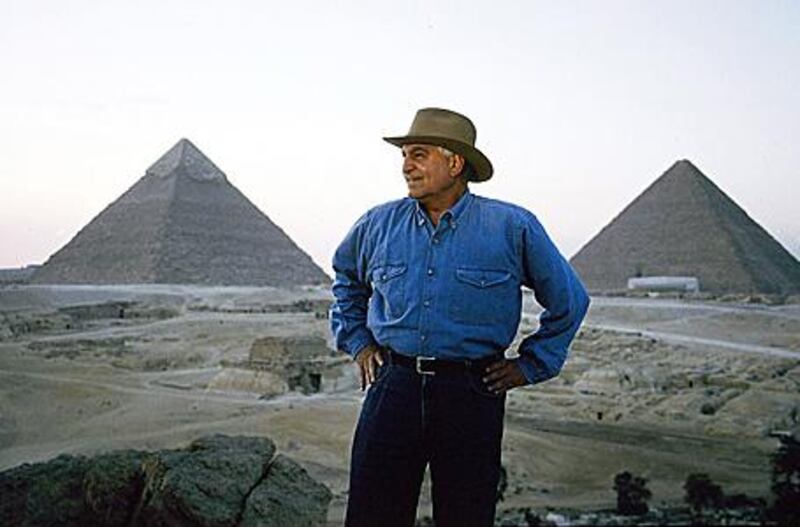

Zahi Hawass has succeeded in persuading museums around the world to return ancient treasures to Egypt, and has ambitions to recapture even more. But is the modern state's claim on pharaonic artefacts truly legitimate? Matt Bradley, foreign correspondent, reports from Cairo. A great deal has been said about Zahi Hawass, the secretary general of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities. He has variously been described as egotistical, charismatic, unscrupulous and, sometimes, well-dressed.

But as far as Mr Hawass's primary goals are concerned, he could also be called successful. This week, in what might be his boldest move yet, Mr Hawass watched as the Louvre Museum, the Parisian temple to the past, returned five ancient frescoes that he said had been illegally plundered in 1980. The Louvre agreed to return the pieces only after Mr Hawass suspended Egypt's archaeological co-operation with the museum in October.

Since he became Egypt's chief archaeologist in 2002, Mr Hawass has undertaken a personal mission to repossess many of ancient Egypt's far-flung artefacts while re-imagining Egyptology - long dominated by Europeans - as a discipline for the Egyptian people. Egypt's archaeologist-in-chief said he had already overseen the return of some 5,000 pieces from museums and collections abroad. Buoyed by his recent successes, Mr Hawass has called for an international conference next March for countries who are seeking the return of ancient objects. Greece, Italy, China and Mexico will be among about 12 nations he expects to attend.

He also plans to enter into negotiations with Berlin's Neues Museum tomorrow for the return of the bust of Nefertiti. Earlier this week, Mr Hawass announced that he would renew calls for the British Museum in London to return the famous Rosetta Stone, which the museum has displayed since 1802. "I will tell them that we need the Rosetta Stone to come back to Egypt for good," Mr Hawass told the Reuters news agency last week. "The British Museum has hundreds of thousands of artefacts in the basement and as exhibits. I am only needing one piece to come back, the Rosetta Stone. It is an icon of our Egyptian identity and its homeland should be Egypt."

Mr Hawass has styled himself as the protector of his country's ancient patrimony and, indeed, the modern Egyptian identity. But his aggressive efforts have raised questions among archaeologists about the nature of antiquities and those who should possess them. For Mr Hawass, the ownership debate transcends the legal distinctions between theft and property rights. Instead, he views the vestiges of ancient history through the contemporary lens of the modern Egyptian state and its history of colonial domination.

"I think this is wrong. We, even if the Rosetta Stone is in England, we own that stone," Mr Hawass told Riz Khan, a reporter for Al Jazeera English, in a 2007 interview. "Egypt has the right. It doesn't mean that if you have an artefact in your museum that you own it. No, the motherland should own this." Mr Hawass's mentality may be younger than the pharaohs, but it is certainly not new. In the 1930s, Taha Hussein, a prominent nationalist philosopher, popularised the idea of Pharaonism, which sought to divorce the Egyptian identity from its Arab and Islamic influences. Indeed, politicians throughout the world have long sought to connect their modern nation states to ancient civilisations.

Ask an Egyptian about his ancient ancestry and he will probably say that he is descended from the pharaohs. But centuries of foreign incursions have left Egypt a melting pot of peoples from Africa and Asia. In almost every respect, the modern Egyptian bears little resemblance to his pharaonic "ancestors". So is it only by accidents of geography that ancient art should belong to a modern state? "Things don't have national cultural identities. People give them those by claiming them," said James Cuno, the director of the Art Institute of Chicago and author of Who Owns Antiquities? "I think we have to be very careful to assume that there is a cultural, even racial or ethnic relationship between a thing that was made and a people that claim it."

It is the habit of political elites throughout the world to manufacture patrimonial claims on ancient art, said Mr Cuno, and such claims rarely amount to a true populist demand. "I'm always very cautious about the rhetorical formulation of 'the people'," he said. "We don't know how 'the people' feel and we know that the government is, as any government is, a government of the elite trying to perpetuate its hold on power."

Yet to say that such sentiments are nationalistic or illogical is to understate the genuine affinity that modern Egyptians feel for an ancient history they are proud to call theirs alone. "They must be returned to us because they are ours," said Mo'men Mohammed, who was strolling through downtown Cairo on Thursday. "They established the civilisation in which we are living now." But even if that argument resonates among most Egyptians, it would almost certainly be ignored in a court of law, said David Gill, a history and classics professor at Swansea University. After all, questions of legality do not answer to ethics alone.

"I would say that there is a very weak legal case to be made, but I think there is a very strong moral case to be made for this shortlist of significant objects to be displayed in Egypt," said Mr Gill of the five main items Mr Hawass has identified as needing to be returned: the Rosetta Stone in the British Museum; the statue of Hemiunu at the Pelizaeus Museum in Hildesheim, Germany; the Dendera Zodiac, which is also at the Louvre; the bust of Queen Nefertiti at Berlin's Neues Museum; and the bust of Prince Ankhhaf at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

"To me the argument is much more about 'here is a unique icon of Egyptology, here is the stone that was used to unlock hieroglyphics'. It is so significant for the study of Egyptology that it's more appropriate for it to be in Egypt," said Mr Gill of Mr Hawass's request for the Rosetta Stone, the metre-high rock that allowed archaeologists to translate ancient Egyptian text into classical Greek. Napoleon's army unearthed the stone in northern Egypt in 1799, but it was ceded to the British after Napoleon's defeat near Alexandria in 1801.

Unfortunately for Mr Hawass, all of the items on his wish list were removed from Egypt before 1970, when delegates to Unesco, the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, drafted the Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. That treaty was the first to set international guidelines for policing the smuggling of antiquities.

Still today, there is no international legal mechanism for adjudicating smuggled cultural property. That task is left to the judicial systems of acquiring countries, which tend to return properties only where there is genuine evidence of theft. Faced with requests such as those of Mr Hawass, some European museums have found a comfortable middle ground. Katja Lembke, the director of the Germany's Pelizaeus Museum, said she and Mr Hawass decided on a partnership to allow for the temporary exchange of artefacts as part of an international travelling exhibition. The partnership will be the first occasion in which Egyptian museums would borrow as well as lend their artefacts. The Pelizaeus Museum's statue of Prince Hemiunu will travel to Egypt after the opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum, a US$592 million (Dh1.99 billion) colossus scheduled for completion on the Giza plateau in 2012 or 2013.

"This is the land of the Nile, so there is a connection between the old period of the pharaohs and the modern times, in my opinion," said Ms Lembke. "But on the other hand, of course, the pyramids are one of the most touristic points, one of the points you have to see before you die for everyone in the world. So it is not only the national heritage of Egypt but world heritage." That may be so, but for most Egyptians, such lofty nuances are immaterial to the more finite question of who should own what.

"Whether it's from the past or not, they are our objects," said Rabab, 19, a Cairo University student. "We made them. Not you." * The National