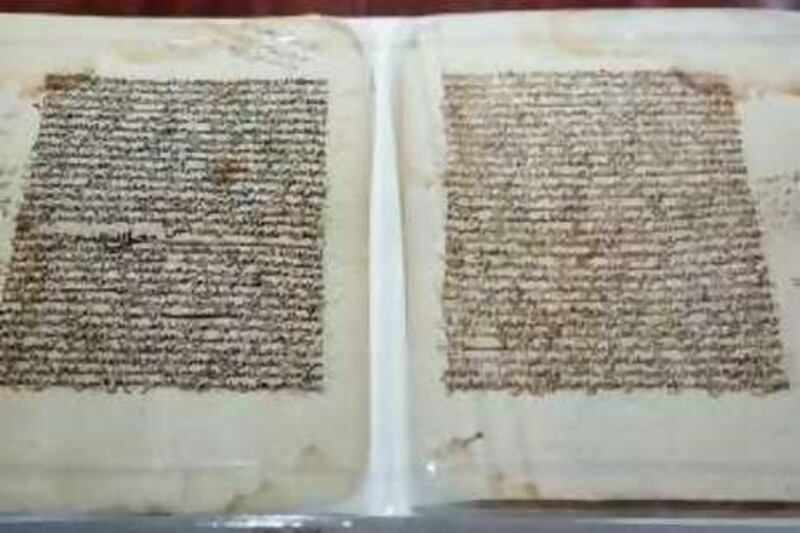

JOHANNESBURG // The words tumble precisely across the pages, exact Arabic script lining up in neat rows across ancient sheets of paper from a city of legend. A total of 40 manuscripts from Timbuktu, once a great seat of learning and wealth but now a remote outpost in the Malian Sahara, have gone on display in Johannesburg. It is the final stop in a touring exhibition, the first time many of them have left the city in centuries, that represents an attempt to begin an African cultural renaissance - and at the same time an indication of how the mighty have fallen. Founded in 1180, long after the spread of Islam into the area, Timbuktu - the name means "the well of Buktu", was initially a Touareg oasis and settlement, but in the first half of the past millennium it developed into a great trading hub. From the north, caravans would cross the desert bringing salt, pepper, manuscripts, ostrich feathers and other goods. From the south, traders brought slaves, gold, ivory and cereals. They met in the mud settlement on the banks of the Niger, almost at the centre of west Africa, and a great city and centre of learning grew up. Its reputation truly began to spread when Mansa Musa, the ruler of Mali, went on Haj to Saudi Arabia in the 1320s. Accompanied by 1,000 people, the expedition took so much gold that when it arrived in Egypt the price of the metal crashed. In the 16th century, the Andalusian-born historian and traveller Leo Africanus wrote: "The rich king of Timbuktu has many plates and sceptres of gold? he keeps a magnificent and well-furnished court, there are numerous doctors, judges, scholars, priests and here are brought manuscript books from Barbary which are sold at greater profit than any other merchandise." Successive rulers promoted scholarship as well as power - even now private households in Timbuktu possess extraordinary collections of works - and the manuscripts on show in South Africa are evidence of how advanced the culture became. One, The Rights of the Prophet, contains a genealogy of Mohammed going back 21 generations. Another, The Joyous Companion of Those Whom I Met of the Maghribi Men of Letters, dating from 1721, contains biographies of 100 literary figures, and one of the oldest is the Tarikh al Sudan, a history of the "black country", as opposed to the modern-day nation of that name, originally written at the turn of the 17th century. Theological debate is also to be found - in one document, the great scholar Ahmed Baba, for whom the institution archiving the manuscripts is named, discusses the importance of studying Islam. "On the day of judgement the ink of the scholars will be measured against the blood of the martyrs and found to be weightier," he writes. But by the time Europeans finally reached the fabled citadel in the early 19th century, it was already a pale shadow of its former self. As Europeans began exploring and trading along the African coast, the routes of commerce had changed and the caravans no longer came to Timbuktu. Occupied by Moroccan forces in 1591, centuries of political instability and insecurity had followed, and growing desertification had done nothing to help. "History comes in rotation," said Mohamed Diagayete, 38, a researcher at the Institut des Hautes Études et de Recherches Islamiques Ahmed Baba, which is the centre conserving the manuscripts on display. "Each plays a role at one time, once you reach the summit it's obligatory to go down, you can't stay there." Now the balance of power has changed again in Africa, and it is South Africa that is the economic driver of the continent. The exhibition is the result of the first cultural programme of the New Economic Partnership for Africa, with South African funding and technical expertise helping to preserve and research the manuscripts and display them to a wider audience. "These texts are not only for Muslims, it's for Africans and for the world in general," Mr Diagayete said. "We have the raw materials, and the south has the modern capacity." There is a certain irony in that, with very few exceptions, almost no sub-Saharan African cultures developed written languages of their own, and it was the arrival of Islam that brought with it a script, in the form of Arabic. Thabo Mbeki, who when he was the South African president was a driving force behind the project, said when the exhibition opened in Cape Town: "These materials point to a lively and changing intellectual environment in and around Timbuktu; they express an African intellectual engagement with a larger world of ideas going beyond the borders of the continent yet firmly rooted in a local setting. "There is an urgent need to rethink African history, there is an urgent need to do more research and produce a new body of knowledge about Africa and there is an urgent need for Africa to define herself." For some it is a sensitive topic. On its website, the California-based Timbuktu Educational Foundation, said: "The translation and publication of the manuscripts of Timbuktu will restore self-respect, pride, honour and dignity to the people of Africa and those descended from Africa. "It will also obliterate the stereotypical images of Tarzan and primitive savages as true representation of Africa and its civilisation." sberger@thenational.ae

Exhibition hints at past glory

A total of 40 manuscripts from Timbuktu, once a great seat of learning and wealth, have gone on display in Johannesburg.

Editor's picks

More from the national