CASABLANCA // Tong Wei is not sure why, 18 years after leaving his native China, he still smokes Lesser Panda cigarettes. "Maybe just because everyone back home smokes them," mused Mr Tong, 30, a leather goods merchant in central Casablanca. "But that's not to say I miss China." Mr Tong is happy right where he is, comfortably established since 2003 in the Casablanca mercantile quarter of Derb Omar, part of a wave of Chinese traders and companies that have flooded Africa in recent years.

African consumers have eagerly snapped up cut-rate Chinese goods and services. But some also grumble that China is profiting at the expense of African jobs, while forays into North Africa are helping to complicate China's relationship with the Muslim world as it clamps down on a disenfranchised Muslim minority. The spectre of North African terrorism appeared two weeks ago when Stirling Assynt, a British risk assessment firm, said it had evidence that Algerian militants affiliated with al Qa'eda were urging attacks on Chinese in the region in response to clashes this month between police and Muslim Uighurs in China's Xinjiang province that have killed around 200 and injured over 1,700.

While it is unclear how the violence started, some Muslims from outside China have condemned what they consider an attack by the Chinese government on their co-religionists. Algeria's Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat arose during the civil war of the 1990s, and in 2007 re-branded itself al Qa'eda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). While it primarily targets the Algerian state, the group has also killed and kidnapped foreigners.

In May, AQIM executed a British hostage, Edwin Dyer, after the UK refused the group's demand that the Jordanian al Qa'eda leader Abu Qatada be released from a British prison. Attacks on Chinese people or businesses have yet to materialise, but unrest in Xinjiang coupled with the reported AQIM threat have prompted China to warn its citizens abroad and work with local authorities to tighten security for Chinese interests.

About 30,000 Chinese are currently in Algeria, where the government has awarded numerous building and oil contracts to Chinese firms. Neighbouring Morocco represents a frontier of China's commercial expansion, with at most 2,000 Chinese expatriates, according to the Chinese embassy in Rabat. "China sees Africa as a virgin continent," said Tajeddine El Houssaini, an economics professor at Mohammed V University, in Rabat. "This new Chinese presence is part of a strategy to compete with the US and Europe."

In 2006, the Chinese president, Hu Jintao, made a deal-signing tour of Africa, and China earmarked US$5 billion (Dh18b) to help Chinese companies gain a foothold in the continent. Between 2007 and 2008, trade between China and Africa nearly doubled to almost $107bn. Meanwhile, African shoppers have been bathing in a flood of cheap household goods imported from China. In Morocco, Chinese merchants in Derb Omar have become notorious for consistently undercutting their local competitors.

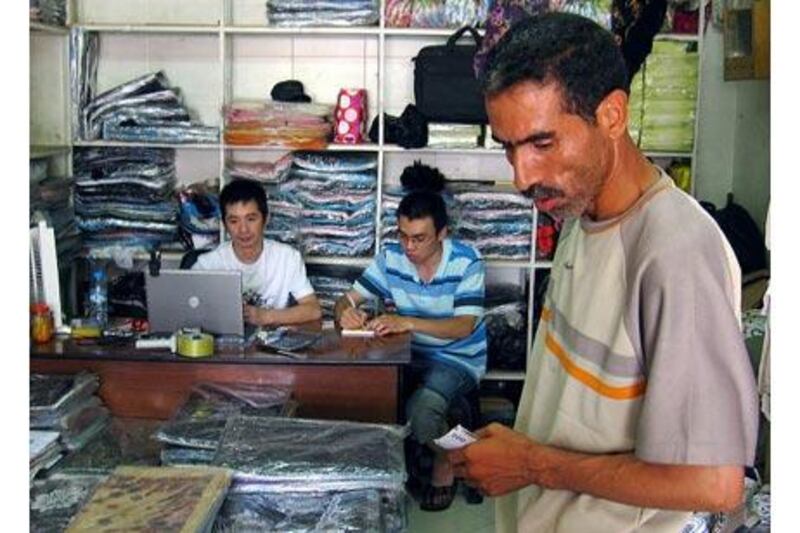

The streets around Tong Wei's shop are clogged with vans, pushcarts, and Moroccan labourers bellowing at one another as they unload made-in-China merchandise. Chinese faces gaze impassively from doorways. At lunchtime, the merchants sit outside eating stir-fry from ceramic bowls. "My family have always been traders," said Mr Tong, lighting up a Lesser Panda. His wife Lin, 25, sat beside him on a stool, eating rice with vegetables.

When he was 12 years old, Mr Tong and his family left their home in the coastal province of Fujian and settled in Moscow. Six years ago they moved to Casablanca, where today Mr Tong and his wife sell women's handbags. The couple declined to say how much money they made but their earnings allow them to live comfortably and travel periodically to China, where their two young children are staying with Mr Tong's parents to attend school.

"In Russia the police always gave us trouble," Mr Tong said. "We're better off here in Morocco. As long as business is good, we're staying." At a Chinese-run shoe shop nearby, a Moroccan sales clerk named Khadija Azli, 25, is less sanguine. Six months ago, global financial turmoil snuffed out Ms Azli's job with a multinational electronics company. She found low-paying work in Derb Omar, where Chinese merchants unable to speak much Arabic or French hire Moroccan assistants.

"The Chinese are colonising us in a way," Ms Azli said, removing a gold plastic slipper from its box. "For example, this is a Moroccan model. What the Chinese do is they take something like this to China, copy it cheaply, then sell the copy back here." Business executive Lin Xiao takes a different view of his company's place in Morocco. "Our role is to be like a citizen," said Mr Lin, who heads Morocco operations for Huawei, a Chinese telecommunications giant.

Since opening in 1999, his office has grown from a handful of Chinese engineers to some 200 employees, 60 per cent of them Moroccan, and now offers training and internship programmes as well. "We're not just here to make quick money," Mr Lin said. "Our strategy is long term." jthorne@thenational.ae