BYLAKUPPE, India // Phurbu Tsering took to his knee to pick at a small patch of earthy, blackened soil. Four years ago, his five acres of farmland in India's south-west were so depleted by years of chemical fertilisers, he says, little grew and water would run off as if on concrete.

But now, the monsoon rains that will soon soak this region of rolling pastures and forests of sugar cane will disappear into the ground, sucked up by the roots of Mr Tsering's corn, wheat, papaya and lychee crops.

"You can see it in the soil; it's due to the organic [farming]," he said, grabbing a clump of the rich loam. Bags of homemade fertiliser stood ready for spreading amid rows of just-tilled corn. "When we fertilised with chemicals, we never even saw an earthworm."

Across much of India's agricultural heartland, this year's growing season has been superb. So good, in fact, that many farmers face the challenge of transporting their goods to market before they rot in the hot, humid air.

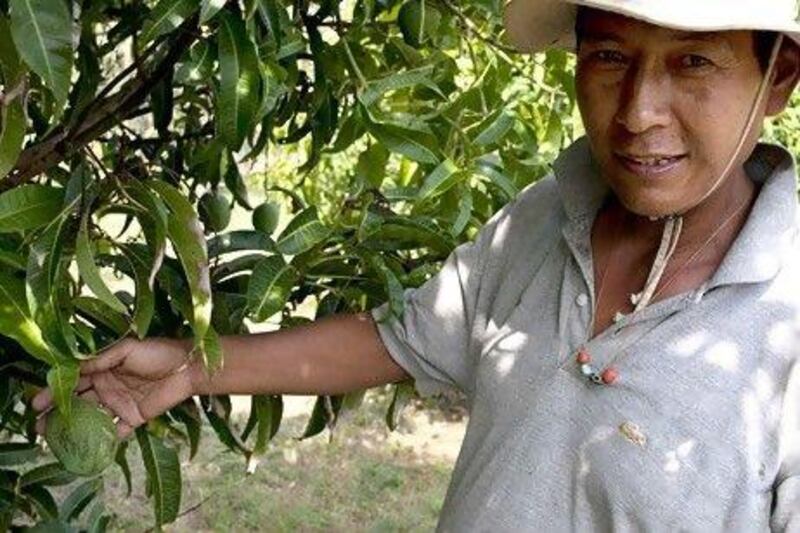

But Mr Tsering, 52, a Tibetan organic farmer in the Mysore district west of Bangalore, faces a different type of challenge. He is part of a small, struggling, organic movement that is aiming to convert a majority of the Tibetan refugee community's agricultural production into chemical-free farming, a change many believe could be key to long-term agricultural profitability.

Many of the 100,000 Tibetan refugees in India today are farmers. When the Indian government provided refuge to the Dalai Lama in 1959, it also began to establish a series of settlements to house the tens of thousands of Tibetans who fled Chinese rule along with their spiritual leader. These new arrivals found themselves with small plots of land to till and eke out a living.

Yet Tibetans are historically a nomadic people with little skill in row crop farming at low altitude.

International organisations, led by the Swiss, taught Tibetans how to grow maize using conventional, chemical-based farming practices. The plan made sense at the time: there was a ready market for corn as livestock feed, and the quick application of chemical fertilisers meant even the most inexperienced could make it to harvest.

Over the years, however, the Indian market for maize became flooded. Profits dwindled, labour costs soared and soil fertility diminished as more chemicals were needed to grow crops. It now takes five times the amount of bagged nitrogen and phosphorus to produce the same yield of corn, says Tenzin Damdul, who manages the Organic Research and Training Center in Bylakuppe, a programme funded by the Tibetan government in exile.

Tibetans have long been successful at marketing themselves politically. Now, farming experts in Tibetan refugee communities hope to build a similar following for their organic agricultural output. A new "Tibetan Organic" label has been created in the Mundgod settlement, north of Bylakuppe, and products such as processed chilli and medicinal herbs have already won organic certification in India, the United States and the European Union.

The trick, advocates say, will be establishing export networks and regional markets that will convince more farmers like Mr Tsering to reinvent themselves.

The move to organics has dual benefits. For Tibetan Buddhists, it is more sustainable to till the earth naturally, as their ancestors did for centuries under the snow-capped peaks in the high Himalayas. Dolma Yangchen, 59, a project officer in Bylakuppe, says ultimately organic farming is about helping her people return to a lifestyle they have long since left behind. "In Tibet, farming was purely organic. Organic farming is not only economic, but maybe it preserves what we had in Tibet."

But the shift is also about surviving in a competitive Indian farming industry.

"Farmers have to produce what the customer needs, what the market needs," Mr Tsering says, who notes that Indians are richer today, and consumers are willing to pay a premium for healthier, organic products. "We decided in 1960 to go for maize. We have to change that now. The whole thing, we have to change."

In 2008, Mr Tsering, along with 24 other neighbouring farmers in the Bylakuppe settlement, started in a pilot programme headed by refugee officials to make the switch from chemical-based growing. Each year since they have received 1,500 rupees (Dh100) per acre to help offset costs. It was just enough to make the change worth while.

But next year, that assistance in set to end, says Tseten Dolker, an agriculture extension officer with the Tibetan government. Agricultural specialists say it will be a challenge for others to follow in Mr Tsering's footsteps.

Today there are more than 27,000 acres of Indian farmland under Tibetan refugee control, and approximately 4,000 of those are certified organic. But high start-up costs have discouraged many others from making the organic switch. Organic growers in India must make their own fertiliser, usually from cow manure, which means more man hours than chemical applications. In the Kollegal refugee camp in the southern state of Karnataka, farmers once tilled 500 acres of organic corn, but that has dwindled to just 20 acres today, as soaring labour costs swallowed up profits. Farmers and agricultural specialists fear that once the annual subsidy vanishes, others will follow.

"We have to see the option for other crops, like grapes, fruit and even wine," said Mr Tsering as he strolled through his property under the midday sun. Like savvy organic growers in the West and Europe, he has sought to diversify. Soon, he will be erecting a long greenhouse to help him extend his growing season.

Mr Damdul, of the organic research centre, says these initiatives are precisely what organic farming in Tibetan communities in India, and elsewhere, demands. "At our settlement … we are growing only through rainfall during the monsoon. But if we were able to supply for a whole year, people would pay more."

For now, though, these are purely aspirational goals. On Mr Tsering's five acres, it is still maize sold for cattle feed that makes up the bulk of his organic output. "There's some benefit for people, and for the land," Mr Tsering says. "But there's no benefit for my pocket. For now, the animals are eating better than us."