The lush green countryside surroundings were unfamiliar, as were the uniforms.

Woodland camouflage had replaced the desert fatigues they wore during the liberation of Kuwait in 1990-91. This was the Emirati troops’ first posting to Europe.

But the mission was clear – ensure the fragile peace that had been brought to Kosovo after a year of fighting there.

The UAE joined Nato’s Kfor peacekeepers in 1999 and undertook an aid mission that involved feeding thousands of fleeing refugees on the Albanian border.

Serbian forces launched a brutal crackdown on the population of Kosovo in 1998, after sporadic fighting between the Kosovo Liberation Army and Serbian special police.

The people of Kosovo, ethnic Albanians and mostly Muslim, had long been at a disadvantage and persecuted by Slobodan Milosevic’s regime in Belgrade.

Hundreds of thousands would flee the fighting and the ethnic cleansing of villages, where men and boys were shot dead by Serb forces, although there were abuses on both sides.

Watching TV broadcasts of the aftermath of atrocities 5,000 kilometres away, the UAE's Founding Father, Sheikh Zayed, decided that his country had to help.

Few if any of the Emirati soldiers had witnessed such scenes first hand before.

Maj Gen Obaid Al Ketbi remembers patrolling deserted villages outside Pristina, Kosovo’s capital.

“There was no one walking in the streets,” Gen Al Ketbi says in his Abu Dhabi home, 20 years on.

“We waited a while and we saw a man come out into the street shouting, ‘Thank God, help has arrived’. Almost immediately, people began coming out of their houses.

“The mosque was destroyed and the imam had been taken and shot in the head, in front of his family.

"The people told us that the imam had always dreamt that his son, who was deaf and mute, could receive medical treatment.

“I picked up the phone and called Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed. He said that the family were to be immediately brought to the UAE.”

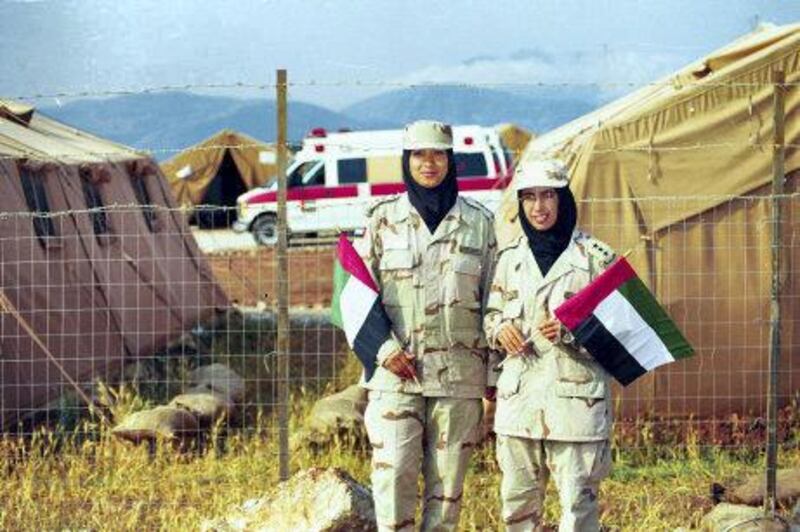

Almost 1,500 Emirati troops would serve in Kosovo over two operations.

One was with the Nato-led Kfor peacekeeping force from the spring of 1999 to late 2001.

About 1,200 troops were spread across six camps with Nato’s Multinational Brigade North in Vucitrn, where more than 100 Kosovars were massacred in May 1999.

The other operation was the White Hands aid mission across the border near Kukes, Albania, between March and late June 1999.

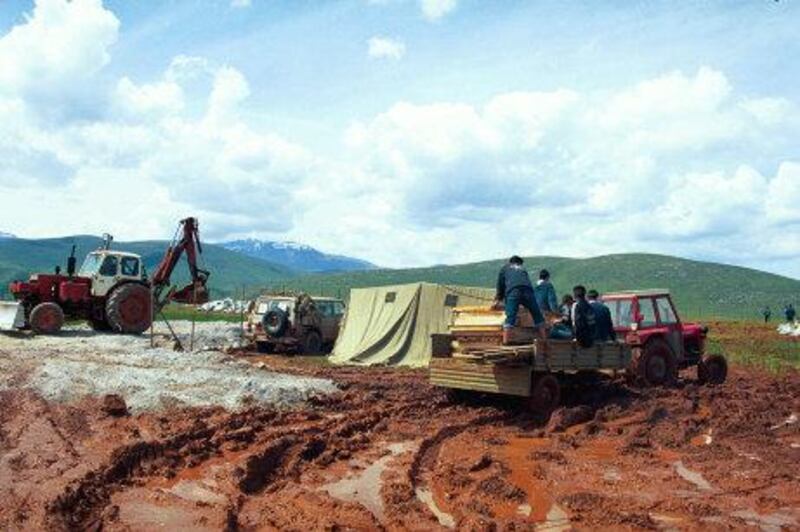

The first hurdle for the initial troops sent in to set up the White Hands aid camp was getting to the planned site, a patch of low-lying land nestled between mountains near the Albania-Kosovo border.

“Nato forces were reluctant to let us fly in, saying it was risky to allow pilots to land because of the mountains,” says Gen Al Ketbi, who began his career in the UAE Air Force and trained at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas, among other places.

His pilots scanned the area and found a 50-year-old abandoned airstrip.

They slammed the first C-130 Hercules down safely on to a makeshift runway, then brought in equipment to build a refugee camp.

“It was not easy to reach but thanks to God, and with good co-ordination, we succeeded. It was an amazing effort,” Gen Al Ketbi says.

Aid, goods, doctors and air-traffic controllers were brought in to manage the operation, at times hampered by bad weather.

“The type of terrain – it was all muddy land – and weather conditions were difficult. One moment it was snowing and sunny the next,” he says.

“Yet we built a camp in co-operation with Red Crescent in the shortest time possible. It was a unique mission.”

As refugees streamed across the border, the Emiratis had to expand a camp that was originally built to house 3,000 civilians, and have their kitchens working around the clock.

“Suddenly, demand was so high we had to expand to 10,000 refuges and house an additional 5,000 around the camp,” Gen Al Ketbi says. “So we had to service 15,000 people every day.”

A regular day at the camp for the soldiers meant waking up at 5am. Breakfast was served about 7am.

“Breakfast was hot meals like those that you would have at home. We had our cooks," he says. "After breakfast, the children would go to school at the camp.

"We opened schools where we brought people from Kosovo to teach. The camp was open. We had journalists living with us."

Up to 45,000 hot meals were served every day. It was known among other militaries as the “five-star camp”.

“We felt proud hearing that and Emiratis today should feel the same," Gen Al Ketbi says.

“We are lucky to have a leadership who invested in us to help others. We were not only servicing the refugees but all the people of Albania.

"This was a humanitarian assistance, part of the UAE’s strategy to help wherever help is needed.”

Gen Al Ketbi’s home in Abu Dhabi is covered in pictures and mementos of the Balkan operation.

In many, Emirati troops trudge through mud, treat civilians for injuries and feed long queues of refugees.

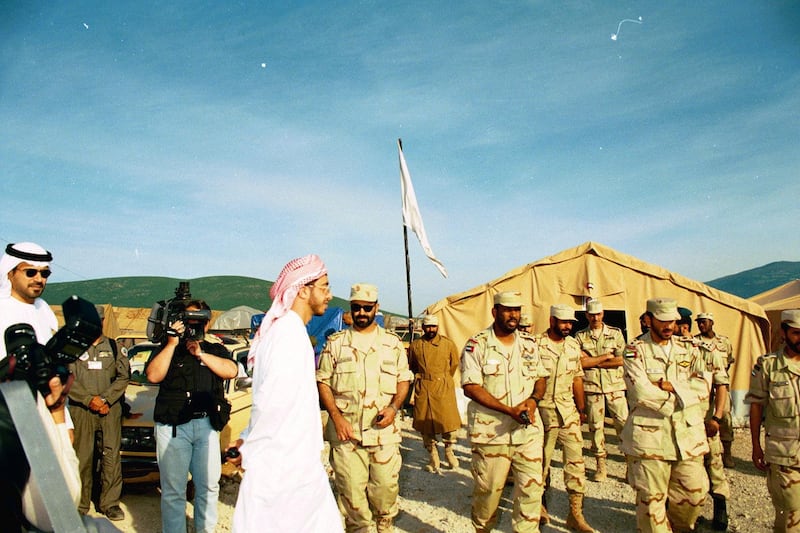

Over three months the camp received visits from UN dignitaries including secretary general Kofi Annan, and Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed, then Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces, who would become Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces in 2004.

Sheikh Mohamed earlier visited Emirati troops as they trained in France for the Kfor mission.

“It was our most important visit,” Gen Al Ketbi says. “He lifted the morale of the entire camp and instructed that we expand to accommodate as many people as required.

"If there was one lesson that we all learnt from Kosovo, it is that preparation is crucial.”

Nato’s intervention and the bombing of Serb forces and cities led to the withdrawal of Milosevic's forces. Eventually refugees were able to return to their homes.

“When the announcement was made that the refugees could return, we lost control for a few minutes because everyone was overwhelmed with happiness,” Gen Al Ketbi says.

“We had to hold them back and explain that the way back could be dangerous because of mines and we had to do it carefully.

“You could see tears in their eyes. They had formed a bond with our soldiers so it was hard to leave for everyone.”

He was the last to leave the White Hands camp in the summer of 1999, three months after the start of the mission.

Today he still reflects on what civilians were exposed to, and how he and his troops were affected.

“The hardest part was when you first receive refugees and particularly women,” Gen Al Ketbi says. “The women would be so scared of seeing any men because many were victims of rape.”

Over time, he says, they gained their trust. The first baby born in the camp was named Fatima after Sheikha Fatima, wife of Sheikh Zayed.

“They became our children. We became a family,” he says. “We were happy for them but it was hard to see them go.”

Between April and June 1999, about 19,000 refugees received treatment at the camp’s 200-bed hospital and mobile clinics.

Col Yousef Al Harmoudi, now retired, was in charge of the medical operation, overseeing 22 doctors and 30 nurses, some of whom were refugees.

“This wasn’t my first mission but it was the first in the heart of Europe,” says Col Al Harmoudi, whose team had just days to set up the facility amid snow and mud.

“We would see four seasons in a day, from cold to hot to warm weather.

“We met with the Albanian government and they agreed that we open a field hospital.

"The first team that left the UAE was on April 15 and by the 17th the entire team was there.

"On the 20th we opened and began accepting patients, most of whom came from surrounding camps."

He says hot meals, infrastructure, sanitation and hot running water drew in thousands within days.

“At other camps that belonged to Italian, Greek, Scottish forces, the refugees received three frozen meals distributed in plastic bags once a day.

“Our kitchen worked 24 hours a day. We used to give three hot meals and snacks in between.”

“Everyone was registered and had an ID badge.”

Some refugees were hired to help run the camp, being paid up to $200 (Dh740) a week, while others voluntarily helped with translation and registration at the hospital.

As summer arrived in southern Europe, the baking heat brought many casualties to the clinic.

“We saw a lot of illness, the majority of cases being dehydration in the elderly, women and children because they had walked long distances,” Col Al Harmoudi says.

“There were also chronic illnesses such as diabetes and high cholesterol.”

Many needed therapy to talk about the atrocities. Some of their stories he finds difficult to forget.

“There was an old woman who had lived in a mansion [before the war]," Col Al Harmoudi says.

“She was screaming in agony and slapping her face because they had slaughtered her son in front her eyes and raped her daughter and taken all her belongings."

Every day, the team would hold a conference to update journalists and UN officials.

“One journalist asked us why we had come. ‘Is it because you are Muslims’? she asked.

“We said it wasn’t because we were Muslims but for humanity,” Col Al Harmoudi says. “We showed her how our first patient was a Serb who was tortured by the Serbian forces.

“We are the children of Zayed and this is his legacy that he left for us – to love everyone and support everyone and anyone in need.”

During their time at the camp, he says, some refugees were married at a small mosque by an imam.

Other facilities were set up to bring a semblance of normal life to its occupants.

“We had basketball, football and playing fields to entertain the refugees and a cinema that screened Arabic films, dubbed in Albanian," Col Al Harmoudi says.

“We wanted to keep them entertained and forget the atrocities they had witnessed. We opened a school to ensure that the children’s education was not interrupted.”

Young soldiers who were rotated into the camp from the UAE were eager to serve, he says.

“It wasn’t just a job for them. They were looking forward to serving the UAE abroad.”

A war zone is not without its crooks, as Col Al Harmoudi discovered.

“The UAE had rented the land where the camp was based and almost every day we would find someone coming to us, claiming that they were the landowner and demanding we pay them rent,” he says with a laugh.

“One day four different people came to us and another day six different people. It felt like we were paying rent every day.”

The UAE, then with a much smaller international profile than it has today, gained much attention for volunteering to serve in Kosovo.

One Nato-employed journalist, Capt Monika Bliks, wrote of "exotic, Arab music" travelling through the camp and of how every month about a dozen children with special needs were flown to hospitals in the UAE and Europe for specialist treatment.

Capt Bliks also wrote of flights carrying $15 million worth of food, school supplies and medical equipment arriving, paid for by the “warm-hearted UAE”.

Col Al Harmoudi says the decision to take on the mission was an important one.

“The legacy Sheikh Zayed left for us is one of tolerance, serving humanity, peace, accepting others," he says.

"It will remain in our heart and the hearts of our great-great grandchildren and generations to come.”

![“We would see four seasons [in a day], from cold to hot to warm weather," says Col Yousef Al Harmoudi. Courtesy: Maj Gen Obaid Al Ketbi](https://thenational-the-national-prod.cdn.arcpublishing.com/resizer/v2/76FNDBJYQABBWIQJWBA5KNWN5Q.jpg?smart=true&auth=3c5136b23a4573955969faf3dc5a0990be486ccdfb666ffc3c7da79fb5b16ab0&width=800&height=539)