From the ancient tale of Layla to the modern verse of Nizar Qabbani, poetry of undying love has always held a special place in the hearts of Arab people, and they created a unique genre of romantic verse of express and celebrate it.

Sometime in the late 7th century, a young Bedouin wanders the wilderness of the Arabian Desert. Ranting poetic lines of anguish, he obsessively writes a name in the sands using his finger or a stick – Layla.

“I draw a picture of her in the dust /and cry, my heart in torment / I complain to her about her: for she left me / lovesick, badly stricken / I complain of all the passion I have / suffered, with a plaint toward the dust / Love makes me want to turn to Layla’s land / complaining of my passion and flames in me ...”

Qays ibn Al Mulawwah's legendary poems of undying love for his Layla earned him the nickname Majnoun Layla – crazy for Layla or Layla's madman – and the lover's tragic, unrequited love story is known as the Arabian Romeo and Juliet.

In love with Layla bint Sa’d since childhood, whose “hair was dark as layl [night]”, Qays watched as she was forced to marry another, which drove him mad and into the desert.

“I have been through what Majnun went through, but he declaimed his love and I treasured mine, until it melted me down,” Layla said.

She suffered mostly in silence, while Qays declared to everyone and everything his love for her.

From tribal feuds to secret love letters, their love story ends with them both dying in 688, where it is said they found Qays laying next to Layla’s grave, their broken hearts finally united in death.

The story has inspired various versions of tragic love in different languages and cultures, appearing in Sufism, Persian and Indian poems. This genre of romantic poetry is known in Arabic as Al Ghazal or Al Ghazel.

The western world may know of some of the romantic poems from this region, such as those by the popular 13th-century Persian poet and Muslim scholar Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi and the Lebanese American Khalil Gibran (1883-1931), but there are many others whose love poems are more beautiful than any rose given on Valentine’s Day.

“The Arabs are famous for their seductive, passionate love poems and prose,” says professor Hasan Al Naboodah, an Emirati historian and dean of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at the UAE University in Al Ain.

“There are so many romantic figures in our heritage, and some of the most famous ones are usually stories of unrequited love, where the heroes never married their love in the end,” he says.

Poems of lost love in the desert are also known as Al Ghazal Al Udhri or Udhrite Ghazal, after the tribe of Banu Udhrah who were known for their chaste and self-effacing love for the unattainable woman.

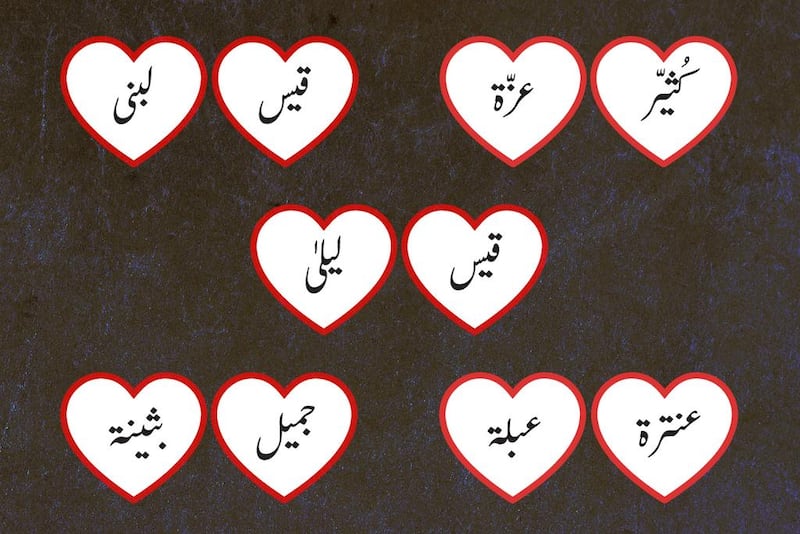

This special genre emerged in the Umayyad period (7th to 8th centuries CE) and includes the timeless real-life love stories of Majnoun Layla, Qays and his Lubna, Jamil and his Buthayna and Kuthaiyr, the lover of Azza and many more.

“It was a kind of an honourable love, where it was not about the physical, but about the soul. Both the male and female poets spoke from their hearts,” the historian says.

“In the pre-Islamic love poems of Antarah Ibn Shaddad (525AD to 608AD), known as the Black Knight, you feel the anguish of this brave former slave who loves his cousin Abla, but is not allowed to be with her,” he says. “He was a warrior, tough, but gentle and broken over his love.”

A rock is named after Antarah in Uyun Al Jiwa, in the north-west Al Qassim province of Saudi Arabia, called Sakhrat Antarah – a site believed to be where Antarah would meet his love Abla, away from prying eyes. Not surprisingly, the rock is now regularly visited by lovers and fans of the knight’s poetry.

But not all are tragic love stories. There are the flirtations of the mischievous 7th-century Umar ibn Abi Rabih who, posing as a hopeless lover, would wait for female pilgrims coming to Mecca, and then pursue them with his poetry.

The Emirati Rashid Al Khadr (1910 to 1980) for example, compared a beautiful woman to “cold fresh water” given to a thirsty man struggling in the heat of the desert.

“Al Ghazal will never die, just today’s Ghazal poetry is not as genuine or deep as those composed and dreamt up by our greatest poets,” the professor says.

In every Islamic period and up to modern times, from simple figures to royals and princes, there have been many poets who ventured into this love genre, their words turned to songs and mottos. Some poets revolutionised this style, such as Nizar Qabbani, who was among the Arab world’s most influential contemporary and sensual poets whose poems can be understood by anyone in love or in search of love.

“I am perhaps the only Arab man who hasn’t used my father’s romantic poems to woo my wife,” says Omar Qabbani, 45, who is the last surviving son of the poet.

The legendary prince of poets was born in Damascus on March 21, 1923 (a city he often referred to as his mother) and died from illness in London at the age of 75 in 1998 after a lifetime of travel as a diplomat, an artist, a poet and a writer.

Qabbani was honoured last year on his birthday, March 21 – also Mother’s Day in the Arab world – as a Google Doodle. The Syrian is known as the “woman’s poet” and “poet of love” for his timeless romantic, sensual, patriotic and feminist lines, as well as being revered for addressing important issues including religion, history and Arab nationalism.

“He had to portray himself as the Don Juan of the Arab world, but he wasn’t like that at all. He was a real gentleman,” says his son, who has been living in Dubai with his family for more than 20 years and runs a marketing company.

In Arabic, Shaer (poet) translated to the feeler – or the one who feels.

“And that is what my father was, a real Shaer,” he says.

“He was a humanist, understanding and sensitive to our plight, he felt the anguish of man, of woman, so that is why his work still touches people from across the world.”

Some of the tributes include a street in his name in Damascus and a bronze bust in Cleveland, Ohio, at the Syrian Cultural Garden.

Hitting a chord even today with their universal, timeless themes of love, heartache, nationalism and dreams, Qabbani’s poems are constantly re-shared on social media, with dozens of accounts set up in his name.

“The light is more important than the lantern,” Omar says, reciting one of his favourite lines from father’s work.

“I regularly meet someone who tells me how my father’s poetry inspired them, touched them, helped them see love differently and even a few who say they used his best lines to seduce their future wives,” his son says.

One of the turning points in the poet’s life came when he was 15, and his 25-year-old sister committed suicide because she refused to wed a man she didn’t love.

From this incident some of Qabbani's most famous quotes were born – Love in the Arab world is like a prisoner, and I want to set it free. I want to free the Arab soul, sense and body with my poetry. The relationships between men and women in our society are not healthy.

Together with a masterly talent for the Arabic language and a philosophical mind, Nizar Qabbani’s words sought to change the world, from inspiring love of self and others, and a deep appreciation for the simplest of things, such as the scent of a flower.

“My father would wake up middle of the night, write down a few poetic lines on, say, the tissue box, and then go back to sleep,” recalls Omar, who has two sons – Nizar, 15, and Faisal, 11, with this young Nizar already showing poetic promise.

“He carries a legendary name, which, interestingly enough, means someone who is sensitive, precious and rare. That is what my father truly was.”

rghazal@thenational.ae