SANA'A // The insurgency smouldering in Yemen's north, the secessionist movement gaining momentum in the south and fears of al Qa'eda sanctuaries are, analysts say, the symptoms of growing disillusionment among Yemenis with party politics, which are dominated by a powerful president and an ineffective opposition.

Although functioning in what can at times be a relatively free political environment, Yemen's opposition parties have struggled to carve out coherent platforms and have regularly succumbed to Ali Abdullah Saleh's enticing patronage. But for people who have waited years for reform, such failures have instead yielded, if not contempt for rampant corruption, apathy, says Ali Saif Hassan, the executive director of Political Development Forum, a research organisation based in Sana'a, the capital.

"The parties have no roots among the people," he said. "They operate more like lobbyists, asking for government favours for this and that, but in the process they are killing themselves because they lack loyalty." For the past decade, party politics have been dominated by the General People's Congress, a firm ally of Mr Saleh, and an unlikely opposition coalition of Islamist, tribal-based and socialist parties known as the the Joint Meeting Parties (JMP). It has been a relationship characterised by stalemate and inaction: allegiances have routinely shifted between the government and the opposition, and flimsy alliances have been forged between parties with seemingly diametrically opposed ideologies.

Parliament, at the moment, is again gridlocked, this time over issues stemming from last year's postponed parliamentary elections. But for people such as Nashir Abdulelah, 43, whose small shop is next to the adobe barrier of Yemen's fortress-like parliament, in the Midan Tahrir, it is best not to waste time thinking about things he says will never change. He instead concentrates on how to feed his four children, since incoming customers, especially tourists, have dropped off.

"What can the opposition do inside that building?" said Mr Abdulelah, pointing to parliament as government troops swarmed nearby, like they do nearly every day, with semi-automatic weapons. "It's all under government control anyway." It is this sort of apathy, Mr Hassan said, that explains why "the most popular movements in Yemen have become the Houthis [Shiite rebels], the secessionists in the south, al Qa'eda - because they are addressing the people; they live among them, and they have a simple message".

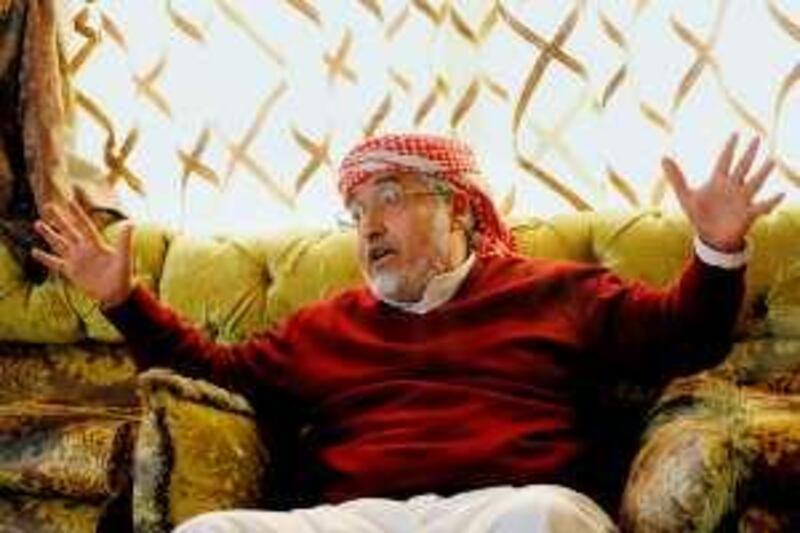

He and others described parliamentary politics in Yemen as more about finding one's spoils in a Byzantine patronage network, through which elites dole out "incentives" to opponents and promote family members. That system largely centres on Mr Saleh, whose deft politicking over the past 32 years has helped him exploit differences in opposition parties and prevent the emergence of potential challengers. "He's not only smarter than his competitors," Mr Hassan said, "he's a very hard worker who uses all of his tools available to him to his advantage."

His skilful manoeuvring has turned foe into friends and friends into obedient allies. Prominent tribal sheikhs, for example, have been known to unabashedly endorse his re-election bids in return for rewards, even though their own party supported a different candidate. Some members of the opposition coalition's most influential party, the Islamist Congregation for Reform, or Islah, openly flaunt their relations with him, such as Abdul Majeed al Zindani, a hardline Salafist whose private university recently received a new paved road courtesy of the government.

Still, amid the crises, some see glimmers of potential opportunity. Revenues from oil exports, which form the bulk of the national budget, have plunged, and many are wondering whether Mr Saleh can maintain his patronage framework. The opposition, particularly Islah, could use this moment to push upon the president's weakened government its agenda of democratic reforms, said Sarah Philips, an independent Australian scholar on Yemeni politics, said. "This could be their moment to make an incredible inroad.

"But that's not the way they want to play," she said. "They think it's too confrontational, but they're missing opportunities, and I'm looking at it as why, when there is such a threat to the country, these smart, capable guys haven't been able to come together." Senior JMP members, however, defend their stance, saying the collective power of the coalition far outweighs what they could muster individually.

"We think that as an opposition movement, we have succeeded in staying away from narrow party goals, " said Mohammed Kahtan, a ranking member of Islah, which is a religiously conservative and powerful party in the JMP. Deviating from the coalition's goals of peaceful but seemingly passive dialogue, such as pursuing a populist-style politics, not unlike that of their Muslim Brotherhood counterparts in Egypt and Jordan, could scupper their agenda of democratic reform, he said. "If we get people mobilised, what will be the outcome if we can't produce solutions? This is why we're trying to build consensus, so we can build a realistic platform."

Mohammed al Sabri, a senior figure in the JMP's Nasserite Unionists, a secular party, worried that confronting the government with organised, peaceful demonstrations could produce violence or worse. Rights groups have decried what they say is the government's increasingly heavy-handed tactics, which, perhaps because of sensitivity to its own weaknesses, include jailing and torturing journalists. "The [ruling] government is not the only one who is weak - the state itself is weak," Mr Sabri said. "What will civil disobedience lead to? We have sectarian divisions here, growing separatism in the south."

In some respects, said Amr Hamzawy, an expert on Islah and a senior associate at the Carnegie Middle East Centre, a policy think tank in Beirut, that sort of disintegration might in fact be already happening, but within the opposition coalition itself. As secessionist sentiment in the south rises, the strength of Islah's relationship with the Yemeni Socialist Party, its main coalition partner in the JMP, has been suffering. The two were enemies during the 1994 civil war, then later found common ground, but are now struggling to define their relationship as the secessionists gain momentum.

"Co-operation between Islah and the Socialist Party is really starting to fade. Clearly the two are being driven apart, and it makes sense," Mr Hamzawy said. "The Socialist Party is more concerned with what's going on in the south ? but Islah has been silent on what's going on down there." These kinds of internal divisions are starting to concern the General People's Congress, particularly in negotiations over parliamentary elections scheduled for next year, said Mohamed Qubaty, the congress's chairman of foreign relations affairs and international department.

"We appreciate the formation of the JMP, but we do hope they will soon decide on a unified platform so we can get on with things," he said. @Email:hnaylor@thenational.ae