US$92 million (Dh338m) to help stem the humanitarian crisis in the camps. Donor nations so far have failed to respond to the appeal. "At the moment it's like pulling teeth," Mr Simpson said. "Donors aren't increasing their funding and it seems they're waiting for a fresh crisis to break out." mbrown@thenational.ae

When freedom is more like a prison

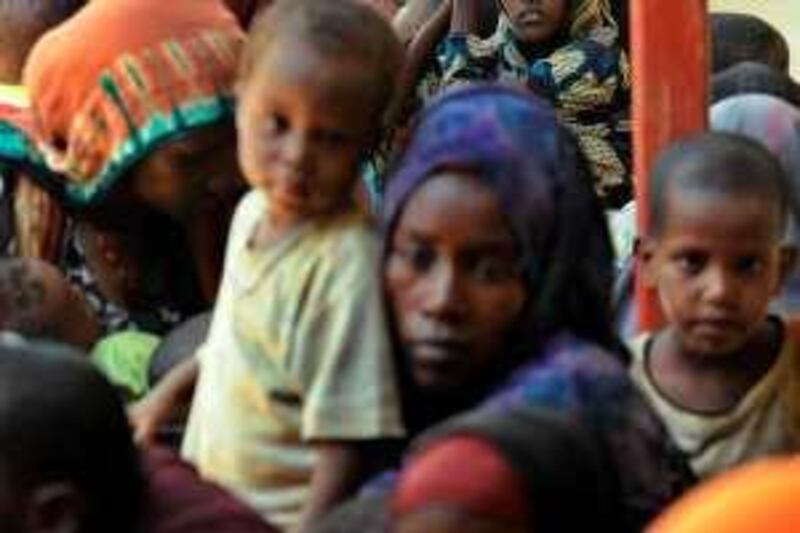

Somali refugees camps in Kenya are reaching a crisis point, overflowing with more than 260,000 people and hundreds of new arrivals every day

More from the national