Sheikha Hoor bint Sultan Al Qasimi has a passion for the past that has been realised in a collection of buildings that promises to become as prestigious and eyecatching as the artists and exhibitions they are likely to host.

In architectural terms, at least, the future certainly isn’t what it used to be.

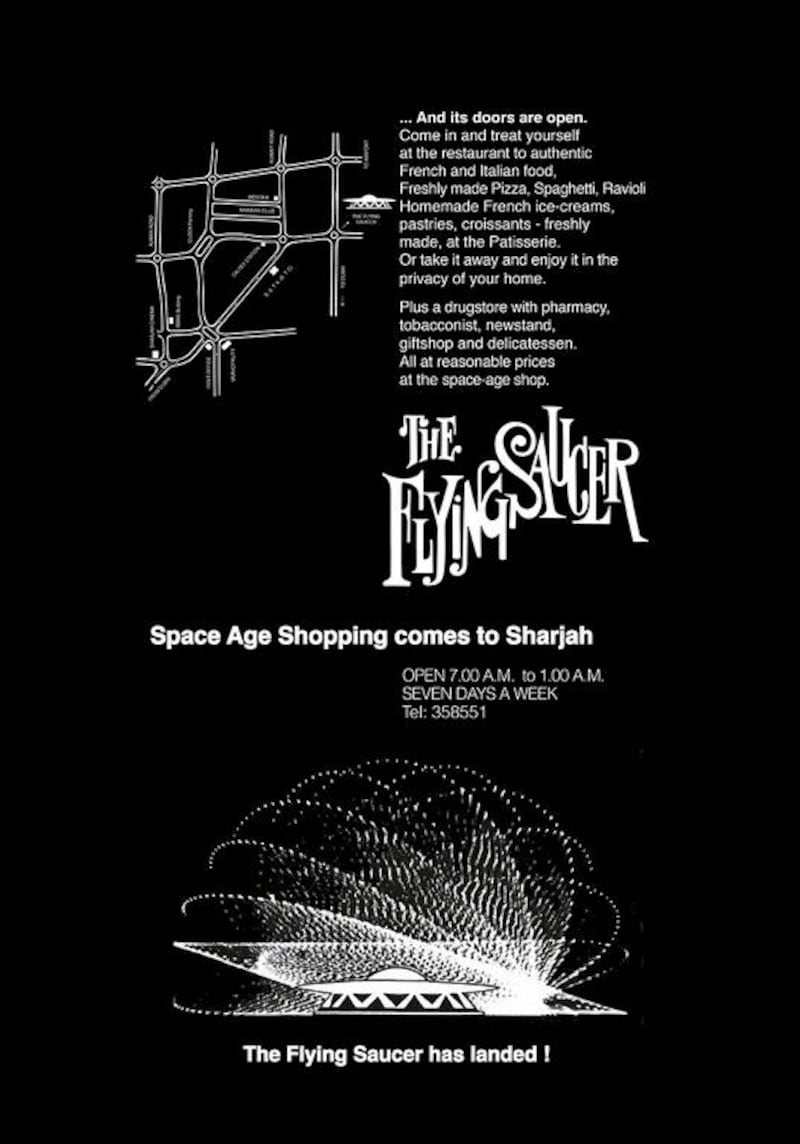

When the very latest word in shopping and dining opened in Sharjah in December 1978, the project’s unknown architect, charged with combining a restaurant with a drugstore, pharmacy, newsagent, tobacconist, gift shop, patisserie and delicatessen together in a one-stop-shop, looked to nothing less than the cosmos for their inspiration.

“Space Age Shopping Comes to Sharjah” boasted a contemporary advertisement in the Khaleej Times. “The Flying Saucer has landed!”

A fantastical blend of futurism and traditional Mediterranean hospitality, the new venue promised “authentic French and Italian food, freshly-made pizza, spaghetti, ravioli, homemade French ice-creams, pastries, croissants – freshly made, at the patisserie”.

Thanks to the then 28-year-old French patisserie Gérard Reymond, who ran the Flying Saucer before he established his Gérard Café chain in Dubai in 1981, the restaurant’s culinary promises were as genuine and innovative as the building itself.

The Flying Saucer’s light interior is made possible by an ingenious, triangulated “diagrid” of intersecting columns that allow its domed and 32-point concrete roof to seemingly float above its diaphanous, fully-glazed facade but the effect is a trick.

The central dome, which generates an unnerving, high-pitched echo, is supported on thin columns but the construction technique, a version of which can be seen in buildings such as Foster + Partners’ 30, St Mary Axe, more commonly known as The Gherkin in London, not only provides the Flying Saucer with illustrious structural stablemates but also means the building is ideally suited to its new role as a flexible and well-lit gallery.

The Flying Saucer’s flexibility is just one of the many reasons why the building is so appealing to Sheikha Hoor bint Sultan Al Qasimi, curator of 1980-Today: Exhibitions in the United Arab Emirates, the exhibition which opened at the venue on Saturday.

President and founder of the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF) and head of the internationally-respected Sharjah Biennial, Sheikha Hoor originally curated the exhibition, which features work by artists such as Hassan Sharif, Mohammed Kazem, Najat Meky and Moosa Al Halyan, for the National Pavilion UAE la Biennale di Venezia at the 56th International Art Exhibition in 2015. This is the first time that the exhibition has been displayed in the UAE.

For Sheikha Hoor, however, who first acquired the building while it was still in use as a Taza takeaway chicken restaurant, the Flying Saucer is rather more than just an addition to the SAF’s expanding property portfolio.

“We’ve been looking at buildings that we were worried about for a while because they were becoming neglected or might end up being demolished and we are seeing more of that,” explains the woman who was listed as one of the contemporary art world’s most influential figures in the 2015 ArtReview Power 100.

“But I remember walking into the Flying Saucer when it was Lal’s supermarket, it was quite dark, and I bought a little doll,” she says.

“We got the building four years ago but we kept renting it back to Taza because we didn’t have the budget to do anything with it.”

Although this is the first time that the Flying Saucer building has been used for a stand-alone exhibition, it was used by the SAF in 2015 during Sharjah Biennial 12 when it housed several works by the Cairene artist Hassan Khan and the satirical Egyptian cartoonist Andeel.

“We decided that it was time to use the building, but Hassan didn’t want to do anything to it, so it was left as it was,” explains Sheikha Hoor.

“But I really wanted to clean the building up to get it to a state where we could use it, similar to how I remember it from the 80s.”

For the current show, a new concrete floor and temporary walls have been installed and the Flying Saucer’s old shop fittings and false ceiling have been removed but the results, Sheikha Hoor insists, are only temporary.

“I think that a lot of interesting sound and movement works could take place there but I don’t want to limit its use and we don’t want to just use it for the Biennal,” she says.

“We could use it for workshops, for performances, we can use it year round but we really want to engage with the community.”

It is her desire to engage Sharjah’s various local communities and to do so on their own terms that has encouraged Sheikha Hoor to acquire buildings in much the same way that she collects contemporary art, with a consideration for their effect.

“We really have to concentrate on the local audience. That’s our mission really, to educate and to enrich the community around us, and I think its best to find a way to work with what you have,” she says.

“We want people to feel that this space is theirs. We’re a non-profit government institution and we’re not building new buildings or franchise museums, it’s really just about creating community spaces and exhibitions and artist interventions.”

There is also, Sheikha Hoor admits, a passion for the past that she shares with her father, Dr Sheikh Sultan bin Mohammed Al Qasimi, the Ruler of Sharjah.

“I hate change. I like it sometimes but very rarely, and my father and I have this, some people call it nostalgia,” she says.

“And my dad is also a historian. He protects our older buildings, but I tell him that for us, the sixties and seventies is our history.

“But our history is not really written and if you are reading about it it’s very one-sided so this is like writing our history through buildings and stories, which is why our architectural history is important.”

The result is a growing list of rescued, recycled and occasionally rebuilt structures across Sharjah now owned by the SAF that include abandoned ice factories in Kalba and Dibba Al-Hisn, studios on the site of the old Al Hamriyah fruit and vegetable market, an empty cinema in the port town of Khor Fakkan, a 1930s radio station in Sharjah city and a 1960s house and farmstead in Al Maqam.

Sheikha Hoor’s collection has got to a stage, she admits, where local authorities and government ministries now approach her with suggestions of structures that might be of interest.

“First I worked with some people from the heritage department but people really know what I’m looking for now,” she says.

“With the house in Al Madam a guy from the heritage department came to me and said ‘Look, there’s this house from the sixties and I think you would like it’ but each town has a planning department so I go myself and I talk with them and I think they appreciate that.”

The kind of community-focused effect that reusing these structures can have, Sheikha Hoor insists, was seen last year during Sharjah Biennial 12 when the Argentine artist Adriàn Villar Rojas mounted a major installation, Planetarium, in an abandoned ice factory in Kalba on Sharjah’s east coast.

“I was showing my father Google images and I searched under Kalba ice factory, just to see the public response, and he really liked what he saw,” the SAF president says. “A lot of people came to Kalba just for Adriàn’s installation, they were coming from all over. I knew it would be really good for the town because before nobody knew about Kalba and now they do.”

If the effect of the Kalba installation was short-lived, Sheikha Hoor hopes she can achieve something more enduring in Khor Fakkan, where the SAF has acquired a beautiful but dilapidated cinema whose facade bears a striking low-relief frieze featuring gazelle, palm trees, coffee pots and dhows.

“I think its important to have projects that are not token but that really focus on the town. A lot of actors on TV come from Khor Fakkan, it’s a big theatre town, so I’d really like to turn the building back into a working cinema,” she says.

“I’d also like to turn it into a public film school. It’s not really be about having a degree in film making but about being a place where anybody can apply and learn and take courses.”

It took Sheikha Hoor four years to acquire the Flying Saucer building and the cinema in Khor Fakkan but the process of obtaining each was very different.

Unlike the Flying Saucer, which was government owned, the cinema was in private hands and required lengthy negotiations before the owners agreed to swap their land in Khor Fakkan for property in Sharjah city. The process, however, offers a model of how historic structures might be saved elsewhere in the emirates.

“The building is in such bad condition, and every day I have people telling me that it would be cheaper to tear it down and rebuild it,” the Sheikha explains.

“But I was trying to exchange land in Sharjah for their property in Khor Fakkan, which wasn’t particularly good land. It isn’t a beachfront property and it isn’t facing the sea but we eventually sorted it out for them and now the land that they have is worth so much more,” she says. “They say they pray for me every day!”

nleech@thenational.ae

• The Sharjah Art Foundation have launched a research project that will look at the urban history of the Flying Saucer building. If you have any photos, press cuttings, written or recorded memories or even architectural plans, please submit these to The Flying Saucer Memorabilia project by emailing submissions@sharjahart.org

• 1980-Today: Exhibitions in the United Arab Emirates is on display at the Flying Saucer Building, Dasman, Sharjah until 14 May 2016. Visit www.sharjahart.org for more details.