The hammour of the Arabian Gulf and the North Sea cod have an unenviable thing in common. They are both down to around three per cent of their former abundance and rank among the third of the world's fish stocks that scientists consider to have collapsed. If the Arabian Gulf or the North Sea fell within United States jurisdiction, they would be declared fisheries disaster areas and spawning areas, and vital habitat would be closed by law to commercial fishing.

But neither the North Sea nor the Arabian Gulf is managed in the cutting-edge way that the United States now manages some of its domestic fisheries - which has come about as a result of a healthy enthusiasm among environmental bodies for using the law to sue the authorities. (The other side of the coin is that 70 per cent of fish the US now consumes is from fisheries around the world, many of them unsustainable. Ditto the EU.) We in Europe and the Middle East go on hoping that something will turn up, that nature will somehow solve the problem, while doing rather less than is needed to bring about recovery.

We are beginning to realise that what we used to think of as a local problem, overfishing, is actually a global problem - and that we need to think globally and act locally to solve the problem of the oceans. For fishing, not pollution, is currently the principal destructive force across 70 per cent of the planet's surface. And the state of the world's fisheries is more disturbing than many people realise.

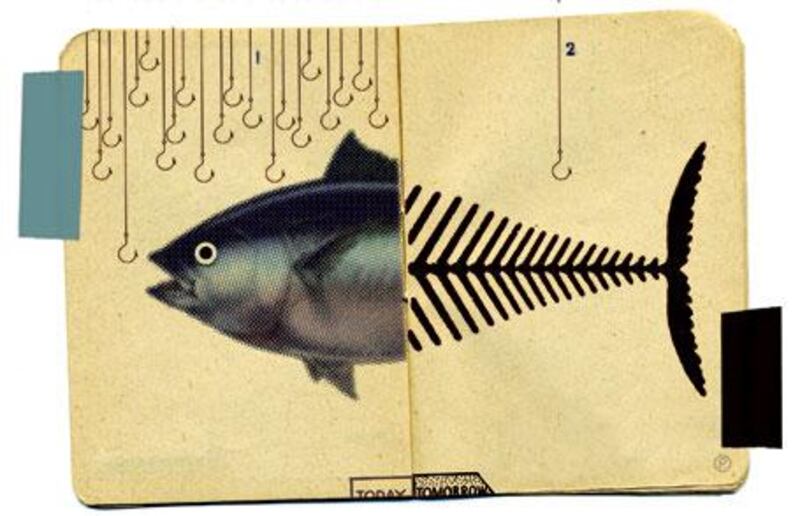

Currently, some 80 per cent of the world's wild fish stocks are either fully or over-exploited, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation. Ninety per cent of the world's large predatory fishes, such as cod, tuna and hammour or grouper, have gone - which means been eaten - since 1950. The majestic bluefin tuna in the Mediterranean is collapsing as I write, a story bound to take its place in the history of human stupidity and greed beside the blue whale and the Northern cod.

Now, if we go on hammering the sea as we have before, scientists are warning that we shall have collapsed the rest of the world's commercial fisheries by some time in the middle decades of this century - to roughly the same level as the hammour and the North Sea cod. That is a disturbing prospect since in the same period the human population of the planet is expected to rise by a half. In all the concern last year about food security, there was little talk of fish. But, thanks to some marvellous detective work which ironed out distortions in the official figures by Daniel Pauly and Reg Watson in 2001, we now know that catches of wild fish peaked in 1988 and have since been in decline. People talk about when we shall reach Peak Oil - the year oil production peaks and then begins to tail off. We already know that Peak Wild Fish was in 1988. In respect of wild fish, we have reached what the Club of Rome in the 1970s called a limit to growth.

You may well ask whether it matters that we have already reached the limits of wild fish, when we reached the limits of what food wild animals on land could provide us with tens of thousands of years ago. The human race now eats more fish than it has ever done: nearly half of it farmed. Won't fish farming take up the slack? Won't there be a Sea Green Revolution, and everything will be all right? I wish I were that confident.

The problem with fish farming as it is practised in the rich countries of the world is that it is largely the farming of carnivorous fish. To feed these carnivorous fish, vastly greater numbers of small fish - Peruvian anchovy, capelin, blue whiting and sand eel - need to be rounded up in small-mesh nets, often with a by-catch of the juveniles of other species, and ground up for fishmeal. The reality is that we have reached the buffers as far as the amount of small fish the oceans can provide and many of these stocks are already overfished. The North Sea sand eel, the base of the entire food chain for birds, sea mammals and fish has collapsed.

Catches are now around 100,000 tonnes not the one million tonnes once seen. The blue whiting is collapsing because the EU, Iceland and Norway are taking twice as much as scientists say they should to feed their fish farming industries. There are disturbing inequalities opening up in the world between countries that benefit from the farmed salmon and the countries that export the small fish. Globally, aquaculture figures show that the conversion rate between Peruvian anchoveta and farmed salmon is 5:1 not 3:1 as the fish farmers have long been telling us. If fish farming is this wasteful, wouldn't it be fairer to our fellow man to eat the little fish instead?

That is perhaps the most revolutionary thing said by our film about global overfishing, The End of the Line, which had its premiere in January at the Sundance Film Festival in Utah. Perhaps that is why some people have renamed it, with apologies to Al Gore, An Unappetising Truth. The aquaculture industry has two options if it wants to grow - produce synthetic feed or farm vegetarian fish. The first it has been much slower to do than it promised. It isn't hard to see why: fish have been eating other fish for billions of years, so they aren't going to take to grain that easily, at least not without ending up tasting of tofu.

Farming vegetarian fish is what the Chinese - the world leaders in aquaculture - have done so successfully and that is something the rest of us need to learn fast. Scientists suspect, though, that the Chinese have overstated how good they are at growing carp and tilapia. Remember the global wild fish statistics were proved wrong? That is because Chinese Communist officials were misreporting catches to get promoted. There is no reason to suppose they haven't been doing the same with aquaculture statistics.

So I think we would be wiser to recognise that we need healthy oceans and wild fish if we are going to feed ourselves. But we don't just need healthy oceans for that. We need them for recreation, for diving, for angling, for wildlife and for the general sense that flourishing ecosystems are being looked after. And we need them for one other gigantic reason, which we never knew about before. We may long have suspected it, but on Jan 16 this year, the journal Science reported a connection between overfishing and global warming.

Apparently it is the droppings of bony fish that keep the surface layers of the ocean alkaline and absorbing carbon dioxide. Healthy fish populations, it seems, make the planet healthier. No doubt this piece of science will be argued about further, but its significance is clear: we have underestimated the importance of healthy oceans to the human future. And if we are going to have healthy oceans we need three things: we need, as consumers, to eat only sustainable fish, to give a signal to the market. We need to cut the fishing fleet and observe sound science in managing fish stocks so that cod and hammour can actually recover. And we need to fence off large areas of the sea which are off-limits to commercial fishing so the productivity of the fish there can reseed other areas. If we do all this, we can face the new century with confidence. If we don't, I think our children are unlikely to forgive us.

Charles Clover is an award-winning journalist and author of he End of the Line, on which the new documentary is based. His previous book, Highgrove: Portrait of an Estate, was co-written with the Prince of Wales. He was environment editor of The Daily Telegraph in London for 20 years. To find or request screenings of the film, visit www.endoftheline.com