Mention crystals and we think of hard substances – perhaps jewellery or clumps of rock – that may be attractive and brightly coloured.

We certainly do not think of substances that can bend like plastic and even heal themselves when damaged. Yet a research group in Abu Dhabi has been working with crystals with these very properties.

The bendable crystals are described in a scientific paper as having “exceptional mechanical flexibility”.

Crystals have an ordered internal structure and it is normally substances with a disordered internal structure, such as polymers, that are able to bend.

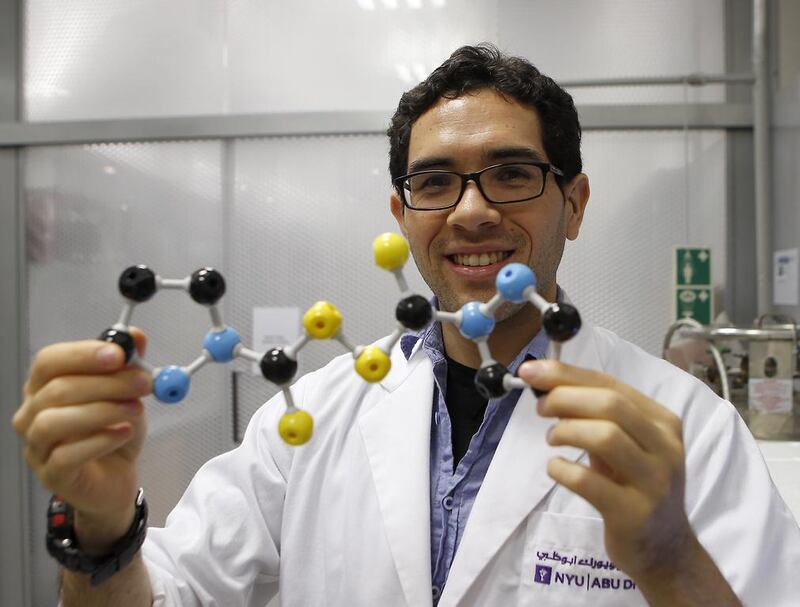

“Crystals are usually perceived as brittle entities,” says the scientist who led the research, Dr Pance Naumov, an associate professor of chemistry at New York University Abu Dhabi.

The research centres on a crystalline substance called hexachlorobenzene, which consists of a hexagonal ring of carbon atoms, to each of which a chlorine atom is attached.

When pressure is applied to particular faces of the crystal using forceps, the crystal can bend up to 360 degrees, and it retains this bent shape after the external pressure is removed.

The way in which the crystals behave as they become deformed was revealed by analysis with a scanning electron microscope, infrared spectroscopy, X-rays and other methods able to uncover the internal structure. Some of this work was undertaken by collaborators at the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute in Sayo.

“We tried to analyse the crystal before and after bending to understand the changes that occurred during the process,” says Dr Naumov.

The crystals show their remarkable bending property because layers within them separate and slide over one another. Bonds break between the layers when pressure is applied, only for new bonds to form between the layers.

Dr Naumov and his co-researchers published their findings as Spatially Resolved Analysis of Short-range Structure Perturbations in a Plastically Bent Molecular Crystal in the journal Nature Chemistry. The senior authors of the work were Dr Manas Panda, who was based at NYU Abu Dhabi at the time, and Dr Soumyajit Ghosh, of the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Kolkata, India.

Potential applications of bendable crystals include their use as actuators, components that control systems of various kinds. Although Dr Naumov’s group will “leave the applications to engineering”, the researchers will be continuing to work with flexible crystals to understand them better from the perspective of fundamental science.

Dr Naumov is engaged with other work related to crystals with surprising properties. A recent line of research centres on self-healing crystals, part of a wider project on “smart materials”.

“The main idea behind this project was to create materials that had the property to self-heal: when they’re broken and put together, over the course of time they will come together spontaneously and they will mend the defect,” he says.

While the field of self-healing materials is “quite mature”, Dr Naumov says most work had been on polymers or liquid crystals.

The first report of a self-healing polymer dates from 2001 and interest in them remains high. Self-healing polymers range from those that have capsules of glue-like material embedded in them to others with tiny vessels that, when ruptured, automatically deliver material to an area of damage. Yet more types return to their original shape if heated. These technologies have led to the development of self-healing paints and coatings and there have been predictions that we might eventually even see self-healing cars or buildings.

In contrast to a self-healing polymer, a self-healing solid crystal – a crystal is defined as having a form that is geometrically regular and with faces symmetrically arranged – is out of the ordinary.

“We would not normally expect such materials would self-heal because the molecules are not diffuse,” says Dr Naumov.

The researchers considered chemical reactions that could happen reversibly and used this to narrow down the crystals they considered testing.

Tests were carried out on crystals of a substance called dipyrazolethiuram disulfide, which was thought to have good potential for self-healing without the input of energy, such as heat.

“The crystal structure has several sulphur-sulphur close contacts and we thought this would allow the molecules to reorganise and, thus, heal,” says Dr Patrick Commins, a postdoctoral associate in Dr Naumov’s laboratory who carried out much of the work.

The crystals were cracked with a scalpel and the two pieces moved apart from one another. They were then compressed together again and left for 24 hours. The crystal was then inverted and gently prodded and, in some cases, the two pieces did not separate. Dr Commins says he was “astonished” when he discovered that the crystals could heal themselves.

“The work has a lot of potential towards creating new materials. Everyone can imagine how incredible it would be to have common items self-heal. However, this is still a burgeoning field and it will take time to fully understand and apply this newly discovered property,” he says.

By measuring the tensile strength of the crystals, the scientists were able to calculate that they had achieved about 7 per cent healing.

“It’s very low self-healing but it’s important because it’s the first report of this effect. It’s … [a] proof-of-concept study,” says Dr Commins.

The group is now carrying out further studies to better understand the scope of self-healing in crystals, with Dr Commins suggesting it is likely to be found “across many crystals and it’s just waiting to be discovered”. What applications these crystals might have remains, however, hard to predict.

“It’s too early to speculate. As of now, the material that I made heals slower, and to a much lower degree, than self-healing polymers. And this is partially because it’s the first one that’s ever been made. It’s like comparing the first electric car to a [Chevrolet] Corvette,” he says.

Until it is better understood, the current technology for self-healing crystals will, said Dr Commins, lag behind the standard for other self-healing materials. But this latest research nonetheless opens up a world of possibilities set to be realised in the years to come.

newsdesk@thenational.ae