Bang on your scheduled arrival time, you are in the airport. How perfect is that? Unfortunately, the airport is the one you were hoping to depart from. Everywhere around you, wreathed in the noxious whiff of junk food and rage-induced perspiration, swarm your fellow passengers, all of you trapped in a vast, inhuman holding pattern. Once on board, that big, comfy seat they tempted you with in the brochures turns out not to be quite so comfy. Partly because the man seated next to you is the size of a plesiosaur. And the woman on the other side is clutching three-month-old twins, either one of whom could drown out a Metallica concert. You squeeze in to the sliver of space between them, watch idly as miles of greasy tarmac slide by on your crawl to the runway, and prepare to grapple with the world's most depressing question: chicken or beef?

Whatever happened to the glamour of airline travel? To the discreet tinkle of piano lounges, the sipping of expertly shaken cocktails, the adjustment of silk cravats? Modern air travel has become a nightmare. One that is likely only to get worse, and as the memories of the good times fade, a whole generation of air travellers is growing up hardened to the everyday humiliations, delays, discomforts and rip-offs of flying.

The problem isn't merely that airports have become vast, fortified shopping malls filled with chain outlets and awash with slobs in shell-suits. Or that the process of getting to the plane routinely takes longer than the actual flight. Or even that the on-board experience is ... well, the author Thomas Harris describes it with appropriate distaste in his novel Hannibal: "Shoulder room is 20 inches. Hip room between armrests is 20 inches. This is two inches more space than a slave had on the Middle Passage. The passengers are being slopped freezing-cold sandwiches of slippery meat and processed cheese, and re-breathing the f**ts and exhalations of others in reprocessed air."

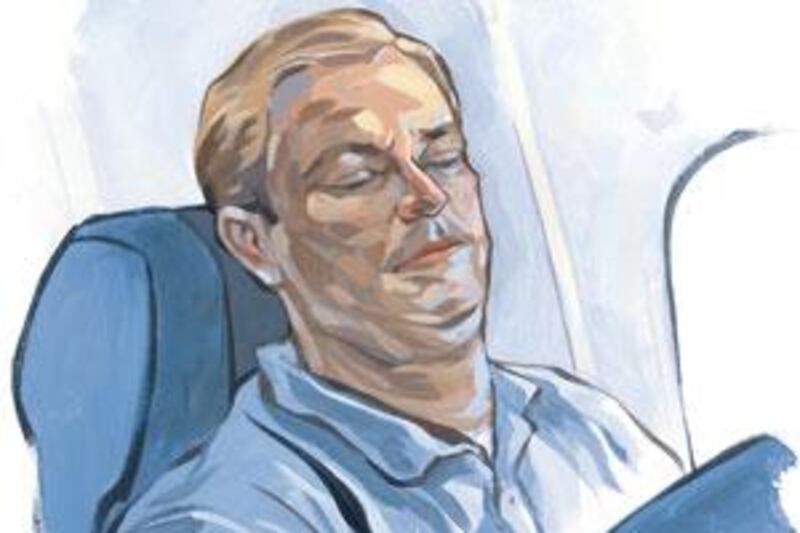

Today's airline traveller knows that all this awaits him. If he doesn't, a tuned-for-maximum annoyance system of check-ins, passport control, security scans and boarding gate hold-ups serves to constantly remind him. Yet, what really baffles him as he stands and shuffles, nose to the immobile back of the passenger in front, is how these horrors came to be visited upon him. The answers are complex and reflect, to a great extent, both the best and worst of human nature.

Flying was, indeed, once glamorous. In the mid-1940s only around 10 million people took commercial flights, and international routes barely existed. To fly at all was to experience something of exotic rarity. Today the number of airline tickets sold each year approaches three billion, and at any given moment more than 750,000 people - roughly half the population of Abu Dhabi - are up there in the sky.

In the course of getting to its current oversubscribed state, air travel has shed more than glamour. It has lost its essential mystique - the sense of wonder we used to have that it was actually possible to fly, and that human ingenuity had built a craft capable of such a thing. This almost childlike appreciation made flying - at least in the early days - something akin to the witnessing of a miracle. Today's airline passenger barely realises that he's doing something that all earlier generations of humans would have considered pure fantasy. In Virgin's Upper Class cabin the seats are configured herringbone-fashion facing the centre. The message is obvious: only nerds want to look out of the window.

For the first few decades of commercial air travel the glamour lingered because the fantasy remained essentially intact. Flying was the privilege not just of the few, but of the few in possession of both money and a spirit of adventure. During the 1930s and 1940s, the great Pan Am Clippers plied the skies, crewed by men in starched naval uniforms and attended by women in pale blue dresses and pink lipstick. Furnished in the manner of flying gentlemen's clubs (an early brochure lists dining tables of black walnut, Wedgwood china and soft leather seats) these majestic machines first opened up the world to the idea of international travel. In doing so, they set us on a course to today's degradations.

In the early days there was only one class - expensive. A return ticket from San Francisco to Shanghai on a Clipper cost $12,000 at today's prices, but aviation technology was developing fast and by the 1950s and 1960s new planes such as the Boeing 707 and the De Havilland Comet became the flagships of the Jet Age. They were fast, efficient and offered the tantalising whiff of air travel for all. Still the sense of wonder endured. "It was actually more than that," says the former British Airways stewardess Libbie Escolme-Schmidt, author of the recently released book Glamour in the Skies. "There was an atmosphere of optimism and possibility and tremendous excitement. Passengers would dress in their best clothes for the flight. Many had never been aboard an aircraft before.

"Stewardesses were treated like celebrities. We went to official functions, stayed at the finest hotels. Every girl dreamed of being a stewardess. I remember going for a job interview, and there were all these immaculately turned out, beautifully spoken young ladies flicking through Vogue and Tatler. All desperate to be pushing trolleys." Pilots, for their part, assumed the image of the cool-nerved hero. Steven Spielberg's 2003 movie Catch Me If You Can wittily evokes the romantic heyday of air travel. It tells the story of a con-man impersonating a Pan Am pilot, raising the question of who better to impersonate if you want a good life?

Yet, as the Golden Age of air travel came to an end, the signs of turbulence were already looming. Aviation's attractions were driving its popularity faster than anyone had imagined. "Come Fly With Me", crooned Frank Sinatra, and millions took up the offer. Airports - most of which had been built on the lines of municipal bus stations - could no longer cope with the onslaught of passengers. Slowly it became clear that the airline pioneers' dream of free movement of people could only be achieved by a global system of mass transportation.

This was the world the air traveller had progressed to by the 1970s. The glamour had largely gone, but, by way of compensation, the traveller found that flying was a convenient and not unpleasurable way to get around. He could buy a ticket without having to show identification, check his bags without being interrogated as to their contents, walk unimpeded through the airport and have a good chance of finding an uncrowded plane. It was cheaper, too. Deregulation of the United States airline industry triggered a global trend for new, nimbler airlines that paved the way for today's low-cost carriers.

A new image of the air traveller evolved from the upheaval. No longer did he resemble Humphrey Bogart escorting Ingrid Bergman to a spluttering Lockheed Electra in Casablanca. He flew because it was practical and his time - or his employer's time - was valuable. But by turning aviation into a utility, he brought about the end of an age of innocence. By the 1970s, the realisation was dawning that, beyond its usefulness in moving people around the world, an aircraft could, potentially, be a useful tool of criminal or terrorist enterprise. Between 1969 and 1978 there were more than 400 international hijackings. In response, governments turned airports into high-security zones.

"Air transport," says Michael O'Leary, the boisterous boss of Europe's biggest budget airline Ryanair, "is just a glorified bus operation." He isn't far wrong. Modern pilots are essentially computer operators, and passengers have become a bulk commodity to be freighted around the world at the lowest possible cost and highest possible margin. There are, to be fair, exceptions. The UAE's national airline, Etihad, last month won the top award at the World Travel Awards for its high standards of service.

But the pressures on the traveller continue to grow. Under the guise of environmental concern, governments now use him as a cash cow - imposing taxes that can exceed the cost of the ticket. Airport operators, who make much of their profits from retail operations, have little incentive to speed him past their glitzy malls. The glamour isn't coming back. You can still - if you want to spend the money - fly in luxury. But the real magic came from exclusivity, and that has gone forever.

The loss should be tempered by the knowledge that the urge to travel, to explore, to discover, has driven human progress throughout history, and that the ordeal the traveller now endures demonstrates both the suffering and the power of the people. * The National