Samir Farag wants to reclaim the glories of ancient Luxor, even if it means demolishing a village or two. Will the governor's dreams of tourism dollars save the city or destroy it? Simon Mars reports.

It's the first week of December and a woman, her four-month old baby in her arms, is sitting outside her home in Gourna, a village high up in the hills of Luxor's West Bank. She's waiting for her final eviction notice. She expects it any day now. If all goes according to the official plan, she and the other remaining villagers will be gone in a few days, and their houses will be leveled. The woman's child will almost surely be the last to have been born in Gourna, a village built on a network of ancient Egyptian tombs.

On another recent day in Luxor, I am sitting in a garden looking up at the New Winter Palace hotel - one of Luxor's tallest and, it's generally agreed, ugliest buildings. As the sun sets, I watch a lone labourer, perched on a narrow ledge on the hotel's roof, chipping away at the building with a sledgehammer. The garden where I'm sitting is attached to the Old Winter Palace hotel, a grandly appointed 19th-century structure built in the British colonial style. While the shabby modernist New Winter Palace is being demolished, the antique charms of its hundred-year-old sibling are being enhanced with a five-star upgrade.

Out with the new and in with the old: this is Luxor in a nutshell. With plans to turn the city into one of the world's largest open air museums, the Egyptian government has busily set about demolishing eyesores such as the New Winter Palace and obstructions such as the hardscrabble village of Gourna. Meanwhile, they are preserving everything that is fine and ancient- all so that tourists can commingle with a carefully curated version of Luxor's past.

The Egyptian tourist board says that Luxor, a city of 350,000, situated some 700 kilometres south of Cairo, boasts a third of the world's ancient monuments. After spending a few days there, you begin to believe it. On the Nile's West Bank in Luxor, there are the tombs in the Valley of the Kings and Queens (including Tutankhamen's, which is like a box cupboard compared to others that stretch on into the mountains in chamber after chamber); the temples of Madinat Habu and Hatshepsut and the colossal remains of the Ramesseum (the statue that inspired Shelley's Ozymandias, still lying there broken on the ground). On the East Bank, in Luxor proper, there's a main cluster of hotels, restaurants and shops as well as the magnificent and extraordinarily well-preserved temples of Luxor and Karnack.

Luxor is a city that lives off the past. Its monuments, tombs and temples draw over two and a half million visitors each year. And tourism will be even more vital to the city's - and Egypt's - future. More than 12 per cent of the country's workforce currently works in tourism. With Egypt facing the need to generate at least six hundred thousand jobs each year just to keep pace with new entrants into the country's labour market, expanding the tourist industry is an official priority. The country may lack the oil money that's building the Gulf's new cities, islands and landmarks, but it does possess a resource the Gulf lacks: the remnants of one of the world's most astounding civilizations. And so Egypt has begun making a concerted effort to use its past to build its future.

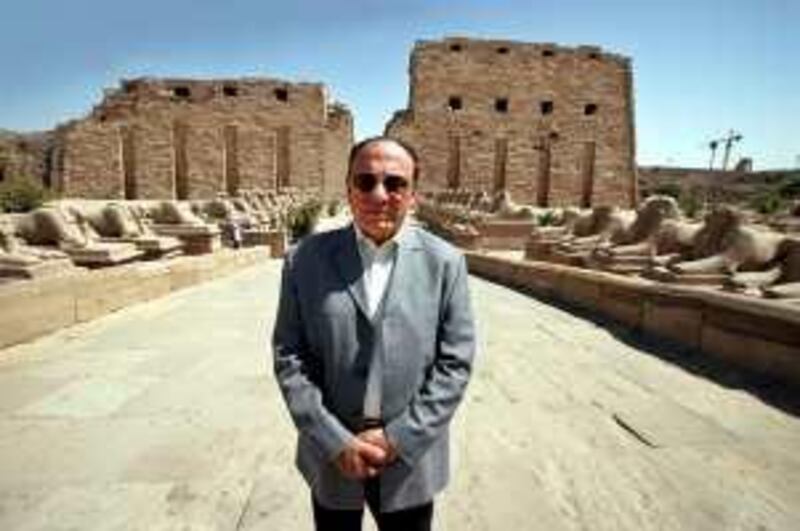

In July 2004 Samir Farag was appointed governor of Luxor by President Hosni Mubarak with a mission to renovate Luxor's antique sites and redevelop the city as a world-class tourist destination. The task entailed removing all the signs of human habitation that had, over the years, built up on and around the city's historic sites. As soon as Farag took office, in other words, Gourna's days were numbered.

Over the past two centuries, the village of Gourna cropped up bit by bit over the tombs of thousands of lesser nobles halfway between the Valleys of the Kings and Queens. The dead supported the living there for decades, with the tombs providing the four thousand villagers an income either as tour guides or via the sale and manufacture of souvenirs. Always a ramshackable development, the village provoked frequent complaints over the years - that its inhabitants were robbing the tombs or that their very presence spoiled an important archaeological site. Various plans to move the villagers off the site were broached. But none, including a celebrated attempt by the Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy to move them into a specially built new city, ever came to fruition - in part because the villagers refused to leave.

And then Farag arrived. Sitting in his dark, wood-lined, office, the governor speaks passionately about his mission. Complaining that Luxor has long been neglected by developers in favour of holiday resorts such as Sharm el Sheikh, he runs me through a powerpoint presentation of his plans for the city. Hundreds of photographs are projected onto the wall: of old slums and housing; of brightly coloured tomb-wall paintings in the cellars of houses in Gourna; of new homes and widened streets, along with artists' renderings of Luxor's sleek future.

That future is still a long way off. Farag's first task was to modernise the city's infrastructure: electricity, sewage, water, phone lines and roads. "The only real road we had was the Corniche," he says. "But I didn't start with the Corniche, because every other governor used to come here and begin working on the Corniche. I knew if I started there I would lose the support of people." But a loss of public support was inevitable when Farag proceeded with the rest of his plans. He clicks again on his laptop and brings up a five year-old picture of Gourna: "It was a slum area," he says. "The people lived on top of the tombs in their houses. They didn't have water, electricity, nothing. It was a very miserable life."

That's not a description many of Gourna's inhabitants would accept. Many say that Gourna has been their families' home for more than a century. They were born there; their parents and grandparents died there. But most importantly, they made their living there. To persuade them to relocate, the governor built New Gourna, a freshly constructed, planned settlement with schools, a hospital, police station and a cultural centre, five kilometres from their old location outside of town. "Of course, nobody wanted to move," he admits, "but we started with the young generation. I went to them and told them they could have a better life; 'you can have electricity, sewage, clean water, TVs, everything.'"

The new settlement, he says, cost $20 million (Dh73m) to build, and Old Gourna's inhabitants were given their new houses outright. Some extended families in the village have been given multiple, adjoining homes, Farag says, and the entire settlement's construction reflects their preference for single-storey houses. The governor also insists that no undue pressure has been exerted on villagers to get them to relocate.

But that's another thing the remaining inhabitants of Old Gourna dispute. When I visit the half-demolished village, the electricity has already been cut off for a week. It may be true no one has been forcibly evicted, one old man tells me, but it all depends on how you define "forced". One villager shows me the small workshop in his home, where a couple of workers are still sawing limestone for the bas-reliefs and small statues they sell to tourists. The villager clings to Old Gourna. When he moves, he says, he will lose his shop and his livelihood. "You kill my future," he says, "you kill my life."

Another man, my guide through Old Gourna, once owned a small shop in the village. But he has already relocated. He wants me to see what New Gourna looks like, so drives me there on the back of his motorbike. At first glance New Gourna looks similar to some of Dubai's housing developments - a collection of newly painted box houses lining clean tree-lined and flower-lined streets. My guide - a smiling, spry and well-preserved 60-year old - lives with nine members of his extended family in two houses separated by a courtyard that contains pigeons, chickens and a sheep for Eid. Inside, he's painted the walls a beautiful Moroccan blue. "Yes, it's clean here," he says. "You have water. Everything is OK."

But there's no work in New Gourna. No tourists visit; in fact most tourists don't even know the new village exists. Back in Old Gourna my guide had his shop, one that had been in the family for decades. He opens a box to show me some artifacts and statues carved by his grandfather - carefully preserved and wrapped in biscuit tins, waiting for the day when the government gives him the new shop they've promised him. It's been over a year; he keeps asking and they keep giving him the same answer: "be patient." So he keeps his life in biscuit tins and he waits.

As the governor's reclamation plans continue, a fate similar to that of Old Gourna's villagers now awaits some 5,000 or so people on the East Bank of the Nile. This time Farag is opening up the Avenue of the Sphinxes, a three-kilometre pathway, once lined with thousands of Sphinxes, that links the Karnack and Luxor temples, which was used each year as a processional route during the festival of Opet to celebrate the seasonal flooding of the Nile. Again, the Governor says, all the people moved will be compensated. "The owner of the house will get the price of his land and the price of the house," he says. "People who are renting will be offered either a new home or money." (Property owners will get a huge windfall, he says, given that rent caps have prevented them from earning much in the past.)

And all this comes in addition to one of Farag's earliest beatification projects: demolishing the shacks, shops, houses and football pitch that once occupied the piazza in front of the temple of Karnack. Go there now and you see a vast open area that permits, for the first time in hundreds of years, a view of the Nile and the temple of Hatshepsut high up on the Theban Hills. Farag's energy and excitement are impressive, but it's hard to reconcile his zeal for the clean sweep with the messy realities of Luxor. He insists his plans are meant to ensure the city's future - that the pain some of its residents are now enduring will be worth it in the end, both for them and for their children.

And the Governor also wants to make clear he should not be regarded simply as a one man demolition crew; he's also been building. There are now highways linking Luxor to the Red Sea resorts of Hurghada and Marsa Alam, so that people on holiday there can make day trips to the city. Six thousand tourists make that journey every day now, all of them bringing money to spend in Luxor. The city has an airport terminal that can now accommodate up to seven million passengers a year; a new railway station and souk; a hospital; a cultural centre providing work and training for the city's 30,000-strong Nubian community; a women's centre; a large wireless internet zone; a library and a heritage centre. An Imax cinema is also on the way.

Overall the governor says the city has spent 1.2 billion Egyptian pounds (Dh808m) on infrastructure since he's arrived - changes that have already had an impact on the city's economy as a whole. "We used to close most of our hotels after Christmas and New Year but now have full occupancy most of the year," he says. "Starting from this October, we don't have a single hotel room - not one." But still the opposition persists: earlier this year a demonstration of 3,000 people outside Karnack almost turned into a riot. A court case protesting the Gourna evictions is pending - marking the last hope of Old Gourna's few remaining few residents.

But that only means it's time for the next stage of the plan, Farag believes. Just around the corner is a development sure to create new livelihoods for the inhabitants of places like Gourna. The governor says he's building new resorts capable of holding tens of thousand of people outside the city; that Luxor will soon have the biggest youth hostel in the Middle East; that a forest of jatropha trees, whose seeds contain up to 40 per cent oil, is being grown to provide the city with engine oil; that treated wastewater is being used to irrigate 22,000 acres of farmland; that investment zones are being opened to bring in new businesses. "We are building a new factory just to produce a lot of things for the hotels," he says. Farag thinks the city can double the annual number of tourists it currently hosts. In the end, he says, people will appreciate what he's done.

Meanwhile, my guide sits in New Gourna with his family. His children seem willing to give the governor the benefit of the doubt. They're hoping that Farag means what he says - and that he has the power to make it happen. But for now my guide waits, hoping for the chance to bring his grandfather's statuettes out of their tins and set up shop again.

Simon Mars is a TV producer based in Dubai and Cairo.