In an ignominious end to a political career lasting decades, Thabo Mbeki yesterday announced his resignation as president of South Africa, rejected and reviled by the party to which he has devoted his life. It is the final victory for Jacob Zuma, once a friend and fellow exile but now Mr Mbeki's greatest foe, in a titanic struggle for power that has split the African National Congress (ANC) and commanded the country's entire political attention for years.

It could herald wholesale change within the government of South Africa, the economic powerhouse of the continent, as many ministers are allies of Mr Mbeki - although the finance minister, Trevor Manuel, whose stewardship is regarded as key to the country's growth, is staying on. In the morning, Gwede Mantashe, the ANC's secretary general, announced that the party's national executive committee, its highest decision-making body, was sacking Mr Mbeki.

"After a long and difficult discussion, the ANC decided to recall the president before his term of office expires," he said. Technically the ANC has no explicit power to do so, but although Mr Mbeki, 66, was elected president by the people of South Africa, the country has a proportional representation system and the voters did so as a function of his position at the top of the ANC's parliamentary list.

The party has long had difficulty distinguishing between itself and the state, regarding all its members in government as "deployed cadres", sent there as its functionaries and subject to its discipline. A statement issued later by the presidency said formally: "Following the decision of the National Executive Committee of the African National Congress to recall President Thabo Mbeki, the president has obliged and will step down after all constitutional requirements have been met."

Parliament must now elect a successor from within its ranks in the next 30 days. Mr Zuma would have to be appointed to the legislature first, and it may be that an interim figure is appointed to the post. Baleka Mbete, the speaker of parliament, has been mooted as a possibility, while Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, the deputy president, has signalled she will resign along with her superior. It is perhaps Mr Mbeki's final favour to the organisation he joined at age 14, more than half a century ago, rising to power through the internecine plots of exile politics but finally brought down by his own faults and failings.

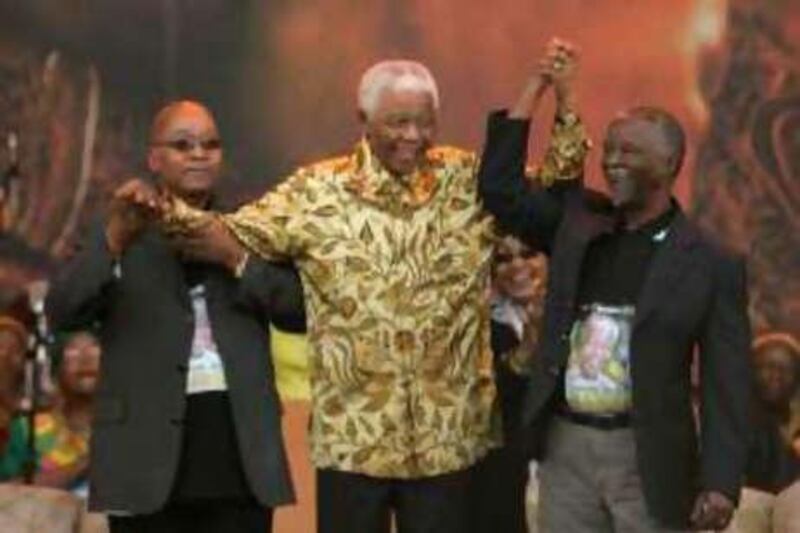

An intensely ambitious man, who was an extremely powerful deputy president to Nelson Mandela in South Africa's first democratic government, before taking over the top job in 1999, he saw plots and enemies around him many times, and while he marginalised and outmanoeuvred opponents real and imagined, the result was a growing swell of resentment against him among senior party figures. His aloof, intellectual manner - he is a staggeringly dull public speaker - only reinforced the impression of a man who considered himself above his fellows, as did his insistence, in the face of every accepted scientific principle, that Aids was caused by poverty rather than the human immunodeficiency virus. For years he obstructed the universal distribution of anti-retroviral drugs, even as 1,000 South Africans a day died from the disease. For his part, he insisted that he knew no victims of it.

Eventually the anti-Mbeki sentiment coalesced around Mr Zuma, 61, whom he had fired as his own deputy after Schabir Shaik, Mr Zuma's financial adviser, was convicted of soliciting bribes for him from a French arms company. Related charges against Mr Zuma were dropped but later revived, and he remains an intensely controversial figure, acquitted of raping a HIV-positive woman in 2006 during a trial in which he told the court he did not use a condom but showered afterwards as an Aids prevention measure, and whose campaign anthem Umshini Wami translates as "Bring Me My Machine Gun".

Last year Mr Zuma, who bases his populist appeal on sympathy for the poor seen as ignored by Mr Mbeki's pro-growth emphasis, stood for the leadership of the ANC and Mr Mbeki, having convinced himself that he was the only man who could stop him, sought a third term in the post. The result was a political massacre amid tumultuous scenes at the party congress in Polokwane, where Mr Zuma swept to victory and his allies took every single elected party post and a majority on the NEC.

Ever since, there have been two centres of power in South Africa, and severe tensions between them, with provincial premiers being dismissed amid faction-fighting and even instances of violence, but yesterday's final confrontation was only made possible by a judge. After Mr Zuma's corruption charges were revived, he went to court seeking a ruling that his rights had been violated. Amid bloodthirsty rhetoric from his allies, saying they were prepared to "kill for Zuma" and claiming a judicial conspiracy against him, the judge issued a decision that was devastating for Mr Mbeki.

Although he stressed that his ruling did not impinge on Mr Zuma's guilt or innocence, he dismissed the allegations, saying that they appeared to be politically motivated and the prosecution a "Kafkaesque" process. By implication, Mr Mbeki appears to have been ultimately responsible, and his enemies moved in for the kill. "This is not a punishment," Mr Mantashe, the ANC's secretary general, said yesterday. "We decided to take this decision in an effort to heal and reunite the ANC."

But that remains to be seen. Mr Mbeki still has his supporters, and Mr Zuma's allies are united by little more than their loathing for him - which will now need to find a new focus. The ANC will undoubtedly win the general election that is due within months, but the wounds of political assassination can fester for years. sberger@thenational.ae