Good news for air passengers tired of the slow-mo scrum of boarding the aircraft: researchers say they’ve found the optimal way of getting you seated.

We all hate the ritual of waiting to be called to the gate, queuing up and finally making it to our seat - only to find some shopaholic has filled the overhead locker.

Airlines find it even more irksome, as it can all lead to squabbles, missed “slots” and expensive delays.

For years, most airlines have stuck with the same system: first class first, then those with small children, and finally everyone else in blocks of seats.

Yet everyone knows it’s less than perfect. As people jostle for seats and lockers in the same area, they get in each others’ way, leading to queues in the aisles, stress and delay.

Studies suggest it’s actually the worst possible boarding method. Simply letting people grab any seat turns out to be better – though passengers hate it.

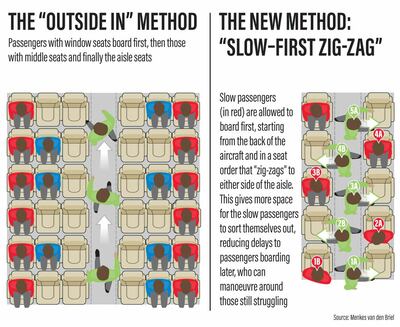

Now an international team of physicists claim to have found the best way to get us on board. The secret lies in giving the slower passengers priority and seating them in a specific pattern.

Led by Professor Sveinung Erland of the Western Norway University, the team found that it’s best to seat these passengers starting from the rear in order of seat numbers that zig-zag down the aisle (see diagram).

This creates more space around these passengers as they sort themselves out, reducing the risk of aisle jams that slows everyone else boarding after them.

Describing their findings in Ars Technica, a website covering science and technology, the researchers explain the technique with the analogy of packing stones and sand into a jar. If you get the stones in first, the sand can fill the gaps around them more easily.

Computer simulations suggest the slowest-first policy can cut boarding times by up to 28 per cent compared to giving priority to passengers who travel lighter.

That, at least is the theory, backed up by some very sophisticated mathematics. But will it work in practice?

The researchers admit there are some practical issues still to be resolved – not least stopping passengers “gaming” the system.

Airlines currently give priority to those who have paid for the privilege, or are slow because they either need assistance or have small children.

Yet if the new policy is to have a big impact, “slower” passengers will include those needing to stow lots of carry-on luggage. And among them will be the shopaholics who already cause so much resentment.

That, in turn, could prompt passengers to bring on as much carry-on luggage as they can, in a bid to be seated earlier – thus increasing delays.

As the saying goes, more research is clearly needed – and is underway. Gatwick Airport in the UK has just completed a two-month study of various boarding methods to find out which theory stands up best in real-life.

One front-runner is the “Outside-in” method, where passengers with window seats go on first, followed by those with middle and finally aisle seats.

That’s faster than the usual “seat block” approach, as people aren’t trying to stow baggage and sit in the same small area, or waiting while those already in aisle seats stand to let them in.

But while better than the block approach, this method has problems too – like people who booked neighbouring seats being unable to board together. That forces exceptions to be made – for instance, for families with young children – undermining the speed gain.

And then there’s the dirty little secret about boarding. Airlines are keen to get everyone seated quickly – but they don’t want it to be entirely hassle-free. That’s because they make a tidy profit out of priority seating schemes, which allow people to saunter onboard while smirking at those stuck behind the shopaholics.

Even so, the Gatwick trial is likely to identify small tweaks which could make a significant difference.

That’s often the outcome of such studies in Optimisation Theory, the branch of applied science which can help make life just a bit less irksome.

Every air passenger has benefited from its insights – right from the point at which they check in.

When things aren’t very busy, we may just pick a queue in front of any of the check-outs – only to find we’re stuck behind a couple with dodgy-looking suitcases and no passports. We then curse our luck, while watching the queue next to us whizz through.

At busy times, Optimisation Theory comes to our rescue – by deliberately robbing us of any choice. All the check-ins are served by a single line, which weaves this way and that across the concourse.

While often greeted with dismay, such “single-channel multi-server” queueing systems are mathematically proven to be far faster – and less frustrating - than allowing us to guess which check-in will serve us first.

Having a single feeder line ensures everyone ends up at whichever check-out has just beaten all its neighbours.

Airlines themselves rely on Optimisation Theory to solve a truly nightmarish problem: scheduling planes subject to passenger connections, crew transfers and rest periods and aircraft maintenance.

Using algorithms and ultra-fast computers, airlines calculate the optimal schedule that minimises downtime and maximises efficiency.

But fog-bound airports or faulty aircraft can demand that the whole optimised schedule to be recalculated - and with minimal delay.

Tellingly, Delta Air Lines has just revealed it’s working with IBM to use quantum computers – the ultimate number-crunchers – to “address challenges across the day of travel”. That’s code for optimising schedules when things suddenly go wrong.

But there’s one optimisation problem all women would like solved right now: eliminating the queues for the loos.

At first glance it seems easy enough. Studies show that women take around twice as long in the loos as men. So obviously women should get twice as many cubicles as men. Obvious, but wrong.

A mathematical quirk means it would take four times as many cubicles to give women the same queueing experience as men – which is prohibitively expensive.

There’s a solution though: let women use the same facilities as men.