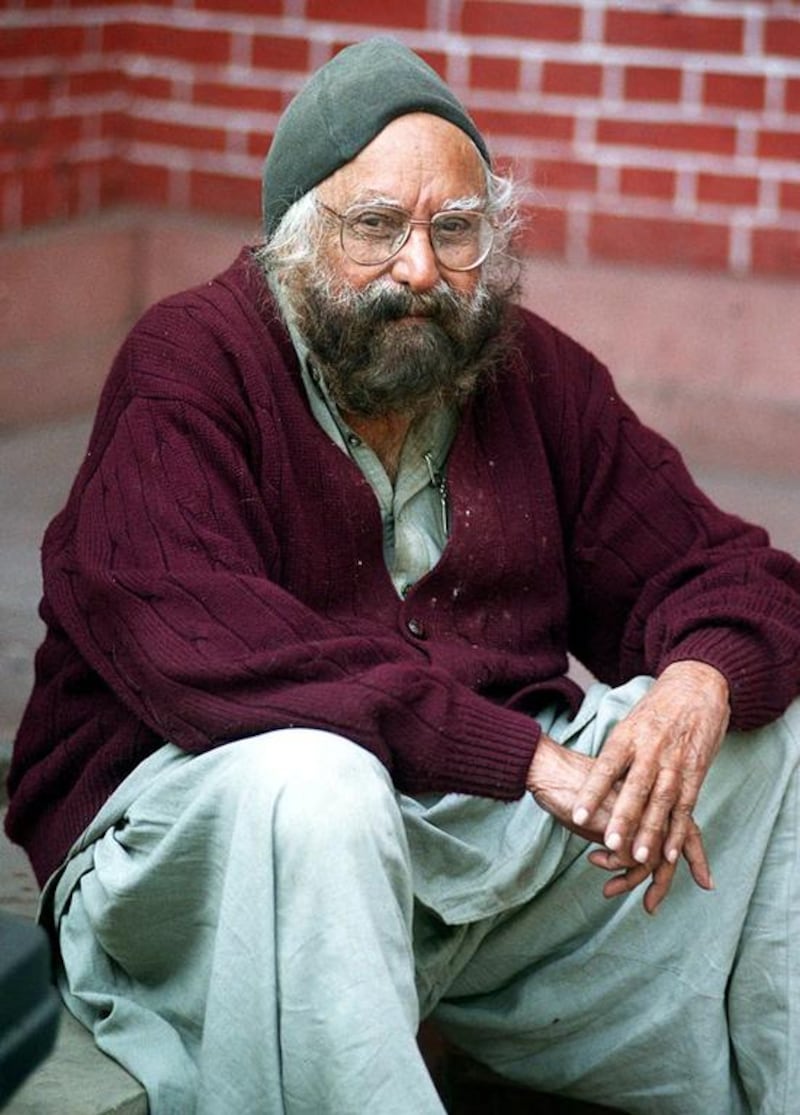

NEW DELHI // Khushwant Singh, one of India’s most prolific and beloved writers, died yesterday at his New Delhi residence at the age of 99.

Singh was best known for his wicked sense of humour, which manifested itself in weekly magazine columns that he wrote well into his 90s, and in books such as The Good, The Bad and the Ridiculous, published last October.

Singh’s most common literary persona was that of a hard-drinking, decadent Sikh, a “dirty old man” who pursued every worldly pleasure that life had to offer.

But in his other books – he wrote or compiled more than 80 books – Singh displayed keen scholarship, a sharp eye for both fiction and journalism, and a powerful grasp of the history of India’s Sikh community.

Singh's multi-volume A History of the Sikhs is lauded as the definitive account of the evolution of the Sikh religion. His Train to Pakistan, an acclaimed novel set during the bloody partition of India in 1947, was made into a film in 1998. During his editorship of the Illustrated Weekly of India, from 1969 to 1978, he raised the magazine's circulation from 65,000 to 400,000.

Born on February 2, 1915 in a district of Punjab that is now in Pakistan, Singh came with his family to Delhi soon after. His father Sobha Singh, a builder and real-estate baron, received the commission to construct much of central New Delhi, being rewarded for his efforts with a knighthood.

Having tried and failed to enter the imperial civil service, Singh focused on his studies and eventually received a law degree from King’s College London in 1938 and then qualified for the London Bar. Once India became independent in 1947, he became a diplomat. It was during his postings in Canada, France and Great Britain that he began to write.

After the publication of Train to Pakistan in 1956, and the subsequent acclaim, Mr Singh devoted himself to writing.

During his stewardship of the Illustrated Weekly, Singh turned out essay after essay on politics and culture, all of them entertaining and well-written, and many of them sophisticated in style and technique. But he also fell victim to a spell of political misjudgement, supporting the prime minister Indira Gandhi’s imposition of emergency rule in 1975 and showering praise upon Ms Gandhi’s tyrannical son Sanjay.

In a cover story for the magazine in August 1976, The Man Who Gets Things Done, Singh refrained from criticising Sanjay’s misdeeds, such as a compulsory sterilisation programme for men, intended to check India’s booming population.

“Didn’t our slums need clearing? Didn’t our population need to be controlled?” Singh wrote. “Why cavil about someone who is at long last getting all this done?”

In a sort of political redemption, however, Singh took stances of great integrity in the early 1980s. When a militant/ secessionist movement was calling for Punjab to split away from India, Mr Singh opposed it even though, as a Punjabi Sikh, he risked being called a traitor to the cause.

In 1984, Indira Gandhi ordered a military operation on the Golden Temple in the town of Amritsar to root out the leaders of the secessionist movement. The attack on the temple – the Sikhs’ holiest shrine – and the death of 492 people angered Singh. He strongly criticised the operation and returned his Padma Bhushan, the country’s third-highest civilian award.

Singh wrote tirelessly through the 1990s and the 2000s. He rose before dawn, wrote his articles in longhand, replied to letters, and walked around the garden of his house. He entertained guests with great discretion. Outside his door was a notice that read: “Do not ring the bell unless you are expected.”

When an expected guest did drop by, he or she would be offered a courteous drink or two of Scotch. Equally courteously, the guest would be ejected at 9pm sharp, so that Singh could go to bed.

“The world will always remember him as a lovable human being,” author and veteran BBC journalist Mark Tully said told NDTV.

Fellow authors including Vikram Seth and former cricketers were among those who visited his home yesterday to pay their respects.

Singh is survived by his son Rahul and daughter Mala. His wife Kawal died in 2002.

“I had to cope with death when I lost my wife,” Singh wrote in Absolute Khushwant, a collection of his writing that was published in 2010. “At times I broke down, but soon recovered my composure.”

“When the time comes to go, one should go like a man without any regret or grievance against anyone,” he said in the same piece. “[The poet Muhammad] Iqbal said it beautifully in a couplet in Persian: ‘You ask me about the signs of a man of faith? When death comes to him, he has a smile on his lips.’”

ssubramanian@thenational.ae