The joy has been unconfined in the Palace of Westminster, in the studios of the BBC and in most of what used to be called Fleet Street at the tribulations besetting Rupert Murdoch. Day after day, fresh blows have landed on the shoulders of the octogenarian media tycoon, after his closing of Britain's best-selling journal, the News of the World, failed to contain the phone-hacking scandal.

Both his long-serving henchman Les Hinton and his Titian-haired protégé, Rebekah Brooks, have been forced out. His ambition for his son James to succeed him at the helm of News Corp, the Murdoch global empire of television stations, newspapers, publishers and film studios, seems, for the moment at least, to have been thwarted. The foundations of his holdings in the United States have been shaken as the US attorney general says he is willing to meet families of 9/11 victims concerned that their loved ones' phone records may have been targeted. Most ignominiously of all, Murdoch himself was attacked, during his testimony to a House of Commons select committee on Tuesday, by a foam pie-throwing comedian by the name of Jonnie Marbles.

Never again, it is said, will politicians have to grovel to the Sun King, nor his editors have to construct their papers' views around the commercial interests of this ruthless, beady-eyed, money-grabbing old Aussie. So loud have been the ululations from so many at his humbling, that it appears almost perverse to pose the question: why on earth did everyone take him quite so seriously in the first place?

Hold on, I hear you say: this is Rupert Murdoch we are talking about, confidant of prime ministers and presidents, the cynical hypocrite who saw no contradiction between his generosity to the Catholic Church - he was awarded a papal knighthood in 1998 - and his gifting Britain's Sun with the introduction of the topless Page 3 girl. But if all his awesome power can drain away this swiftly, why was he the object of such fear? Could it be, now his spell is broken, that those who were caught up in it must admit that his sorcery was an illusion, and only lasted because nobody dared challenge it?

I am not arguing that Murdoch was without sway. Authority accrues to the owner of any enterprise, whether or not they choose to use it as pugnaciously as Murdoch did in his showdown with the once-mighty British print unions during the 1980s. Possession of newspapers has long been regarded as a choice calling card by wealthy men - they are not known as press barons simply because in Britain most end up with peerages. But Murdoch was regarded differently. To him was attributed a uniquely diabolical quality, and especially by the left. The very phrase "the Murdoch press" was a shorthand for malign, twisted intent and a harsh, Thatcherite agenda that placed no value on gentler morality or tradition, and suggested that all who worked for his titles must be irrevocably compromised.

Yet where exactly is the evidence of the evil he supposedly perpetrated? For sure, the Sun and News of the World are (were, in the case of the now defunct NOTW) atrocious rags that revel in the misdeeds of "celebrities", coating their exclusives in sanctimony while playing to the prurient, salacious appetites of their readers; but they are far from alone in that, as a glance at the headlines of tabloids around the world will confirm. Neither, we can be certain, will the malpractices of hacking and police bribery ultimately be shown to be confined to Murdoch's titles.

What, then, of his upmarket papers, TheWall Street Journal, The Times and Sunday Times? True, accusations of proprietorial interference were levelled by Jonathan Mirsky, the former East Asia editor of The Times, who claimed that critical pieces on China were censored so that Murdoch could gain access to the country's pay TV markets (this was denied by the then editor, Peter Stothard); a similar charge raised by a former Middle East correspondent, Sam Kiley, was that his reports were amended if they were not sufficiently friendly towards Israel.

Such allegations, if true, may be deplorable, but they are hardly unknown. Papers have "lines" on many issues, and to pretend that their owners do not have any say on them is naive. It was perhaps to be expected that when I interviewed Robert Thomson, then editor of The Times, now managing editor of The Wall Street Journal, a few years ago, he batted away questions of interference from above. Listen instead, then, to the highly respected columnist Alice Miles, who wrote in the New Statesman last week: "Not once in a decade, including a couple of years as comment editor, was I influenced in what I wrote for The Times or what I commissioned. I never recognised the organisation that I worked for in the hysterical coverage about the 'Murdoch press' in the left-wing media."

If Murdoch was no better or worse as a meddling proprietor than, say, Conrad Black - who, as owner of titles in Canada, Britain and Jerusalem, refused to countenance any criticisms of Israel - or New York publishers of long ago, William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, who rattled sabres to start the Spanish-American War (talk about meddling), then where did the power that made Murdoch the object of such loathing lie?

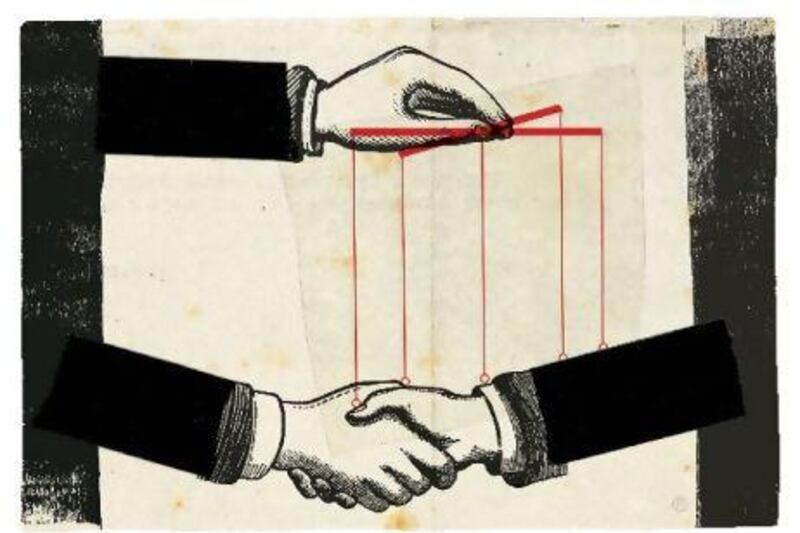

In politics, is the answer. And for that, I blame the politicians. Rupert Murdoch owned four British newspapers with a massive combined readership. Although psephological studies have concluded time and again that the impact of newspapers' endorsement of one particular party or another has little effect on readers' voting intentions, political strategists became convinced that they did.

The Sun's notorious front page at the end of the 1992 general election campaign - "If Kinnock wins today will the last person to leave Britain please turn out the lights" read the headline, with a picture of the Labour leader's head framed in a glowing bulb - was deemed to have been particularly influential. Actually, it wasn't. The election campaign was neck-and-neck but the electorate didn't trust the Welsh Windbag: all the paper was doing, as Murdoch publications have done consistently, was scent which way the breeze was blowing and react accordingly.

But then and now, that didn't stop politicians eagerly abasing themselves before the great Rupert. Both Tony Blair and David Cameron flew across the world to pay court to him after becoming leaders of their parties, not once stopping to consider whether that suited the dignity of their positions as presumed premiers-in-waiting. John Major ended up living in fear of what Murdoch's papers had in store for him. In 1992, Major even suffered the humiliation of being told by the Sun editor Kelvin MacKenzie that on his desk he had a big bucket of ordure (Mackenzie put it more crudely than that), "and tomorrow morning, John, I'm going to pour it all over your head". Major had, not long before, won a general election; Mackenzie, when all was said and done, was just a newspaper editor. But the prime minister did not respond in the robust Anglo-Saxon many might consider to have been appropriate. His pathetic reply? "Kelvin, you're such a wag."

It is not unreasonable for politicians to care what is printed about them. Neither is it unusual for them to try to cultivate media proprietors. Their prostration before Murdoch and his minions, however, reached horizontal positions previously reserved for ancient potentates. In doing so, they inflated this press magnate into a powerful ogre whose slightest whim they sought to satisfy and whose disfavour they so came to fear. In truth, he was no more than a goose to which for so long they were afraid to say "boo". There is something distasteful in their rejoicing at his fall. For he was, at least partly, a spectre of their own creation and collusion.

Sholto Byrnes is a contributing editor of the New Statesman