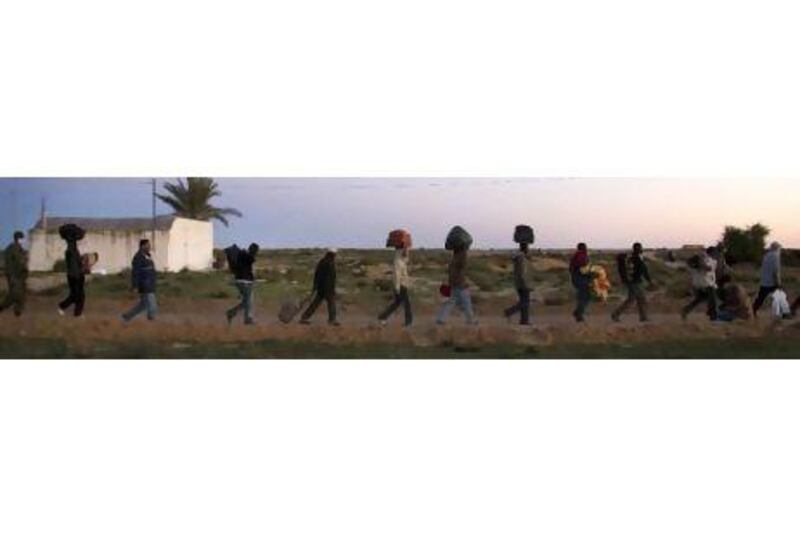

RAS AJDIR, Tunisia // The whistle-blasts of the Tunisian soldiers ripped through the air, and Mounir Hussain mechanically walked forward with hundreds of fellow refugees.

Nearby, more refugees from Libya's violence were being ushered into the country by Tunisian border guards and workers from the International Organisation for Migration, a UN agency helping organise the refugees' repatriation.

"What will I say to my family when I come home with nothing?" said Mr Hussain, 26, a Bangladeshi labourer who fled Libya last week amid the revolt against Muammar Qaddafi.

About 90,000 mostly foreign workers have passed through the Tunisian border post at Ras Ajdir. Thousands also appear stranded near the border, growing increasingly desperate.

Pressure on the border, however, began easing yesterday as countries stepped up repatriation flights.

Mr Hussain's journey to Ras Ajdir began 15 months ago in Bangladesh, when rural poverty drove him abroad.

"People said you could find work in Libya, and I couldn't get a visa to other countries," said Mr Hussain, who paid a broker US$7,500 (Dh27,500) to obtain a Libyan visa for him.

Libya has liberalised its economy and spent part of its oil wealth on badly needed infrastructure since international sanctions were lifted in 2003, luring foreign companies and workers.

After five months without work and six weeks with a Libyan building company that paid only in food, Mr Hussain found a job installing air ducts for a Maltese firm in Tripoli. "I was happy, because at last I had money to send home to my family," he said.

Mr Hussain's success swiftly collapsed after February 21, he said, when Col Qaddafi's son, Saif al Islam Qaddafi, told Libyans in a televised address to unite against foreigners he blamed for violence in the country.

Later that day, Libyan forces opened fire on protesters in Tripoli calling for Col Qaddafi to depart after 41 years in power.

Mr Hussain's manager informed the firm's 40 Bangladeshi workers that the operations were ceasing. A Chinese engineering company employee named Liu Yu Tong also recalled hearing of Saif's speech with trepidation in Tripoli's suburb of Tajoura. By the end of day, the company's four Libyan drivers had quit their jobs, leaving the Chinese engineers and other workers hunkered down in their office.

The next day, a Libyan friend of Mr Liu who managed a small state engineering agency told them by telephone that armed men - apparently bandits - had robbed the office three times that day, stealing cars and computers and sexually assaulting two women employees.

"After that the phones were cut, shops closed and there was no water or electricity," said Mr Liu, a translator from Hunan province. The next morning Mr Liu and his colleagues set out by car for the Tunisian border.

"There were soldiers on the road who stole our mobile phones and memory cards," said Mr Liu, echoing a common complaint among refugees from Libya.

On February 24, Mr Liu entered Tunisia with about 190 Chinese employees of his firm, accompanied by Chinese diplomats. That evening they were given rooms in an upscale hotel in Zarzis, a seaside resort town, and last week were waiting to be sent home by the Chinese government.

Meanwhile, Mr Hussain said he and his colleagues hid out for three days in their Tripoli office after the violence started, listening to gunfire outside every night.

Mr Hussain telephoned his parents, who urged him to flee. Last Monday he arranged bus transport to Tunisia, borrowing money when the driver raised the price at the last minute.

Like Mr Liu, the Bangladeshis were robbed of their mobile phones and memory cards at checkpoints manned by Libyan forces, Mr Hussain said. They reached the border on Monday night.

The group huddled on the bare ground, trying to sleep through the cold, rain and wind. Mr Hussain asked a guard on the Libyan side of the border if they could join other refugees sleeping indoors.

"It's forbidden," said the guard. "We're getting sick," Mr Hussain said. "Please." "Impossible," the guard replied.

On Tuesday the group were pressed into no-man's land between the two countries, which was teeming with thousands of refugees. That night they were allowed to sleep indoors, and on Wednesday morning entered Tunisia, their future uncertain.

UN agencies and Tunisian authorities and volunteers have stepped into the gap left by some governments struggling to mount repatriation missions.

When the first refugees reached Ras Ajdir on February 19, a retired Tunisian soldier named Abdeslam Hamad leapt into action, helping organise transport, food and housing at municipal buildings in the nearby town of Ben Guerdane.

"I've been here 24 hours a day, always running," said Mr Hamad, who met yesterday with volunteers, Tunisian army officers and UN staff at Ben Guerdane's cultural centre. "One minute on the phone, the next out among refugees."

Initially, refugees were ferried by bus and car to the cultural centre for a meal donated by local restaurants, before being lodged in schools, community centres and youth hostels. Today accommodation near the border is concentrated at a tent city run by the Tunisian army, the Red Crescent and the UN's High Commission for Refugees, where thousands are awaiting repatriation by plane and boat.

While scenes of chaos at the border early this week have been replaced by orderly queues, UN officials stress the urgent need for more transport to prevent a humanitarian crisis.

Yesterday, Eric Laroche, the assistant director general of the World Health Organisation, said that the concentration of people at Ras Ajdir contained "all the ingredients for an epidemic explosion".

On Wednesday afternoon, Mr Hussain and his companions were on the border, awaiting transport to the tent city several kilometres away. "At this moment, I don't know what will happen to me," said Mr Hussain, choking back a tremor in his voice. "I have to do something for my family, but I lost everything in Libya. How am I going to get home?"