Sudden, radical and often violent, revolutions are usually hard to miss. But it is entirely possible to live through a scientific revolution without noticing until we look back to see just how different our lives have become.

Such a revolution is now sweeping through medicine.

In the quest for cures for everything from cancer and heart disease to organ failure and lost limbs, scientists are increasingly turning towards the same source of answers: the human body itself.

After decades of trying but failing to match our own self-healing abilities, researchers are trying to understand how they work and how to boost them.

Pharmaceutical giants Glaxo- SmithKline and Amgen recently joined leading academic researchers to find ways of using our immune systems to seek and destroy cancer cells.

Known as the Cancer MoonShot 2020 programme, it builds on recent advances in such “immunotherapy”, which have had success in treating patients with lung, skin and blood cancers.

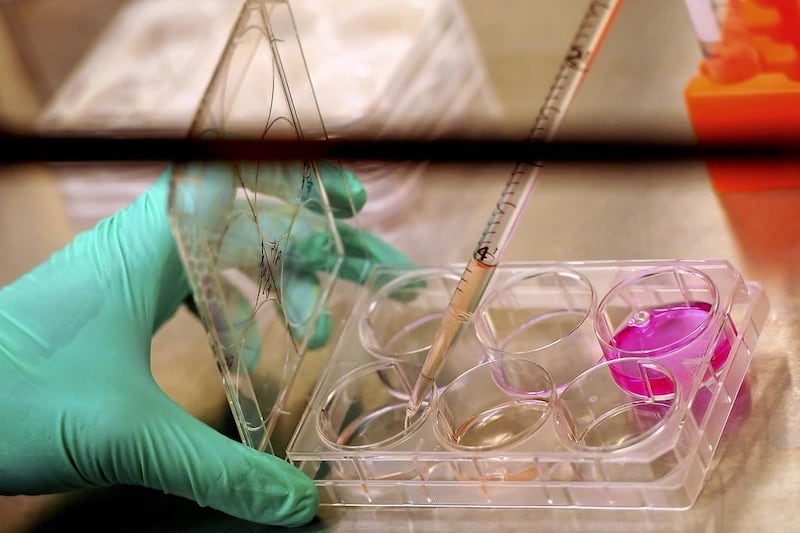

Meanwhile, biomedical researchers worldwide are learning to use stem cells – part of the body’s own “repair kit” – to create body parts and even entire organs to order.

Collections of kidney, lung and heart cells have already been made in the laboratory. Work is under way to scale them up, creating replacement organs from patients’ own cells, which can therefore be implanted without fear of rejection by their immune system.

But the biggest advances look set to emerge from one of the most astounding facts about the human body: that most of it is not human at all.

At least half of the cells in our bodies are microbes: bacteria, viruses and other organisms we have acquired in our lifetime.

Collectively known as the microbiome, these fellow travellers might seem like the enemy within. Yet it is now clear that they are vital to our health and well-being – and may explain otherwise perplexing links between diet and the onset of lethal diseases.

We start acquiring our microbiome from the moment of birth, picking up microbes from our mother and anyone else who touches us. Our cells then use specific genes to encourage the growth of beneficial bacteria while attacking harmful ones.

Breastfeeding provides another rich source of microbes, as well as complex carbohydrates and proteins that are specifically designed to encourage the growth of Bifidobacteria, a type of gut bacterium that wards off pathogens.

By adulthood, the microbiome has developed into a complex of hundreds of different types of bacteria, plus at least as many varieties of viruses and fungi.

The biggest concentrations – about 100 billion per millilitre – are found in the gut, where they work alongside human cells to digest nutrients.

Now scientists are investigating this collaboration and how it affects our health for good or ill.

This month, a team in the United States published research into how the interaction of human and microbial cells is affected by what we eat, thus casting light on the link between diet and disease.

According to the team – led by Athena Aktipis, an assistant professor at Arizona State University – in healthy people the two types of cells benefit from each other, with the microbes producing energy and vitamins and attacking pathogens, while the human cells provide them with conditions that allow them to thrive.

But according to Prof Aktipis and her colleagues, this symbiosis can be disrupted by a diet that is low in fibre but high in sugar.

Unlike dietary fibre, sugar can be used not only by human cells but also by potentially harmful microbes, such as pathogenic E. coli. The resulting outbreak of “cell wars” can then lead to obesity, diabetes and an early death.

In separate research published this month in the journal Nature, a team – led by Rachel Perry, a postdoctoral fellow in endocrinology at Yale University – described another potential link between the microbiome and obesity. Experiments on mice showed that changes in gut microbes can alter hormones linked to hunger and digestion – leading to over-eating and obesity.

Diet-related cell wars are also suspected of being triggers for two of the biggest killers in developed nations: cancer and heart disease.

The link with cancer is thought to come about via the immune system’s attempts to fight the pathogens as they attack internal organs. The result is inflammation, leading to malfunctioning healthy cells, which then grow uncontrollably – the hallmark of cancer.

In the case of heart disease, one culprit is thought be the ability of “bad” microbes to turn nutrients into compounds that create artery-clogging plaques.

Recent studies of healthy volunteers on vegan diets found their microbiomes appear to lack these organisms, reducing the risk of heart disease.

Evidence is also emerging that the microbiome provides the “missing link” between the Mediterranean diet – rich in fresh fruit, vegetables and olive oil – and better long-term health.

The microbiome also seems to explain otherwise baffling links found by researchers between heart disease and dental hygiene.

Our mouths play host to more than 100 species of microbes, and gum disease and tooth loss is a symptom of the kind of cell wars now linked to serious disease in the rest of the body.

The promise of more such insights has prompted a proposed US$121 million (Dh444.5m) National Microbiome Initiative among US government departments including the National Institutes of Health.

Unveiled last month, one of its key aims is to set up long-term human studies to reveal more about the links between health and the microbiome.

Meanwhile, drug companies are racing to find compounds that can target specific microbes and quell a cell war before it triggers disease.

Whether so-called probiotic supplements with “good” microbes make any difference remains to be seen. One major question facing researchers is the extent to which all of us need our own special mix of microbes to be in peak condition.

But there is one insight of the microbiome revolution that looks set to stand the test of time: when we eat, we are feeding ourselves and our non-human “other half”.

Robert Matthews is a visiting professor of science at Aston University, Birmingham.