TIMBUKTU // The shrine of Sidi Mahmoud is cracked and crumbled, with bleached stones that were once ornamental doors and walls sinking into the fine Sahara sand.

A tourist guide who brought visitors to Timbuktu before the town was taken over by Islamist rebels recounts local beliefs about the saint. It is said that the man, who is thought to have lived in the 16th century, was sighted in Mecca, while remaining physically here, that when it rained he did not get wet and that if you prayed at his grave you would be blessed with children.

But 500 years of veneration in Timbuktu came to an abrupt end last summer, when militant Islamists imposed a brutal set of rules on the town and denounced the tombs of Muslim saints as idolatrous. They smashed up this graveyard on the edge of town, where ordinary people's resting places are marked with clay pots alongside the elaborate tombs.

Abdelrahman Al Aqib is the imam of the Sankore mosque. Wrinkled and white-robed, with a shaft of sunlight falling on him as he sits in his darkened diwan, it would be difficult to say whether the man or the mosque has the closer ties to Timbuktu's storied past.

"Sidi Mahmoud was my ancestor," says the imam sternly. "A saint. It was the first tomb they broke." The desecration, he said, caused him physical pain. "There is pain even now. I don't want to talk about that."

The invaders had Timbuktu's antiquities in their sights, including collections of centuries-old manuscripts in libraries and private collections, a huge archive handed down from days when Timbuktu was a centre of Islamic learning. After months of occupation, the militants affiliated to Al Qaeda burnt some of the manuscripts.

But the majority were smuggled to safety by a population with a deep connection with the past and sense of the value of heritage, for whom the writings and the shrines are not fragments of a distant history but part of traditions still alive and vibrant today.

Imams and judges with the Aqib family name have been recorded serving and restoring the Sankore and other Timbuktu mosques since at least the 16th century.

The mosque itself was built 1,000 years ago, later remodelled into a scaled-down, mud replica of the Grand Mosque in Mecca, by one of the Al Aqib family. It formed a central part of a university that was said at its height to have 180 Quranic schools and 25,000 students. Sidi Mahmoud, the saint, was the great uncle of one of the school's foremost scholars, Ahmed Baba - a historian on the cusp of the 17th century - to whom today's imam also traces his lineage.

Mr Al Aqib said that when the militant Islamist groups first took over Timbuktu as they seized the whole of northern Mali in April last year, their leaders came to him and asked to pray in the Sankore mosque.

"I told them they couldn't pray in the mosque," he said. "I want nothing to do with them." They left him alone - although he says they disrespected his colleagues. But they then turned their attention to the Ahmed Baba Institute, just across the square.

The Institute's handsome new building, mud-coloured but built with modern materials, has climate-controlled storage, reading rooms, a conference area, elegant lamps. But though the South African-funded centre was opened in 2009, its employees say that only 2,000 manuscripts had actually been transferred from an older library into the centre.

Before the militants worked out to look in an older building for the remaining 28,000 manuscripts, said Abdoulaye Cisse, the acting director of the institute, he and the other archivists and employees quietly began to smuggle them out of the city. They piled centuries-old investigations of law and geography, the volumes known in Arabic as the Histories of the Sudan, and Islamic scholarship, into rice sacks.

Taking care to travel at prayer time and take back roads, so as to avoid the zealots, four or five employees working for two weeks gradually moved the papers to the home of the director of the institute, Abdul Kader Haidara. From there, he sent them down the river Niger in metal suitcases on canoes, or moved them by road to the capital, Bamako, and safety.

"The jihadists came to the house of Haidara, and said 'you have been helped by Americans to build your library, so we will take the manuscripts,'" said Mr Cisse. "But it was one week after they had gone."

"We are very proud of what we did," said Khalif Al Hadji, an archivist. "We did it for three reasons. The first, is that if we lose these manuscripts, we won't find them again. Two, we work in the library. Three, we are all Malians and we know exactly how valuable these manuscripts are to us."

Mr Cisse added proudly that the rich archive of thousands of books belie the myth that Africa relies on oral tradition as opposed to written history and scholarship. "It's enormous," he said. "The culture, the history."

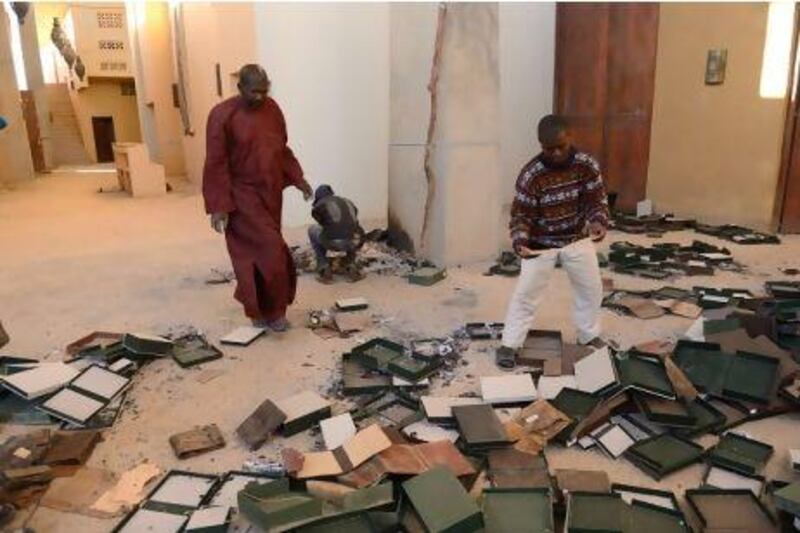

Even as the men spoke, in a courtyard of the new building, ashy fragments of burnt manuscripts eddied in the breeze. Just before a French-led intervention had pushed the militants out of town, some of the rebels pulled around 1,000 manuscripts off the shelves and built a bonfire. The charred scripts are still discernible, but the treasures are lost.

French soldiers have now left Timbuktu, and there are fears that the militant Islamists could creep back, and a similar fate could await any of the manuscripts returned to the institute. Under the circumstances, the manuscripts are unlikely to go home for some time, said Shamil Jeppie, head of the Tombouctou Manuscripts Project at the University of Cape Town.

For now, he added, "our concern is more neglect." Without archivists and conservators to keep the paper at a stable temperature, the fragile books are at risk. They will also need re-cataloguing.

Yet he remains optimistic. "It's bad. But it's not all that bad," he said. The city has been invaded many times before, and there are through the centuries tales of copyists making new versions of the manuscripts, or burying them in sand to hide them from colonial-era French thieves. The pragmatic approach to storing books, he said, belies the idea that one needs an imposing building to form an archive - this rich culture is built more on a "mobile archive" that improvises and has existed for centuries.

"They copied things, they conserved the content of the manuscripts. There's lots of subtlety there," he said. "People are almost genetically trained to preserve things."

afordham@thenational.ae