If the UAE pavilion at this summer’s 15th Venice International Architecture Biennale lives up to its curator’s expectations, it will be exceptional, but not in the way that many visitors might expect.

There will be no place for record-breaking skyscrapers, improbable feats of engineering, “starchitects” or the kind of mega projects that have helped to secure the UAE’s place in the popular imagination.

Words such as luxury and iconic will also be notable by their absence.

Instead, the architect Yasser Elsheshtawy has decided to focus on a seemingly more mundane episode in the UAE’s architectural history.

A widely published expert on urbanism in the Arabian Gulf and an associate professor of architecture at the United Arab Emirates University (UAEU) in Al Ain, he is looking at the development of the early generations of “Sha’abi” or low-cost housing that helped to transform the daily lives of generations of Emiratis in the late 1960s and 1970s by providing them with modern homes and amenities for the first time.

It is not the first time that the programme has attracted the interest of architects.

In 1977, the Architectural Review in London ran a special issue on architecture in the UAE that investigated Sheikh Zayed’s efforts to provide housing to a population that, in certain areas, was still partially transient.

Focusing on modern developements in Al Ain and Masafi, the feature was titled “Settling the Bedouin”.

Prof Elsheshtawy hopes that by focusing on the Sha’abi housing this year’s UAE national pavilion will allow visitors to the Biennale to move beyond the cliches that persist about life in the UAE.

“We would like to show the diversity of the architectural and urban landscape of the Emirates and to show people that it isn’t just about iconic buildings and skyscrapers and shopping malls,” he explains.

“There are some very interesting architectural experiments happening here where people are actively involved in constructing the built environment, and we believe the results could be useful for other cities and places around the world.”

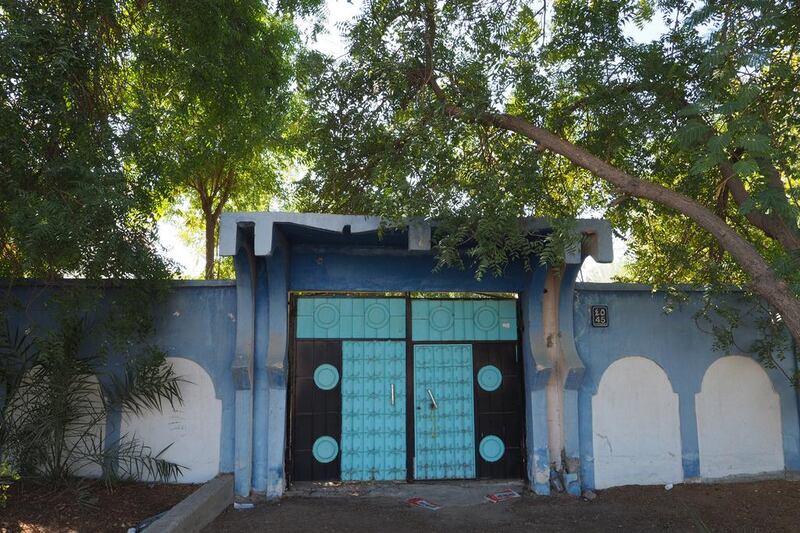

Built mostly as concrete, single-storey houses whose design was inspired by the arish, or traditional palm-frond architecture they were built to replace, they display a sensitivity to their users and a sense of place that Prof Elsheshtawy finds impressive.

“When you look at the early aerial images of Abu Dhabi, you can see the basic arish houses which form a basic enclosure with a courtyard and a bunch of rooms along the edge. And it is quite remarkable how that same basic model was used for the Sha’abi houses,” he says.

“They follow the same principle of a courtyard with rooms arranged around the edge, but this time it’s modular and it’s arranged on a grid. It’s clearly based on very specific requirements for certain rooms and the need for an open space and, of course, the need for the separation of the male and female, the public and the private areas of the house.

“They had electricity and running water but there was no air conditioning. In some [homes] you see a stairway that leads to the roof and it’s said that was used by the early residents as a place to sleep in the hot summer months.”

As oil revenues flowed and families became increasingly prosperous, Emiratis often left their Sha’abi houses in favour of larger, more modern residences. Many of the original developments, or Sha’abiyat, were rented out to foreign labourers or even demolished.

But a surprising number can still be seen in traditional neighbourhoods such as Falaj Al Mu’alla in Umm Al Quwain, Dhaid in Ras Al Khaimah, Bahia, Shahama and Baniyas in Abu Dhabi, and Sha’abiyat Al Shorta on the border between Sharjah and Dubai.

“In Dubai, Emiratis have largely left their Sha’abi houses and they are now occupied by South Asian workers and other residents. But in Al Ain and even in Abu Dhabi, a sizable number of Sha’abi houses are still occupied by Emirati families, particularly in the Al Difaa and Al Maqam neighbourhoods in Al Ain,” says Prof Elsheshtawy, who has been lecturing at UAEU and researching the architecture and urbanism of the emirates since 1997.

“Some houses are occupied by the older generation, people who simply refuse to move out. But others are occupied by families with multiple generations and inside these you get a fascinating mix of people and that is our focus,” he says.

Prof Elsheshtawy has been interested in Sha’abi housing for some time but admits that his decision to focus on the subject was more immediately influenced by the appointment of the Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena as curator of this year’s exhibition and Mr Aravena’s decision to make “Reporting from the Front” this year’s theme.

The founder of Elemental, the architecture practice he set up in 2001 with the engineer Andres Iacobelli, Mr Aravena is most famous for his work on low-cost social housing schemes such as Quinta Monroy in Iquique, Chile and the Monterrey Housing Project in Mexico, both of which employ Elemental’s now trademark “half-finished-house” technique.

The approach provides residents with a half-finished, basic framework of a house that they can then modify and complete at their own pace according to their changing family situation and needs.

As soon as Mr Aravena was appointed curator last July for this year’s international architecture exhibition, he immediately set out to explain his vision to exhibitors.

“There are several battles that need to be won and several frontiers that need to be expanded in order to improve the quality of the built environment and consequently people’s quality of life,” he explained.

“This is what we would like people to come and see at the 15th International Architecture Exhibition: success stories worthy to be told and exemplary cases worth to be shared where architecture [have] and will make a difference in those battles and frontiers,” says Mr Aravena.

“When I saw the announcement of Aravena’s appointment and the theme, I thought that the Sha’abi housing was really the only option that we could work with,” says Prof Elsheshtawy, who sees several similarities between Sha’abi housing and Elemental’s approach to social housing.

“With all this in mind and given how relatively young the UAE is in terms of its urban and architectural development and the dominance of iconic projects, the Sha’abi housing immediately felt like it would be appropriate to the theme,” Prof Elseshtawy says.

“The Sha’abi houses are also an example of a social housing project and of an architecture that was very adaptable and which allowed residents to make changes. Each of the houses started out the same as a basic model, but over the years people have made changes. They added rooms, they modified the elevations, they added landscape features.”

Charting these changes will form a key part of the research that Prof Elsheshtawy and a team of UAEU students are conducting. It includes a detailed study of the remaining Sha’abi houses in the Al Ain suburbs of Sha’abiyat Al Maqam and Sha’abiyat Al Difaa.

“There are around 200 of the houses in these neighbourhoods, and we’ve documented the elevations of about 56 of those and we’ve drawn them next to each other,” the academic says.

“When you place them next to each other at the same scale you can immediately see the differences from one to the next, and it shows you the extent of variation and the individualisation of the different houses. No two houses are the same and that’s absolutely fascinating.”

For Prof Elseshtawy, the Sha’abi houses’ success and value rests, in part, in the lessons they can teach contemporary architects and designers about the need to provide people with cities and buildings that afford them a degree of licence and freedom.

“Sometimes architects have to stand back a little bit and let people modify their own space,” he says.

“Architects sometimes think that they can determine people’s behaviour through design, but that’s not always the case and in certain situations it’s very important to design environments that are open-ended, that allow activities to occur without architecture standing in the way.

“The result is a built environment that is much more receptive to people’s activities and needs and becomes more of an expression of people’s culture than some rigid framework that does not allow for change.”

One of the other key elements of the UAE pavilion will be an interactive map that allows visitors to see the location and distribution of the remaining Sha’abi houses across the Emirates and this will be accompanied by models of the houses, architectural plans and archive documents.

If the focus of this year’s UAE national pavilion is intentionally different, its architectural design will also mark a significant departure from the norm, Prof Elsheshtawy insists.

Traditionally, whether they have been at world expos or at biennales, UAE national pavilions have made some kind of literal or metaphorical reference to the UAE’s history or landscape.

The very first national pavilion, which represented Abu Dhabi at the Osaka World Expo in Japan in 1970 before the UAE’s founding, was a vague recreation of the Al Jahili Fort in Al Ain, whereas the most recent pavilions – at Shanghai in 2010 and last year in Milan – took their inspiration from the UAE’s dunes, wadis and irrigation channels.

It is a tendency that Prof Elsheshtawy is determined not to repeat.

“My main problem with these pavilions was that they were always representative of something,” he says.

“It was perfectly understandable that, in 1970 when the UAE as a nation was yet to be formed, that it would look at some historical precedent.

“But I feel these are now cliched elements and one of the things that I want to stress is that the pavilion should be a representation of how the UAE sees itself in the 21st century. It should be forward looking.”

nleech@thenational.ae