The Sudanese authorities are blocking access to social media used to organise nationwide anti-government protests triggered by an economic crisis.

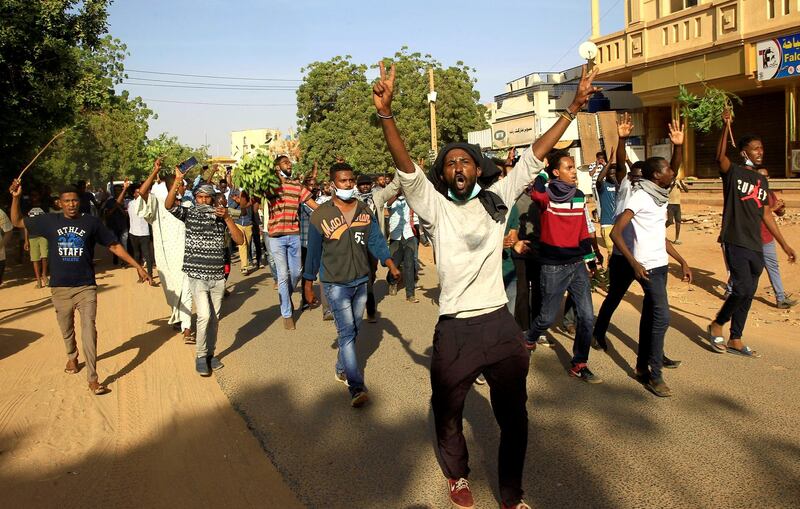

Sudan has been rocked by near-daily demonstrations in the past two weeks.

Protesters burnt ruling party buildings and called on President Omar Al Bashir, who took power in 1989, to stand aside.

In a country where the state controls traditional media, the internet has become an important information battleground. Of Sudan’s 40 million people, about 13 million use the internet and more than 28 million own mobile phones.

The authorities have not repeated the internet blackout imposed during deadly protests in 2013. But the head of Sudanese intelligence, Salah Abdallah, said last month that there was “a discussion in the government about blocking social media sites and in the end it was decided to block them”.

_______________

Read more:

Chaos in Khartoum as Sudanese forces break up protest against Omar Al Bashir

Persistent protests testify to deep-rooted anger in Sudan

Sudanese activists vow not to back down against Bashir

_______________

Users of the three main telecoms operators in the country – Zain, MTN and Sudani – said access to Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp has been possible only through use of a virtual private network.

Although VPNs can bring their own connection problems and some Sudanese are unaware of their existence, activists have used them widely to organise and document the demonstrations.

Hashtags in Arabic such as “Sudan’s_cities_revolt” have been widely circulated from Sudan and abroad. Hashtags in English such as #SudanRevolts have also been used.

“Social media has a really big impact, and it helps with forming public opinion and transmitting what’s happening in Sudan to the outside,” said Mujtaba Musa, a Sudanese Twitter user with more than 50,000 followers.

The situation in Sudan has now directly effected my family. My first cousin Tarig Salah was brutally beaten by oppressive forces.

— SINKANE (@Sinkane) January 2, 2019

GET FAMILIAR WITH THE SITUATION IN SUDAN. Follow these hashtags and tell your friends and family.

#sudanrevolts #sudanuprising #مدن_السودان_تنتفض pic.twitter.com/aJWlyfgyBw

NetBlocks, a digital rights NGO, said data it collected – including from thousands of Sudanese volunteers, provided evidence of “an extensive internet censorship regime”.

Bader Al Kharafi, chief executive of Zain Group, said: “Some websites may be blocked for technical reasons beyond the company’s specialisation.”

Neither the National Telecommunications Corporation, which oversees the sector in Sudan, nor MTN or Sudani could be reached for comment. Twitter and Facebook, which also owns WhatsApp, declined to comment.

“While Sudan has a long history of systematically censoring print and broadcast media, online media has been relatively untouched despite its exponential growth ... in recent years,” Mai Truong of US-based Freedom House said. “The authorities have only now started to follow the playbook of other authoritarian governments.”