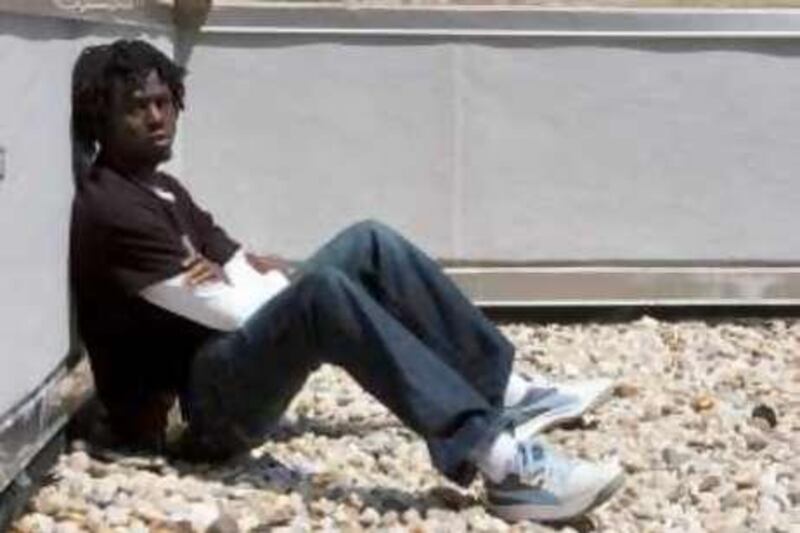

UNITED NATIONS // Emmanuel Jal is not certain, but thinks he was six years old when he was forced to fight alongside southern rebels in Sudan's bloody civil war, becoming a hate-filled gun-toter, determined to "kill as many Arabs or Muslims as possible".

Today, Mr Jal is an emerging star of Africa's rap scene, with lyrics on his recently released second album, WARchild, fuelling debate on one of the most complex moral issues of the modern era: child soldiers. The talented performer demonstrates how underage combatants can be rehabilitated, but his memories of ruthlessness and horror before he became a teenager remain extremely provocative. "When I first held the AK-47, I became very powerful," said Mr Jal, describing events in 1987, four years after the start of a conflict that left 1.9 million dead. "What I remembered was my village. My aunt who was raped. My house that was burnt down.

"I forgot that I was a child and I wanted to kill as many Arabs or Muslims as possible. And that's a desire. When you are given that gun, you want to get revenge." Mr Jal's powerful lyrics echoed through UN headquarters in New York as part of a conference series in which delegates grappled thorny topics, including how professional armies and peacekeepers should respond when they encounter child soldiers on the battlefield.

Radhika Coomaraswamy, a UN special representative whose portfolio is children and armed conflict, describes a massive increase in the use of child soldiers over the past six decades, with 250,000 fighting in 57 forces around the world - mostly in Africa, Latin America and the Middle East. "There has been an incredible rise in the number of child soldiers since the Second World War, culminating in the 1980s and 1990s where it reached its peak of about 300,000," Ms Coomaraswamy said. "It is argued by many that it is really the proliferation of small arms that has actually contributed to this rise."

Guns have become cheaper, lighter and more accessible, with serviceable weapons available for just US$5 (Dh18) in most developing countries. The business now involves 600 firms in 95 states and, in 2000, saw illegal traders double the turnover of legitimate dealers with sales estimated at $10 billion. Children in war-torn countries are "manipulated and exploited by cynical, brutal adults" to become efficient and cold-blooded killers, Ms Coomaraswamy said. "It takes a child 40 minutes, on average, to master an AK-47."

"Some children are abducted into armed conflict, but others join voluntarily because of ideological reasons, poverty, grievance or revenge. There are many reasons," Ms Coomaraswamy said. "They talk about the power that it gives them when they carry weapons and control the population. The gun gives the child complete power over others, even elders, and destroys the social fabric in that society, as children become the leaders, and elders have to cow to that weapon."

A new feature film titled Johnny Mad Dog, which won the Prize of Hope at this year's Cannes film festival and is screening at other festivals around the world, offers insight into the unspeakable horrors children unleash when toting guns in a war zone. The film graphically depicts a drug-crazed unit of boy soldiers marauding through the chaos of an unnamed African civil war raping women, butchering civilians and chanting their bleak anthem: "If you don't wanna die, don't be born."

Stephen Rapp, prosecutor of the Special Court for Sierra Leone, established to try those responsible for war crimes during the West African country's nine-year civil conflict in the 1990s, is acquainted with the capabilities of killer kids. "They are torn from their communities, put on dope and given a persona like Rambo," Mr Rapp said. "They can commit acts of brutality that many adults would not commit. In Sierra Leone, one of those involved in the amputations, Dr Chop Chop, who became proficient at chopping off arms and limbs of adults and children, was himself 12 years old."

Jean-Maurice Ripert, France's ambassador to the UN, has been active in framing international standards that define child soldiers "primarily as victims, exposed to unbearable violence and deprived of their childhood". During a security council debate, Ban Ki-moon, the UN secretary general, cited a "solid body of international standards" relating to children and war, notably the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which criminalises the recruitment of children younger than 15 into fighting units.

Nevertheless, Mr Ban lamented the fact that "we have only begun to scratch the surface" of the problem. Only a handful of child soldier recruiters have been brought to justice. Ms Coomaraswamy echoed the concerns, calling for the council to begin "targeted and concrete measures" against repeat violators of children's rights. Although Mr Rapp lauds the world's first successful prosecution of individuals responsible for recruiting child soldiers - three rebel leaders from Sierra Leone's civil war, convicted last year of a range of war crimes charges - he talked about the difficulty of making allegations stick.

His colleagues running the ICC in The Hague have bigger problems, such as Joseph Kony, head of Uganda's Lord's Resistance Army and alleged to be responsible for abducting an estimated 60,000 children and forcing them into ragtag combat units or sexual slavery. Kony remains at large despite an arrest warrant that was issued in 2005. Tensions were raised further when UN analysts discussed how peacekeepers should respond when engaging a hostile but underage enemy in the field: a complex moral argument that must balance the rights of child soldiers against those of professional forces.

Ms Coomaraswamy contended that children, "regardless of whether they wear a uniform or not, are civilians, and the only time you can use force against them is in self-defence". But blue-helmet troops take a different stance on engaging children. Peacekeepers try "everything possible to avoid a confrontation" with child soldiers, but rules on the battlefield are very different, an official said. "The age of the attacker is not a part of calculation once we've entered into the realm of protecting our forces," the official said. "In some situations, this will be when we are being fired at. In other situations, it can be when there is a perceived threat."

After several alterations, the council debate concluded with an agreed presidential statement in "condemnation of the continuing recruitment and use of children in armed conflict". But for Mr Rapp, attitudes in the outside world are taking too long to change. His prosecutions of child soldier recruiters in Sierra Leone, he said, surprised a population that was previously not alarmed by the idea of arming 12-year-olds.

His concerns are borne out by global evidence, with images of teenage suicide bombers still hanging as martyrdom tributes in Palestinian camps, and a worrying trend among Yemeni families to order boys to commit honour killings - thus escaping the death penalty should they get caught. Even the country that convened the debate, Vietnam - which presides over the security council this month - was unwilling to wholly tackle the moral ambiguities surrounding the use of children in conflict.

When asked whether it had been acceptable for the Viet Cong to use children against vastly superior US forces during the 1970s war, Pham Gia Khiem, Vietnam's deputy prime minister and minister of foreign affairs, ignored a body of historical evidence. "Vietnam has never involved children as combat troops," he answered. @Email:jreinl@thenational.ae