The three year civil war in Syria has highlighted the contraction of American influence in the Middle East, now an undeniable characteristic of the political landscape here.

Washington’s waning influence in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Pakistan, Iraq, Afghanistan, Palestine and other countries is partly due to the increasing independence and assertiveness of the players themselves. It is also the result of traditional balance-of-power politics by insurgent regional adversaries, such as Iran. Finally, it is due to the internal facts of the American presidency – its lobbyists, bureaucrats and the personality of the president himself.

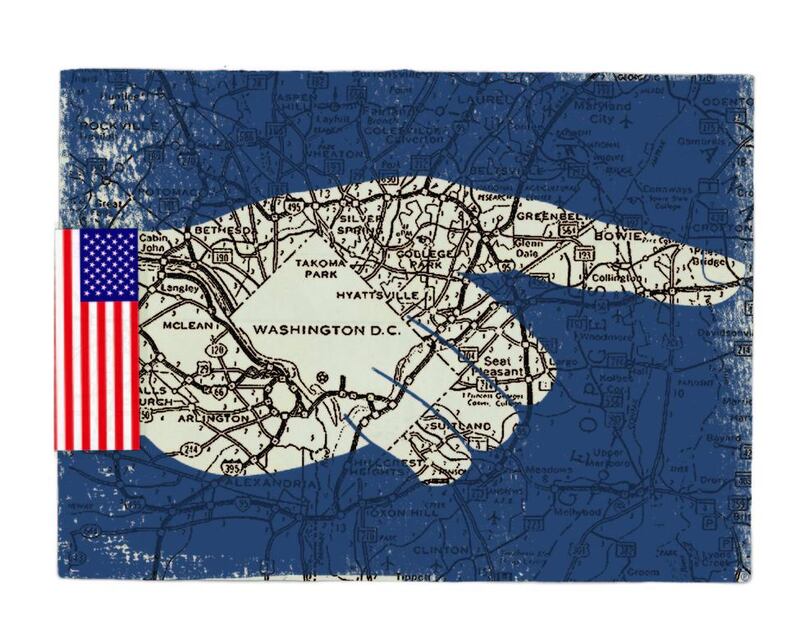

American policy in the Middle East has developed at the juncture where geopolitical and domestic forces meet in the Oval Office. Among senior American officials a new awareness that events may overtake policymakers in Washington – as in Benghazi for instance – has produced a reticence to intercede.

That reticence is also the result of a newly constrained view of American power. The path of Washington’s imperial trajectory has rounded its apex – it is now on its way back to Earth. Notably, that more realistic view of American power may produce an accord with Iran, particularly as the president seeks to firm up his foreign policy legacy.

Presidential historians credibly claim that the American president both shapes and is shaped by the office he occupies. The manner in which the evolution occurs is both personal and due to local and international developments.

Consciously or otherwise, the president telegraphs his views, biases, and inclinations through his advisers and staff into the far reaches of the foreign policy apparatus.

Every node in the network – nearly every individual charged with implementing some aspect of policy – interprets his or her job through the greater or lesser focus of the presidential prism. The relationship is stronger among political appointees and members of their staff, but it also exists among career bureaucrats. In turn, the bureaucracy, its codes and standard operating procedures, carves the deep channels that constrain or direct presidential prerogative.

It may be hard to remember now, but 15 years ago George W Bush communicated a notably constrained foreign policy vision as contender for the Republican Party nomination. He claimed to believe that nation-building was an exercise in futility and the outcome of bad judgment, an implicit condemnation of his predecessor’s policies in the Balkans.

Yet, nine months into the Bush presidency, Al Qaeda attacked New York. The terror attacks precipitated a change in policy, but that change was also shaped by a human, bureaucratic legacy of imperial involvement and broad national receptivity to violence. Other countries, for example Spain after the 2004 Madrid bombings, may have chosen to disengage with the Middle East after an attack. Bush, and Americans, chose to wage war in several countries. It is worth noting the fact that national preferences change – Americans today are far less receptive to arguments for war than they were in the days and months following September 11, 2001.

Like many presidents before him, Obama’s understandable drive to achieve real and durable change impacts his view of priorities and opportunities.

People recall Lyndon Johnson’s role in Vietnam but he also worked to close the civil rights gap in America – his is a mixed legacy. Barack Obama implemented a major set of health-care reforms, and reduced the number of Americans in Iraq and Afghanistan, but he has not yet achieved a positive – as opposed to reactive – foreign-policy goal that may contribute to his presidential legacy.

And that’s a critical point– that the difference between active policy engagements and the resolution of policy failures is a meaningful one. It is easier to remember Johnson’s role in the ultimate defeat in Vietnam than it is to remember who withdrew the last troops in that failed war.

When he first came to office, Obama demonstrated an ambitious willingness to address substantial foreign policy challenges. He aimed to provide a path to a Palestinian-Israeli accord. He pledged to close Guantanamo Bay and to forge a new relationship with the Arab and Muslim world, one based on mutual respect and security. He voiced a willingness to re-examine ties with Iran. Real movement on any of the three would have produced a meaningful legacy.

Regrettably, this policy agenda was encumbered by internal opposition and external events – and in many cases the US president failed to overcome those challenges. His failure was due in some part to his personal shortcomings – like his dogged insistence on bipartisan agreement with a reluctant Republican party, but it was also because of entrenched domestic lobbyists. Obama also faced increasingly assertive global adversaries and real resource constraints owing to a recession and a trillion-dollar Afghanistan/Iraq war bill.

In the case of Palestine, Obama began his first term by highlighting the illegality of Israel’s colonisation of the occupied territories – a longtime American position on the issue. He spent a great deal of personal credibility when he proclaimed his position in Cairo among people who were listening closely. Yet opportunistic legislators with a deferential relationship to members of the Israel Lobby quickly undermined the president. He retreated from his policy goal in Palestine after acknowledging the domestic constraints he faced on issues related to Israel.

And then, in 2011, the Arab revolutions began. As the largest supplier of military aid and political support to the Egyptian government, the US was widely perceived as having a special responsibility to the Egyptian people.

Obama was faced with an unpalatable choice – push for democracy or preserve a long-time American client. He dithered for weeks before finally backing the revolutionaries. His indecisiveness – or more charitably, his wait-and-see tactic – would later come to define his approach to unrest in Libya and Syria.

While prudent from a capacity perspective – Egyptians made it clear that American influence was limited – Obama’s decision to “lead from behind,” the dominant strategy in Libya, is hardly the kind of legacy-affirming leadership he would needed to shape a grand, positive foreign policy legacy.

Failure on Palestine left Obama with one major foreign policy challenge around which he could craft a meaningful legacy. The relationship with Iran was a difficult one following the 1979 revolution, and it worsened after George W Bush issued his infamous “Axis of Evil” speech in 2002. But a confluence of local and international developments provided the opening that the president needed to begin to move on his long-standing Iran policy goal.

First, a war-weary American people exhibited a greater degree of receptivity to a diplomatic resolution of Iran’s nuclear programme. At the same time, a change in the Iranian leadership enabled the president to make a credible case for engagement among his diplomats and other world leaders.

Finally, as a second-term president approaching the second half of his final term, Obama has little time to achieve any major policy goal whose implementation is not already under way.

For those reasons, in an American era defined by resource constraints and risk-averseness, diplomacy in Iran appears to be the likeliest option. The office of the US president and America’s public mood are both affected by the personality of the president. But they also influence, to a surprising degree, exactly what he is ultimately able to achieve.

Ahmed Moor is a Palestinian-American writer who was born in the Gaza Strip. He is a Soros Fellow, co-editor of After Zionism, and co-founder and CEO of liwwa.com

On Twitter: @ahmedmoor