Sulaiman bin Shah was at a wedding earlier this month when he got a tap on the shoulder.

It was the sixth time someone sent by the Taliban, the militant group that now rules Afghanistan, had asked the former deputy minister of commerce and industry to return to his old job.

“They’ve sent people to my home, my private office. They’ve sent family members and friends, but I’ve respectfully declined every time,” he told The National in Kabul on the eve of the anniversary of the Taliban takeover.

Mr bin Shah was only 30 when he was appointed deputy minister by then-president Ashraf Ghani, with whom he frequently clashed.

When the Taliban took control of Afghanistan last August, he was sidelined. Within a few weeks, he stopped showing up to work. Now, the Taliban want him back.

Afghanistan’s economy has shrunk by 20 per cent to 30 per cent since US troops withdrew. The Taliban have taken the country back to 2007 in an economic time machine, at a cost of about a million jobs, and leaving 70 per cent of the population unable to afford food and other necessities, the World Bank reported.

Afghans in Kabul mostly lay the blame for their dire economic prospects on international sanctions taken against the extremist group.

These take various forms, from the nearly $9 billion of Afghan Central Bank reserves confiscated by the US and European countries, to a ban on banks dealing in dollars to avoid the possibility of carrying out any transactions that might allow money to end up in Taliban hands.

The former prevents Afghanistan’s government departments from importing most food or medicine. The latter deters most foreign governments, charities and businesses from dealing with Afghanistan at all.

Although the US Treasury Department, which regulates the dollar-related sanctions, has said exceptions are allowed for humanitarian transactions, the details of these exceptions remain so vague that few want to take a chance.

“Afghan institutions are not technically under sanctions at all … Individual Taliban leaders are,” said Mr bin Shah.

“Unfortunately, the Taliban government has decided to put those individuals in charge of various institutions, which prevents foreign groups from dealing with them. This is something we need to blame the Taliban for.”

Decisions made by the Taliban during its stewardship of Afghan institutions have done little to ease the world’s discomfort.

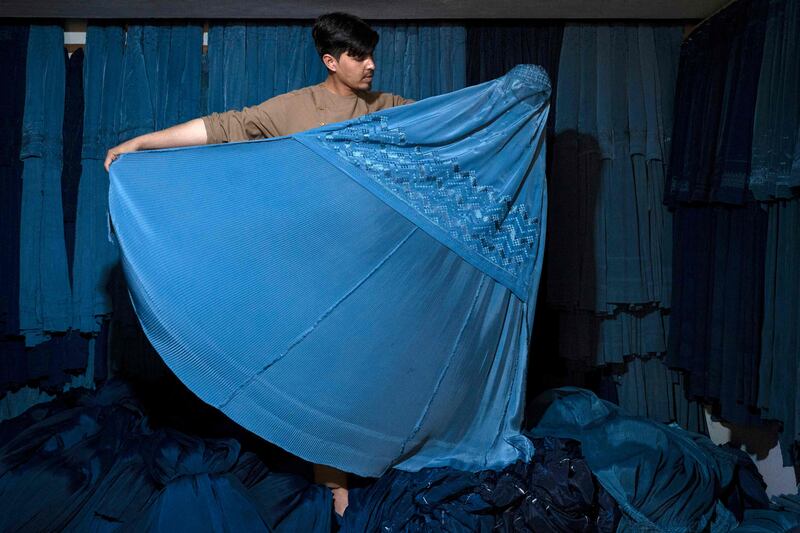

In March, the government’s Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice patrolled government offices and sent home any male employees who declined to grow a beard or wear traditional Afghan clothing. Last month, female employees at the Ministry of Finance were asked to quit their jobs and send a male relative to work in their place.

These actions have left the country without thousands of skilled workers, such as Mr bin Shah, to run departments. And it has led them to chase down those they forced out in the heady days following their return.

Logistics nightmare hinders Afghan entrepreneurs

The sanctions have left businesses seeking convoluted means of receiving payment from overseas buyers, including turning to Bitcoin. Meanwhile, the logistics sector has been decimated, with airlines refusing to ship goods and international firms such as DHL leaving entirely.

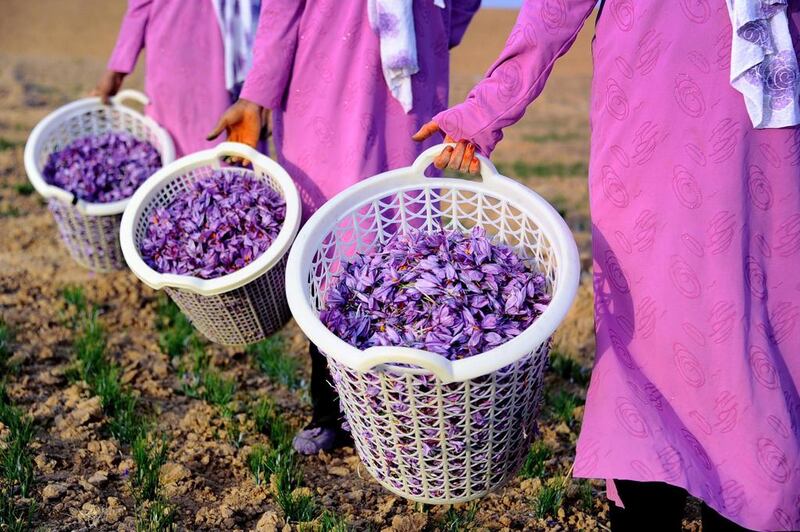

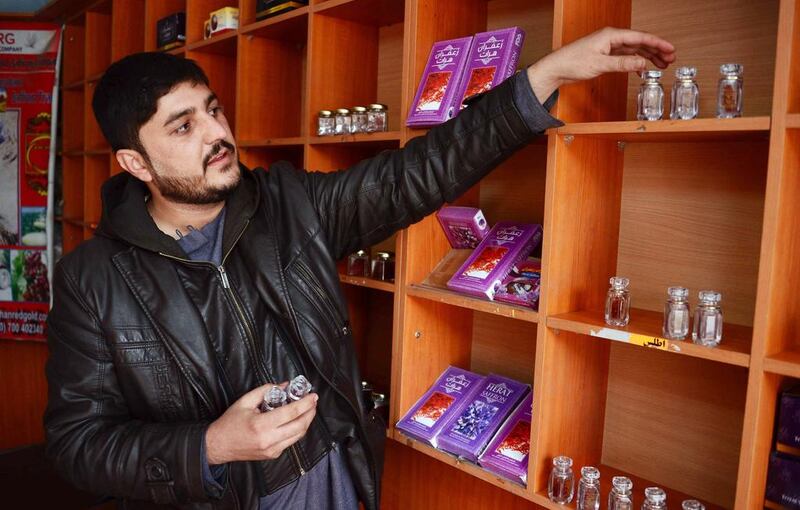

Noor Ahmad and Himayatulhaq Tahiri, both 24, from Kabul, met while studying together at a university in Peshawar, Pakistan, and invested their savings of $1,000 to start a saffron-exporting business in 2021, when the ministry Mr bin Shah worked at was slashing red tape for start-ups.

Sanctions on the Taliban have hit their business hard.

How they ship saffron to their 300 overseas customers changes week by week, depending which lorries are heading over the Afghan border. The crimson spice can travel to Peshawar, Dushanbe or even Tehran before being re-exported in unmarked jars to their intended customers, many of whom are in the West.

The second hurdle is getting paid: without bank transfers available, they’ve turned to Bitcoin.

But the cryptocurrency is extremely volatile, so received payments have to be cashed out quickly to prevent any major losses.

A common method is to use an online exchange to swap the Bitcoin for Tether, a so-called “stablecoin” pegged to the US dollar.

The Tether is then used to purchase UC, the in-game currency for the computer game Players Unknown Battlegrounds (PUBG), which is wildly popular among Afghan youths.

A handful of alternative exchange houses in Kabul deal in UC and buy the in-game tokens for hard cash.

In this new financial world of sanctions and convoluted exchanges, Mr Ahmad and Mr Tahiri have, like many other young Afghans, have become big believers in Bitcoin.

“It’s our future,” Mr Ahmad said.

But Mr bin Shah said there is only so much Bitcoin can do for Afghanistan. Rumours run rampant that the Taliban is exploring a ban on cryptocurrencies — it has already banned PUBG — after a few viral reports in recent months of Afghans losing their life’s savings when the price of Bitcoin plummeted.

“Cryptocurrencies do not have the scale and sustainability needed for Afghanistan’s economy, which really just needs certain foundational things — knowledge, expertise and resources,” Mr bin Shah said.

The flow of corruption briefly stemmed

While sanctions remain a big barrier to investment, so, too, does the spectre of corruption.

“Corruption has been the big monster that has always held up our progress,” said Mr bin Shah. “It became normal for everyone in government to take a cut and it ruined a lot of good deals — prospective investors would often be pressed for bribes, and then just pack up and leave.”

One of the silver linings of the Taliban’s strict rule, many Afghans say, was that corruption briefly diminished. Now, though, they say it is starting to return.

An Afghan businessman, who did not want to be identified, said that under the republic, bureaucrats would charge about 80 per cent in “fees” on the deal. Under the Taliban, that has been reduced to 10 per cent.

“The Taliban don’t know enough about all the procedures in various ministries yet, so these guys collect fees like they used to and tell their Taliban supervisors it is normal,” he said. “But they don’t squeeze so much out of you that you might go and complain to one of the mullahs.”

Mr bin Shah said that the Taliban’s return was an opportunity when it came to fighting corruption — one he thinks they are frittering away.

“We were given a clean slate last year [when the Taliban took over] … The superpowers were gone and for the first time in a long time the country had to deal with its affairs itself,” he said.

“For the first three months of the new government, I would receive regular reports from businesspeople that corruption was zero. But this is no longer the case, and it’s hard to say that no one from the Taliban is collaborating. For a time, you could say their ignorance was the problem, but until when? It has been a year.”

One evening in the first week of August, at a cafe in one of Kabul’s high-end hotels, The National overheard a western aid contractor suggesting to his managers back home that their organisation should consider paying off Taliban officials to get their job done easier.

They even suggested calling an old contact who used to enable similar payments in the republic days.

A pivot to new trade partners

While the US and others in the West are reluctant to do business with the Taliban, there are others less concerned.

China’s interest in Afghanistan’s much-vaunted but little-explored natural resources sector has excited many in the country.

Earlier this year, the Taliban government shook hands with Chinese businessmen to build the first “Chinatown” — a 10-storey shopping centre that hosts appliance shops and travel agencies.

Noor Rahman Ahmadi, 22, is one of 10 Afghans working there, alongside a few Chinese citizens.

He is fluent in Mandarin after spending four years at a Chinese university and he often works as an interpreter for Chinese businessmen.

Mr Ahmadi dreams of going back to China, but to do so, he would need to pay $1,400 to quarantine in a hotel for 10 days — an amount greater than his entire annual salary at Kabul’s Chinatown.

And this, critics of this new investment say, illustrates the problem experienced so far: many businesspeople have come to see Kabul, stores are being built and the mining sector appraised, but few are willing to invest in developing Afghan talent.

About 600,000 young Afghans enter the workforce every year, and the stagnant economy means few will find jobs.

And yet, in Kabul, cafes and shops are busy and it does not appear, at first glance, to be the capital of the world’s most impoverished nation.

But this, warns one aid worker, is an illusion.

“People are spending from their savings or remittances from family overseas, just so they can go out to eat like they used to,” he said. “Most people are not earning new dollars.”