CAIRO // Nearly 21 months after the fall of Hosni Mubarak, Egyptians are only beginning to grasp how riddled with corruption their country has become in the past three decades.

Much attention has been focused on the high-profile, Mubarak-era businessmen and politicians who have been convicted of bribery and cronyism. Their excesses and comeuppance are regular fodder in Egypt's media, their lives portrayed as seamy morality tales of the powerful brought low.

Little notice has been paid, however, to the less extortionate but far more prolific acts of graft and double-dealing that have spread like a noxious weed through everyday life in Egypt, drawing away the resources needed for a healthy economy to thrive.

Although the new government of president Mohammed Morsi has pledged to tackle corruption, it has been hobbled by the political ferment that has roiled Egypt since Mubarak was forced from power.

The Supreme Constitutional Court dissolved Parliament just a few months after it was voted in, so the government regulators and watchdogs assigned to root out corruption remain the problem more than the solution.

"Corruption has become common practice here in Egypt for governmental agencies," said Mohamed El Sawy, the chief executive of Misr Contracting Company and head of the Egypt Junior Business Association's anti-corruption group.

Mr El Sawy described how the proliferation of government regulation during the Mubarak years has given inordinate power to bureaucrats who have used their influence to create backdoors for companies willing to pay small bribes.

Combined with a huge public sector where wages are dismally low, it as an environment ripe for corruption.

Standing between the completion of a building or the delivery of a service is usually a local or federal government employee "adding complications in the promise to remove them if you bribe them one way or another", he said.

While anything but gentle to those Egyptians victimised by corruption, social scientists call Egypt a "soft state".

In such a system, the "state passes laws but does not enforce them", writes Galal Amin in his book Egypt in the Era of Hosni Mubarak, which was published last year.

Corruption becomes "a way of life", says the influential Egyptian political scientist, where "elites can afford to ignore the law because their power protects them from it, while others pay bribes to work round it".

"Everything is up for sale, be it building permits for illegal construction, licenses to import illicit goods, or underhand tax rebates and deferrals. The rules are made to be broken and to enrich those who break them, and taxes are often evaded."

Studies of Egypt's inflation rates point to another type of corruption that flourished during the Mubarak years.

Under his regime, monopolies and cartels were allowed to multiply and operate freely, despite laws and regulations that prohibit price-fixing and collusion to keep prices artificially high.

This price-dictating activity, the burden of which falls most heavily on ordinary Egyptians, now accounts for up to five per cent of Egypt's 6.4 per cent domestic inflation rate, estimates Tarek Selim, an economist at the American University in Cairo and an economic advisor to the Egyptian Competition Authority (ECA).

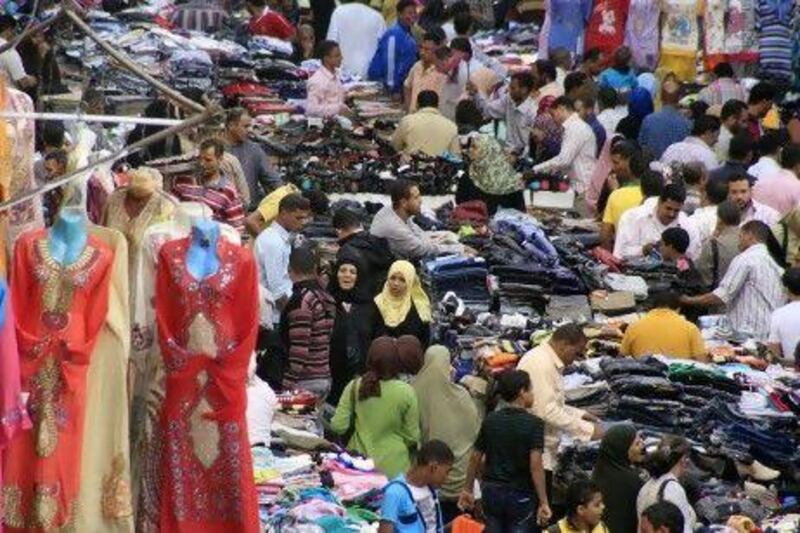

Despite evidence that companies across Egypt have conspired for years to keep prices artificially high, the ECA has been hampered by weak regulation and the existence of a massive informal sector over which the government has no control at all.

"If we don't formalise all businesses in Egypt, we will continue to face the same problems," he said, referring to the importance of connecting businesses with regulation, taxation and other types of government monitoring to stop them from existing off the books.

At the core of the phenomenon of corruption in Egypt is a regulatory scheme, administered by a sprawling bureaucracy, which is weak, Byzantine and selectively enforced.

For that, Mubarak and his predecessor, Anwar Sadat, are to blame, since they did not implement free-market economic policies across the board, said Sameh Torgoman, the former chairman of the ECA and ex-head of the Cairo and Alexandria Stock Exchanges.

"Since Anwar Sadat adopted his open-door policy for the economy, we have been talking about free-market policies but we haven't applied them," he said. "Sometimes you found the government interfering in a way that is anti-competitive."

From regimes that often operated at odds with their own free-market rhetoric emerged economies permeated by conflicts-of-interest, where the government would regulate some sectors but make exceptions for the powerful.

"What we saw over the years was private business and public office aligned," Mr Torgoman said. "This affected decision-making."

The major challenge now facing Mr Morsi's government and the new parliament scheduled to be elected later this year is to offer a vision for the economy that provides businessmen and foreign investors with a clear set of ground rules. Only then, Mr Torgoman said, can appropriate laws be written and regulators brought under control.

Even that, however, is only the beginning of trying to eradicate corruption and fix what has become a "way of life" in the "soft state" of Egypt

"It will require many years to undo the harm that was inflicted on the country over last 30 years, and it will not be easy," Mr El Sawy said.

bhope@thenational.ae

Follow

The National

on

[ @TheNationalROAM ]

& Bradley Hope on

[ @bradleyhope ]

This article has been changed since original publication. We originally said that Mubarak’s successor Anwar Sadat did not implement free-market economic policies across Egypt. Anwar Sadat was Mubarak’s predecessor.