AL AIN // The head of UAE University's transport research centre is calling for all vehicles to be fitted with tracking chips, to catch them speeding or tailgating wherever they do it.

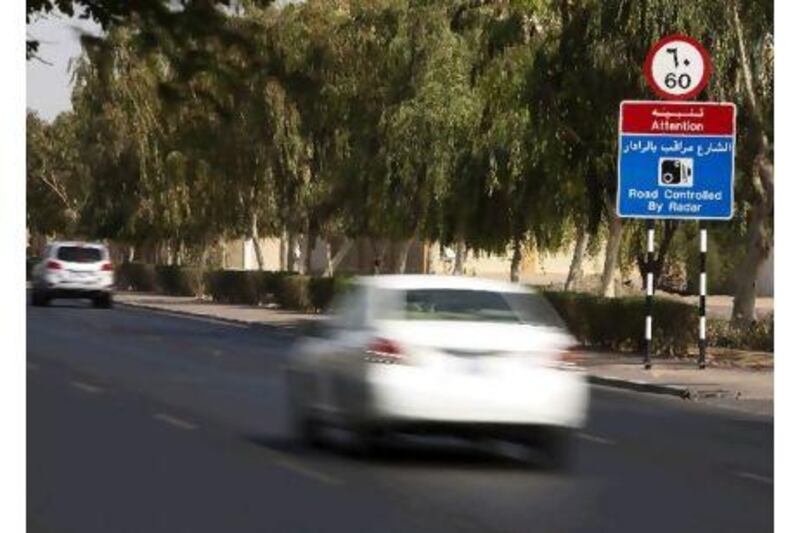

That way, speeding most of the time while slowing down only near speed radars would no longer be a way to circumvent speed limits.

The GPS-enabled tracking chips are already being tested in Japan, Singapore, Britain and the US. They would need a sophisticated communication network and monitoring centre, according to Yaser Hawas, the director of the research centre.

Drivers clocking above the speed limit would immediately receive a text message telling them they had been fined, he said.

Currently some traffic offenders receive texts when cameras catch them speeding, but the process is manual and inconsistent, he said.

The underlying point is that for the roads to be safer, drivers' attitudes must change.

And a consequence felt immediately is more effective than one felt days or week later.

"If I get a notification in the mail a month later, I do not recall the speeding or may not even care," Dr Hawas explained. "Getting something immediate might scare me and train me to become a better driver."

Dr Hawas recently conducted a study of the behaviours that contribute to aggressive driving and accidents. He interviewed psychologists, Department of Transport workers and more than 1,600 drivers who had recently committed traffic offences.

The research, commissioned by the Ministry of Interior, found that those caught for serious traffic offences often had excessive confidence in their driving abilities.

They were also disrespectful to other road users due to being tired or disoriented; angry about clogged roads or lack of parking spaces; influenced by other drivers; and encouraged to speed by the open road or favourable driving conditions.

The most effective way to correct drivers' attitudes is to make them accountable, Dr Hawas said.

He called for insurance companies to be given access to drivers' records, so they can penalise bad drivers with higher premiums.

The Department of Transport declined to comment on whether it would consider making changes to monitoring systems.

Another option would be speed-limiting devices - although Prof Brian Fildes, who has done vehicle crash and injury risk research in the UAE for the Accident Research Centre at Monash University in Australia, favours less intrusive means.

Australia's monitoring programme includes cameras mounted on randomly parked cars rather than at fixed locations that drivers are aware of, Prof Fildes said.

The programme reduced speeds by two to three kilometres an hour, he said. And in Victoria state, doubling the number of mobile cameras on the roads reduced accidents by about 20 per cent in one year.

"Getting people to change their behaviour is an enormous effort, but if you persist, ultimately, people will see the benefits and change," Prof Fildes said.

TransAD, which regulates Abu Dhabi's taxis, has an automated system in place that tells drivers who are above the speed limit to please slow down. If they do not, they receive a fine of up to Dh500. But fines might not work so well for other drivers who can more easily afford them. A better incentive, suggested Prof Fildes, was the threat of losing your licence.

"It helps to send them instant notification so that there is association between the event and the punishment, but those who speed and those who don't wear seat belts are anti-social in other ways as well," he said.

"We can't rehabilitate people or modify their personalities, but if they have something at stake then that is another issue."

Prof Abdulbari Bener, a public health researcher based in Qatar, has done extensive traffic studies in the UAE and said the problem mostly lies in a lack of accountability and of strict law enforcement.

"It does not matter what you do or what you install, because you could fix a radar to every traffic signal and they would be neglected," he said.

"For a wealthy country like the UAE, people have no problem paying the fine and asking a traffic department to forgive their mistakes.

"There should be no gaps or spaces in negotiating with a patrol department, but oftentimes there are."