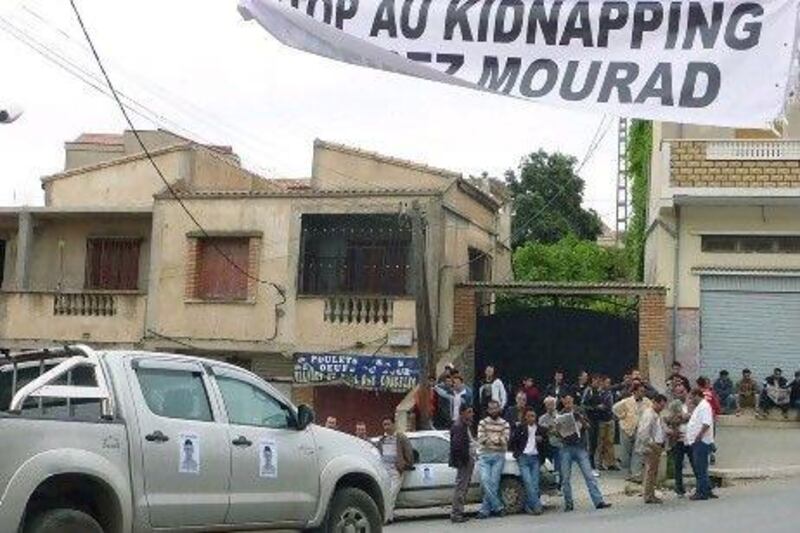

ALGIERS // Weary from years of kidnappings, the inhabitants of Algeria's Kabylie mountains are finally turning against the Al Qaeda fighters in their midst and are helping security forces to hunt them down.

And that turnaround is giving Algeria its best chance to drive the terror network from its last stronghold in the country.

While defeated in much of Algeria, Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (Aqim) remains active in the Kabylie.

This is partly because the Berbers there, the region's original inhabitants before the arrival of the Arabs, have long been hostile to the central government and have refused to provide information on militants whereabouts or activities.

The situation began changing after a string of militant attacks over the summer culminated in a brazen daylight assault against a police station. That attack prompted Algeria to hold an emergency security meeting to devise a new strategy against the militants, said a high-ranking official privy to the meeting.

A pillar of the resulting counterterror plan was to exploit frustrations over kidnappings to win the Berbers over to the government side, said the official.

The strategy appears to have worked in spectacular fashion.

It first bore fruit with the capture early last month of a military commander. But the biggest coup came on October 14 with the killing of Aqim's head of external relations, Bekkai Boualem, also known as Khaled El Mig.

In the following two weeks, four other suspected militants were ambushed and killed by security forces following tipoffs from the local population.

The successes have some Algerians hoping that the country may finally quash a decades-old Islamist insurgency.

But Riccardo Fabiani, the North Africa analyst for the London-based Eurasia Group, cautioned against pronouncing the end of Al Qaeda in the Kabylie region too quickly, since the government keeps a tight lid on all information regarding the battle against the militants.

"There are no reliable statistics on terrorists in Algeria," Mr Fabiani said. "No one knows anything about how many new recruits there are every year, how many people abandon terrorism within the framework of the national reconciliation programme, how many people are actually killed."

Mr Fabiani also noted that, to some extent, it serves the government's interests to have a constant low-level threat in an area remote from the capital to remind people about the darker days of the civil war.

And violence isn't eradicated yet. On October 18, a group of armed men stopped a bus at a fake checkpoint in the Boumerdes region and checked passengers' identity papers until they found two members of the military.

They dragged them from the bus and shot the military men dead before disappearing into the bush.

* Associated Press