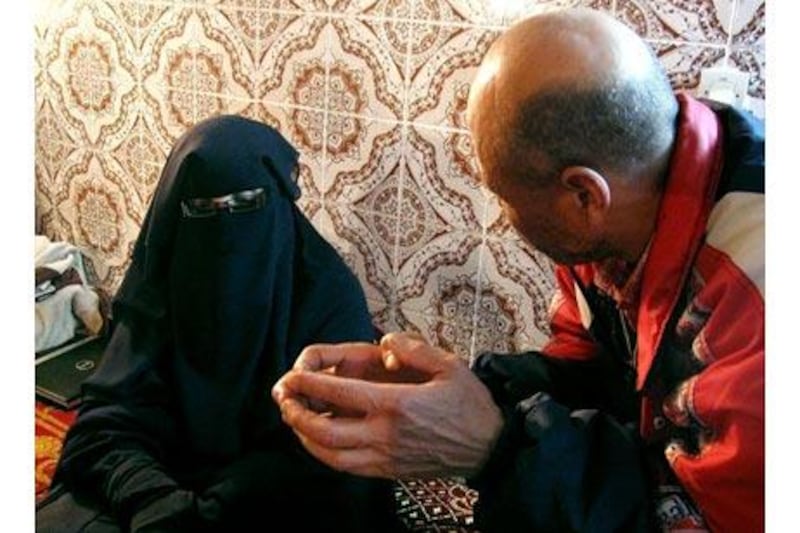

RABAT // Fatiha Hassani's lawyer had been talking for under a minute when the judge made a rumbling noise, then abruptly cut him off. "That's enough!" the judge said. "Your case has no grounds. Verdict next month." Ms Hassani, her lawyer and a small crowd of supporters filed out of the courtroom and into a winter morning in Rabat, the Moroccan capital, defeated but defiant. The hearing in January was over a demand for reparations by Ms Hassani, a vocal supporter of al Qa'eda, from a government she says unlawfully imprisoned her and her son during anti-terrorism clampdowns after suicide attacks in Casablanca in 2003.

While Moroccan officials are now fighting terrorism more effectively, with better intelligence and fewer arrests, lawyers and human rights groups say innocent people remain in prison, some terrorist suspects are being tortured and many trials are unfair. Ms Hassani has become a fixture in Moroccan media, tall and outspoken beneath the black gown and face veil she considers it her Islamic duty to wear.

She once studied law and left her hair uncovered. Then the spectacle of US bombs falling on Iraq during the 1990 Gulf War drove her towards religion. "I had admired the West, but it was like the dream of a little girl," said Ms Hassani. She turned instead to the Quran. "I started doing my prayers and wearing a hijab." In 2001, she left Morocco with her husband, Karim el Mejjati, and their two sons for Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, "the most wonderful period in my life".

It proved brief. The US-led ousting of the Taliban in 2001 inspired Mr el Mejjati to join al Qa'eda before the family fled into exile, settling in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia by 2003. A trip to the eye doctor in March 2003 became a nightmare when Ms Hassani and her elder son, Elias, were snatched by Saudi plainclothes agents, she said. Mr el Mejjati and the couple's younger son, Adam, were killed during gunfight in 2005 with Saudi forces.

Meanwhile in Morocco, a violent strain of Salafi Islam was gaining ground in the slums encircling major cities. In May 2003 it exploded into Morocco's consciousness with suicide attacks in Casablanca that killed 12 bombers and 33 civilians. The attacks caught authorities by surprise, said Mohamed Darif, a professor at Morocco's Mohammedia University and an expert on political Islam. "To contain the threat, they arrested everyone known for Salafi tendencies."

"Many people who attended mosque at fajr were arrested, since it's the earliest prayer and only true Muslims do it," said Fatima-Zohra Koutaibi, whose son Rafik Adnane was jailed for 20 years in 2003 on charges of having helped to kill a policeman in 1999. "The police came to the house at 6.30 in the morning and waited until he returned from praying." Mrs Koutaibi said her son, although deeply religious, had never been mixed up in violent extremism and was innocent of the charges against him.

As security forces went into overdrive, thousands were arrested under sweeping new antiterrorism laws as the country became an integral part of US and European antiterrorism campaigns. In June 2003, Ms Hassani said, Saudi authorities delivered her and Elias, then aged 10, to Morocco, where they were held for nine months at an alleged secret detention centre at Temara, near Rabat, before being released.

Moroccan authorities deny that Ms Hassani and her son were detained and have not acknowledged the existence of the alleged Temara detention facility. Police have worked more adroitly since the former security chief Hamidou Laanigri, the architect of antiterrorism sweeps that human rights groups say sent many innocents to jail, was fired in 2006, said Mr Darif. While terrorism remains a threat, Morocco relies increasingly on technology and co-ordination with neighbours to make fewer, more targeted arrests, he said.

About 1,000 people are currently in prison on terrorism charges, said Abderrahim Mouhtad, the president of An Naseer, a human rights group that is calling for fair treatment of Salafi detainees. Justice ministry officials could not be reached for comment. Both arrests and the length of sentences have decreased, said Taoufik Mousaif, a lawyer in Rabat who defends many terrorist suspects. But many of Mr Mousaif's clients say they have been beaten, deprived of sleep and denied access to a lawyer during police investigations, he said.

Such claims are easy to make but hard to verify, said Khalid Naciri, the communication minister. "People have the right to claim they've been tortured, but they must present proof that this is the case." While there have been rare cases of abuse by authorities, these have been made public and offending officials held accountable under Moroccan law, which forbids torture, Mr Naciri said. In January, King Mohamed VI named a new justice minister, a move widely seen as geared towards judicial reform that the king has made a top priority.

Ms Hassani says courts have so far denied her a fair hearing. She has petitioned Morocco's government three times to recover the bodies of her late husband and son from Saudi Arabia, without success. Now she wants the state to cover medical bills for Elias who is suffering from depression and eating disorders that she says has resulted from his alleged solitary confinement. "Even if I were the greatest criminal in the world, would that excuse the kidnap and torture of a child?" she said.

Last month the court in Rabat ruled against her. She is planning to appeal. jthorne@thenational.ae