OSAKA // More than 70 years ago, at age 14, Kim Bok-dong was ordered to work by Korea's Japanese occupiers. She was told she was going to a military uniform factory, but ended up at a Japanese military-run brothel in southern China.

She had to take an average of 15 soldiers per day during the week, and dozens over the weekend. At the end of the day she would be bleeding and could not even stand because of the pain. She and other girls were closely watched by guards and could not escape. It was a secret she carried for decades; the man she later married died without ever knowing.

Tens of thousands of women had similar stories to tell, or to hide, from Japan's occupation of much of Asia before and during World War II. Many are no longer living, and those who remain are still waiting for Japan to offer reparations and a more complete apology than it has so far delivered.

"I'm here today, not because I wanted to but because I had to," Kim, now 87, told a packed audience of mostly Japanese at a community centre in Osaka over the weekend. "I came here to ask Japan to settle its past wrongdoing. I hope the Japanese government resolves the problem as soon as possible while we elderly women are still alive."

The issue of Japan's use of women and girls as sex slaves - euphemistically called "comfort women" - continues to alienate Tokyo from its neighbours. It is a wound that was made fresh this month when the co-head of an emerging nationalistic party, Osaka Mayor Toru Hashimoto, said "comfort women" had been necessary to maintain military discipline and give respite to battle-weary troops.

His comments drew outrage from South Korea and China, as well as from the US State Department, which called them "outrageous and offensive."

Mr Hashimoto provided no evidence but insisted that Tokyo has been unfairly singled out for its World War II behaviour regarding women, saying some other armies at the time had military brothels. None of them, however, has been accused of the kind of organised sexual slavery that has been linked to Japan's military.

Historians say up to 200,000 women from across Asia, including China, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Myanmar, Hong Kong and Macau, as well as the Netherlands, were forced to provide sex for Japanese soldiers.

To many people, even within Japan, Mr Hashimoto's comments suggest that Japan refuses to fully acknowledge wartime wrongs, leaving it out of touch with many of their own citizens.

"It's not a problem of the past. It's a continuing problem that involves people who are still alive," said Koichi Nakano, a Sophia University political science professor. "Japan is perceived as merely waiting for them to die while looking the other way and dragging its feet. That looks bad from a humanity point of view."

According to a survey conducted over the weekend by the conservative Sankei newspaper and FNN television, more than 75 per cent of Japanese said Mr Hashimoto's sex slave remarks were inappropriate, while support for his party slumped to 6.4 per cent - nearly half what it was last month.

In 1993, Japan officially apologised to "comfort women" in a statement by then-Chief Cabinet Secretary Yohei Kono, acknowledging "immeasurable pain and incurable physical and psychological wounds".

But Kim and other women want a full apology approved by parliament and official compensation from the government. Tokyo has resisted that, saying war reparations with South Korea were dealt with in treaties restoring relations after the war. In Japan, much of the debate still focuses on what role the government at the time played in organising brothels.

Nobuo Ishihara, who was then deputy Cabinet secretary, said in March 2006 that interviews with 16 South Korean women in Seoul led to the conclusion that there was systematic coercion by the government even though there were no official documents showing so.

"After interviewing the 16 comfort women, we came to believe that what they were saying could not be fabrication. We thought there was no doubt they were forced to become comfort women against their will," Mr Ishihara said. "Based on the investigation team's report, we concluded that there was systematic coercion by the government."

Mr Hashimoto, 43, sought to calm the uproar on Monday, telling a news conference that he personally did not condone using "comfort women," which he labelled a violation of human rights.

But he repeatedly insisted that Japan's wartime government did not systematically force girls and women into prostitution.

Mr Hashimoto acknowledged that this murkiness probably is the key stumbling block in Japan's ties with South Korea.

Kim was dragged across Asia, from Hong Kong to Singapore and Indonesia, until the end of the war in 1945. She was freed in Singapore and returned home in 1946. She later was married but - like most former sex slaves - was never able to reveal her past to anyone but her mother - until decades later.

"Even as I returned to my homeland, it never was a true liberation for me," she told listeners at the community centre. "How could I tell anyone what had happened to me during the war? It was living with a big lump in my chest."

She finally broke her silence several years after her husband died in 1981. Later she joined a group of women seeking official recognition as victims of Japan's sex slavery.

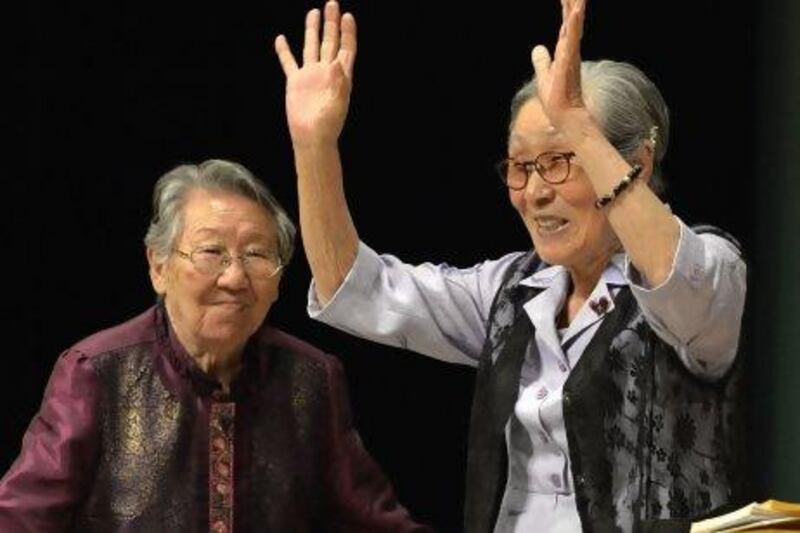

Kim and another former sex slave, 84-year-old Kil Won-OK, had been seeking a meeting with Mr Hashimoto for some time when he made his comments this month. He then offered to meet them, but they cancelled.

"We won't be around much longer," Kil said. "But we have to tell you our stories because we don't want the same mistake repeated again."