Belatedly people are beginning to find out just what a remarkable athlete – and man – James Willstrop is.

The belatedness does not reflect on him, but on squash, a sport that for reasons never deeply examined or satisfyingly articulated, has never cut it.

The game has deep traditions in many countries, Australia, England, Pakistan and Egypt lead among 135 nations that officially play.

It is not as broadcast-friendly as tennis – the small ball and speed makes tracking the action and its many subtleties difficult. But it still isn't a bad watch.

What it really needs is a slick spin doctor (though it is endearing they have not yet come across one) to turn exceptional athletes and their matches into the stars and their monumental rivalries you want to read about.

Instead the sport has been preoccupied for many years with becoming an Olympic event.

They have had great opportunities before; in Jahangir Khan they were briefly relevant (though that had as much to do with his management as squash authorities).

But if you think about the compelling characters squash has had – Geoff Hunt, Jonah Barrington, Amr Shabana, Jonathon Power, Hashim Khan to name an exact handful – and how little you know about them, then the game is failing, repeatedly, over many years.

In Willstrop lies another golden opportunity and at least he has done something about it himself.

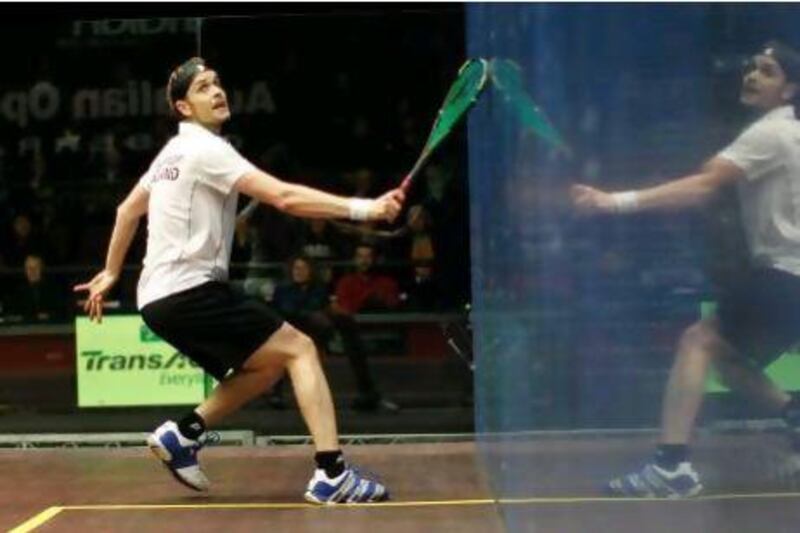

An Englishman, Willstrop is the current world No 1 but that seems barely adequate.

He has recently published what is essentially a diary – Shot and a Ghost – A year in the brutal world of professional squash – but is actually a grand and delicate gesture of self-revelation and introspection, on a scale few sports autobiographies can hope to imagine.

Willstrop, a Yorkshireman, is unceasingly human and if that sounds obvious, just remember how unreal sports stars really are.

He leaves nothing untouched, not tensions with his girlfriend (a former top-ranked player) on whether to have a child, his obsessive compulsive tendencies or the trauma of his mother's passing from cancer.

The relationship with his father-coach Malcolm is complex though not troubled. Many days he cannot be bothered to train, the prospect filling him with serious dread; his description of driving to training, passing the same signs, shops and pubs but mostly fearing the same impending pain is instantly relatable to anyone who has agonised over not wanting, for example, to go to the gym.

And those same people will recognise his subsequent eagerness to return to train after what he calls, frankly, periods of excessive indulgence. "One can only feel a slob for so long," he writes.

Willstrop stands considerably apart generally, but especially from the vast lump of sporting humanity, not just because he is a committed vegetarian, that he likes musicals or that his opinions on team spirit are stripped of cliche. It is because he is not a man to let life and its moments pass by without pause for deeper consideration.

Consider this simple, powerful take on the strangeness of success. "After winning events, I had always expected to feel immensely happy, and of course to a certain extent I do, but the immediate aftermath is really quite strange.

"After the photos and the cameras, the interviews and the people, the only obvious thing to do is retreat to the hotel, usually alone … I look at the trophy and the room and it is odd. I wonder what on earth I should be doing next."

Later, as he discusses the uselessness of bank holidays, he drifts into wondering how athletes are prone to obsessive compulsive tendencies, because of how their experiences swing from one extreme to another.

"Athlete's lives consist of great contrasts: from the hardest training sessions to hours in bed; large crowds to empty hotel rooms … There is such a gulf in the level of intensity that for some it can cause problems."

The word brutal often appears with squash. It is a brutal game, even when played among friends to no serious quality.

Minutes in and your brain stands shaken like little else; few sports make it so hard to unite mental faculty with physical agility simply because the disorientation is so acute.

So to read as humanising a line as this – "It continues to baffle me that, despite all my training over the years, this sport can still render me exhausted within 10 minutes" – is to be on almost personal terms with a man who is the very best.

There are not many athletes of which that can be said.

[ osamiuddin@thenational.ae ]

Follow us

[ @SprtNationalUAE ]