Following the French military intervention in Mali in January this year and the hostage crisis in Algeria that soon followed, major world powers briefly orientated their regional focus towards the Maghreb and Sahel region.

In the midst of the escalating conflict, pundits pointed to Morocco's geopolitical position as an ally of France and the United States and a source of stability. For example, in an opinion article in The New York Times, Anouar Boukhars, a non-resident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment's Middle East programme, argued that "Morocco has the will, the influence and the capability to contribute to conflict resolution in the region".

Conveniently omitted from this argument is Morocco's role in one of Africa's longest-lasting territorial disputes, in the Western Sahara.

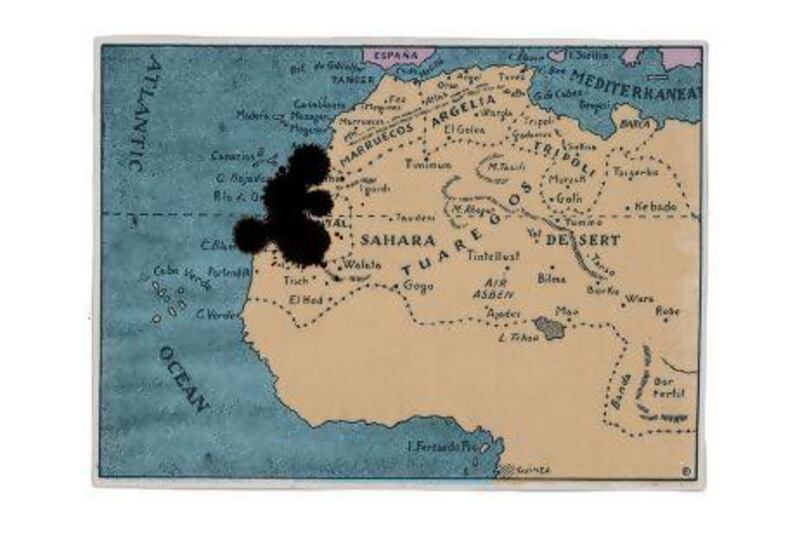

The Western Saharan conflict is arguably one of the world's most overlooked territorial disputes. Until 1976, the area was a colony of Spain and had been so since the end of the 19th century. But independence movements have a long history in the country, as do attempts by Morocco and Mauritania, two countries the region neighbours, to claim the territory.

Yet while the conflict results from colonialism, and continues to labour under that legacy, it took shape most profoundly during the Cold War.

In the early 1970s, Morocco - a friend and ally of the United States - squared-off against the Cuban-Algerian-Libyan backed Polisario Front, a national liberation rebel group fighting for an independent Western Sahara, which was indirectly armed by the Soviet Union.

King Hassan II of Morocco well understood the dynamics of the Cold War logic driving American foreign policy decision-making, and he used it to his advantage when appealing to the United States for military and financial support against the Polisario Front. The king argued successfully to the Reagan administration that the Western Saharan conflict was a "Cold War conflict".

This would begin to mark the nature in which the conflict would be discussed and used for political means, while disregarding the very dire humanitarian situation neglected by both sides in this debate.

Today, the debate surrounding the Western Saharan conflict has moved away from the old Cold War framework and has been refashioned to fit the rhetoric associated with the "War on Terror". On numerous occasions, supporters of Moroccan claims to the territory have drawn explicit links between the conflict, the Polisario Front and Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (Aqim).

In a 2009 letter addressed to the US president, Barack Obama, and signed by more than 200 Congressional representatives, House members argued that the "single greatest obstacle impeding the security cooperation necessary to combat" Aqim is the Western Saharan conflict. More broadly, claims without much detail or explanation to "the curious relationships between the Polisario Front and Aqim" have become rampant. Within roughly 30 years, the Polisario Front has gone from being a Soviet-ally and "communist separatist group" to a friend of an Al Qaeda affiliate.

Moroccan law has integrated the Western Saharan debate into its constitution, whereby any criticisms of its policies towards the Western Sahara can be easily interpreted as a threat to its "territorial integrity".

At the same time, the Polisario Front and its supporters have done their own share of information manipulation in an attempt to drum up support against Morocco. The most remarkable was an incident in which a photograph taken in Gaza was miscaptioned and printed in multiple publications claiming it was taken in Laayoune, Western Sahara's largest city.

Through these instances and others, the discussion and debate surrounding the Western Saharan conflict has become severely skewed and misrepresented on all sides.

The Sahrawis, who are living in deplorable conditions and suffering a brutal denial of basic human rights, continue to pay the price of a debate that ignores them and their struggle for dignity and self-determination.

With Morocco historically receiving multimillion-dollar military and financial aid packages, especially from Saudi Arabia, to combat the Polisario Front, the discourse surrounding the conflict reflects entrenched regional power interests.

Aside from Algeria's support of the Polisario Front, which has more or less remained consistent since the beginning of the conflict, no Arab government has directly challenged Morocco's claims to the territory.

However, that has changed in the past two years, in the context of the continuing crisis in Syria. Discussion of the conflict is being revived for propaganda purposes.

Morocco has steadfastly expressed opposition to the Syrian regime, whether by hosting regional meetings or by expelling the Syrian ambassador to Rabat. In response, a video was circulated on YouTube showing Syria's ambassador to the United Nations, Bashar Ja'afari, addressing Morocco by asking: "Do you want us to open up the case of the Western Sahara?" Mr Ja'afari goes on to bring attention to "the people of the Western Sahara demanding their rights".

Perhaps sensing that a Syrian government official is hardly in a moral position to advocate for human rights, the Polisario Front's mouthpiece, the Sahara Press Service, did not publish any press release or comment regarding the Syrian official's support. That did not stop the Moroccan press, however, from interpreting the statement as "Bashar Al Assad embracing Western Saharan separatists".

Regardless, it is very clear that as in previous instances, the Western Saharan conflict is being invoked in this situation not out of any genuine concern for the welfare of the Sahrawi people, but instead to score political points in a crisis thousands of miles away.

Despite evidence detailing the dire humanitarian situation on the ground, the discussion about Western Sahara continues to be diverted elsewhere. In August of last year, the Robert F Kennedy Centre for Justice and Human Rights documented its trip to the territory. A post written for The Huffington Post by Kerry Kennedy, the centre's president, provided a detailed account, along with images, of a Moroccan officer beating a Sahrawi woman, Soukaina Jed Ahlou, who had been peacefully protesting.

The images show the woman protesting, and then lying down with a bloodied face. In numerous articles published in the Moroccan press, the centre's neutrality on the conflict was challenged, with state media saying the Kennedy delegation was "keen to meet the Polisario puppets".

In no instance was the simple fact that the delegation documented the brutalisation of Soukaina Jed Ahlou even mentioned. It was as if the images of her bloodied face were entirely nonexistent or that they were somehow less significant than the business of contriving theories for partisan gain. The message: it is the politics that matter, not the abuse of civilians in Western Sahara.

The need for greater international attention to the Western Saharan conflict, and more particularly the abuses suffered by the Sahrawi people, could not be clearer. Even in instances where the platform is provided, such as the recent World Social Forum in Tunisia where the Moroccan delegation verbally and physically intimidated Sahrawi activists, the focus centres on the political confrontation rather than the greater struggle for human rights.

Tragically, what little attention it does receive is all too often intended only to smear political parties or peddle propaganda, leaving the muffled voices in the territory to bear the terrible cost of neglect.

Finding a resolution to the Western Sahara crisis demands deviating away from the dominant narrative propagated by the regional powers, which has come to shape policy, and ensuring that the voices of Sahrawis are not only included in the discussion of their future, but more importantly become the central voices in this debate.

Samia Errazzouki is a Moroccan-American writer based in Washington DC

On Twitter: @charquaouia