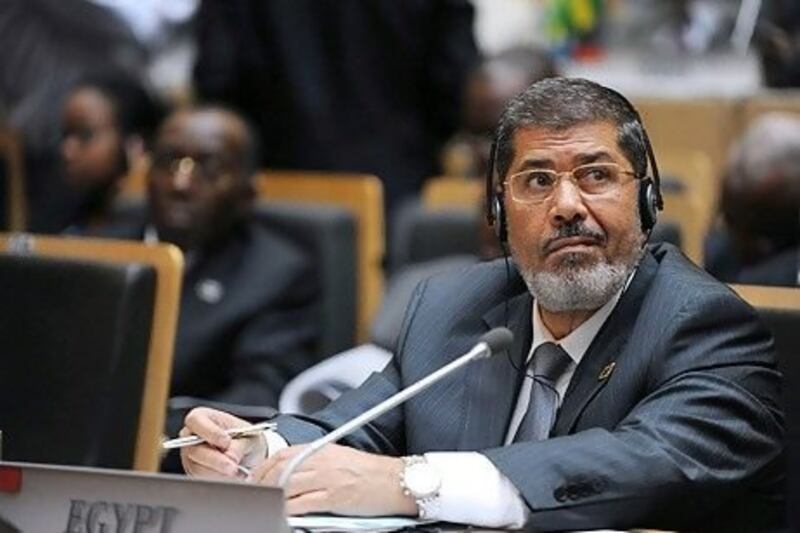

CAIRO // Determined but facing formidable odds, Mohammed Morsi's actions in his first weeks as Egypt's president have been a gamble. From his three inauguration day speeches to his surprise decision to defy a military order dissolving parliament, Mr Morsi has taken huge - some say reckless - risks.

Critics claim he is on a power grab, while trying to help the Muslim Brotherhood realise its dream of an Islamist Egypt. Supporters say he is a revolutionary struggling against old regime institutions determined to keep things unchanged and deny him real power.

To bolster his revolutionary credentials, Mr Morsi's first order as president was to create a committee to investigate the killing of hundreds of protesters during the 18-day uprising that toppled the former president Hosni Mubarak last year. That was a nod to the non-Islamist groups who engineered the uprising in the hope that they would rally behind him in his battle with the military over restoring the powers of his office.

But that strategy has not worked.

The crowds gathering in Cairo's Tahrir Square on an almost daily basis to press for the reinstatement of the Islamist-dominated parliament and the restoration of the powers of the president are drawn almost exclusively from the ranks of the Muslim Brotherhood or allied Islamists.

Many in Egypt have decided to keep their distance from the Brotherhood following attacks, blamed on young members of the group, on politicians and lawyers who filed cases against Mr Morsi's order last week to recall parliament.

Mr Morsi's win in last month's presidential run-off - about a million votes more than those won by Mubarak's last prime minister, Ahmed Shafiq - followed a deeply polarised election in which voters cast ballots in favour of Mr Morsi or Mr Shafiq simply because they did not want the other to win. Many voted for Mr Morsi out of spite against the military, whose generals have been rumoured to favour Mr Shafiq, a career air force officer.

Mr Morsi's order to revoke the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces' decision to dissolve parliament drew a polite but firm response from the military. It stated its commitment to "legitimacy, the law and the constitution". The Supreme Constitutional Court, whose June 14 verdict led to the military's move against the legislature, said its verdict was final and binding.

In response, Mr Morsi's office issued a statement saying the president has nothing but respect for the judiciary and that his order to recall parliament, which convened for five minutes last week, was intended only to create a mechanism for implementing the court's verdict.

The upshot is that Mr Morsi is willing to do battle with the military and the country's highest tribunal, despite the risk of more upheavals.

Even if the legislature were reinstated, it would not sit for more than a few months. A constitutional declaration issued by the military on June 17 says parliamentary elections are to be held within two months of the adoption of the new constitution, now being drafted by a panel selected by the dissolved legislature.

It is also expected that the military, which has veto power over the process of drafting a new constitution, will include a clause providing for new presidential elections.

So why is Mr Morsi risking so much when the object of his efforts - the reinstatement of the Islamist-led legislature - will not last long even if he should succeed?

Perhaps Mr Morsi is trying - too hard and too soon - to assert his authority as well as shrug off his image as an "accidental" president whose loyalty is to the Brotherhood, his home for 40 years. Mr Morsi was in the race because the Brotherhood's first-choice candidate, its chief strategist and financier Khairat El Shater, was disqualified over a Mubarak-era conviction.

The Brotherhood wants the legislature back so its MPs - who control just under half of its 508 seats - can pass legislation to restore some of the credibility lost during the past six months when the group struggled to make quick improvements to the lives of poor Egyptians, or place the economy on a recovery path.