Sudan’s perennial struggle with its identity has been at the root of the Arab-Afro nation’s tragic record of civil wars that have killed hundreds of thousands of people, displaced millions and devastated the economy.

Sudan gained independence in 1956 but often appeared to be on the brink of disintegration, with several conflicts raging at once.

Invariably, the violence had ethnic or religious undertones.

Agreements reached recently in Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, and Juba in South Sudan, between Sudan’s transitional government and two rebel outfits offer a glimpse of hope that Sudan could at last be unified.

But analysts and activists say that there are still daunting challenges ahead and the concessions Khartoum must offer to secure lasting peace could prove politically costly.

Sudan’s woes deepened during dictator Omar Al Bashir’s 29-year rule, which ended last year when his generals removed him from power.

That followed months of protests by pro-democracy activists striving for the elusive goal of a new Sudan, where citizenship supersedes ethnicity or religious affiliation.

It is a tall order in a country where religious piety and conservatism are defining traits and an Arabised group has held political and economic power since 1956.

Changes require a major overhaul of the country’s political landscape that Sudan’s transitional government may not be able or willing to carry out.

The steps required to bring peace to Sudan after years of civil war in the west and south of the country could also spark resistance from groups with economic interests, Islamists and supporters of powerful traditional political parties, such as the National Umma Party of former prime minister Sadiq Al Mahdi.

Its followers, like generations before them, have a sense of ethnic and cultural superiority over the people living in Sudan’s western and southern regions.

Sudan’s leaders are adamant that change is essential if the country were to introduce democratic rule and prevent more division.

The mainly Christian and animist south seceded in 2011 after a civil war that ran between 1983 and 2005.

Peace is also desperately needed to reduce the government’s huge defence spending, which is about half of the national budget, and fund public services and overhaul collapsing infrastructure.

Peace is also required to secure the resumption of aid by western donors who are unhappy about reports of widespread human rights breaches in conflicts in the west and south of the country.

But questions have also been raised about whether Sudan’s leadership has a genuine desire to make those changes or is qualified to conduct negotiations in a way that would resolve core problems.

There are concerns that the government may simply offer rebel groups political bribes as part of shaky agreements, the likes of which failed to secure peace in the past or led to the rise of new rebel groups.

But Sudan has already taken steps, albeit mostly symbolic or of limited scope, towards realising the elusive dream of equality for all as a prelude to a lasting peace.

Last week, the government signed a peace deal with a coalition of rebel groups that barely has a military presence.

To some, details of the deal mirrored the bribes Al Bashir and another Sudanese dictator, Jaafar Nimeiri, who ruled between 1969 and 1985, gave southern rebel leaders in exchange for agreeing to peace deals that were either ineffective or eventually unravelled.

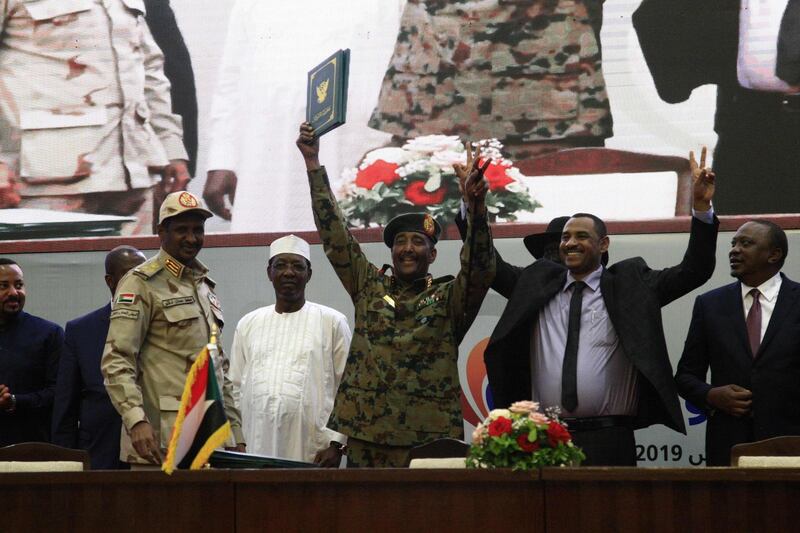

The government promised the Sudan Revolutionary Front three seats on the Sovereignty Council, which has acted as a collective head of state since a power-sharing deal between the military and pro-democracy groups was reached last August.

It also offered the rebels five ministerial posts and 75 of the 300 seats in a new transitional parliament.

The deal said rebels would be integrated into the armed forces and compensation would be offered to residents forced to leave their homes because of the fighting.

Those who lost land to the government or allied militias are also to be compensated.

“The success of this agreement depends on the seriousness of both sides in implementing the terms and refraining from embracing narrow and self-serving interpretations,” said Attiya Issawi, an Egyptian analyst.

“The incorporation of rebels in the ranks of the armed forces could be the trickiest one given the likely friction between former enemies when they serve together."

This week, the government said the separation of state and religion would be the basis of a future constitution.

It made the announcement in a joint declaration with the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North, a major rebel group active in the west and south.

The group refused to take part in the peace process last month.

Sudanese media celebrated the declaration as a political milestone, but activists and analysts consider it to be no more than a show of mutual good will as the two sides begin new peace talks.

Analysts also raised doubts about the sincerity of the rebel group as it begins negotiations given that its desire for secession is the heart of its ideology.

The group, led by Abdel Aziz Al Hilu, has a stronghold in the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan, which has a significant Christian community among its mainly non-Arab population.

The area has been the main battlefield in a conflict that broke out in 2011.

Mr Al Hilu has long supported the introduction of a secular state to replace Al Bashir’s government.

Amany Al Taweel, a Sudan expert from Egypt’s Al Ahram Centre for Political and Strategic Studies, said Mr Al Hilu could be open to supporting secularism instead of the right to self-determination.

“The separation of religion and state is a historical demand in Sudan and is key to the ‘margin’ regions of the south and west, where it is seen as the appropriate response to the country’s diversity," Ms Al Taweel said.

"It is not a demand that is in isolation of the political history of Sudan."

She said that while such a system was uncommon in most Muslim-majority countries, it was generally accepted in Sudan.

“Thirty years of Al Bashir’s rule have shown the Sudanese that bringing religion into the affairs of the state could bring about the collapse of the nation,” Ms Al Taweel said.

Since taking power, the transitional government took several small steps towards dismantling Al Bashir’s legacy and winning back some of the international respect Sudan lost during his rule.

The government banned female genital mutilation, a common practice in the country, repealed a law regulating what women could wear in public and said people guilty of apostasy could no longer be sentenced to death.

The government agreed in principle to hand Al Bashir to the International Criminal Court to face charges of crimes against humanity and genocide during the civil war in Darfur.

The UN said 300,000 people were killed during the conflict, which began in 2003 and displaced more than two million.

Al Bashir has been in jail in Khartoum since he was removed from power.

"Peace in Sudan remains a distant goal," said Rasha Awad, a Sudanese analyst and editor of online news outlet Altaghyeer.

"The core issues such as the relation between the state and religion have not been resolved."

The transitional government has yet to wholeheartedly move to dismantle Al Bashir’s divisive legacy, Awad said.