Every week the headlines tell a similar story, from Mexico to the Congo to North Korea, of murderous gangs and tyrants threatening apocalypse.

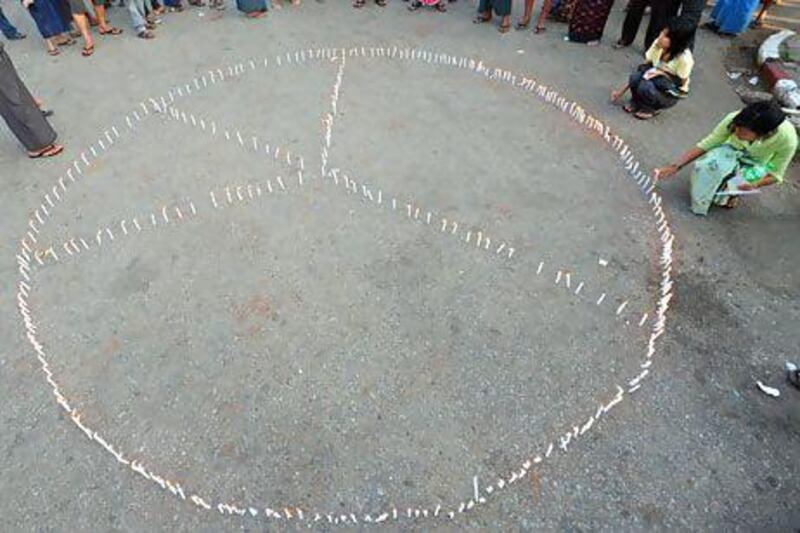

In the face of such endless barbarism, what possible purpose can be served by this week’s inaugural meeting in Dubai of the Peace and Sport Middle East Forum?

Cynics will dismiss it as a talking shop that achieves little except to give its celebrity delegates a nice warm feeling. Yet if they achieve nothing else, those attending should do their utmost to highlight one of the most shocking stories of the past half-century: the world is becoming a more peaceful place.

In light of endless reports of wars, terrorism and atrocities, the very suggestion that people are steadily being nicer to each other seems preposterous. Yet the evidence has been accumulating for centuries.

Not that one gets universal praise for pointing it out. Just ask Prof Steven Pinker of Harvard University, whose presentation of the evidence in his latest book, The Better Angels of Our Nature, sparked a backlash from academics and pundits alike. He stood accused of everything from using dubious measures of violence to cherry-picking data and – most heinous of all – risible optimism.

Prof Pinker’s evidence is certainly eclectic, ranging from studies suggesting a collapse in both the frequency and duration of wars involving major nations since 1500 to an even more impressive decline in the use of execution to punish crimes in the US over a similar period.

These trends, he argues, are the product of humans creating an environment that allows freer expression of our “better angels”, a phrase taken from the speech given by the former US president, Abraham Lincoln, when he took office in 1861.

In particular, Prof Pinker identifies certain factors that are driving the move away from recourse to violence. He cites studies suggesting a link between the rise of literacy, democracy and international trade and declining violence, along with increasing concern about the rights of children, women and animals.

While the debate about his evidence continues, Prof Pinker remains steadfast in his rejection of the notion that humans are natural-born Darwinian killers.

As for the charge of optimism, he insists that while he stands by his evidence, final victory of our better angels is far from assured: “Violence has been in decline for thousands of years”, he says, adding darkly that this decline “is not guaranteed to continue”.

Yet new research suggests that it is the pessimists who will be proved wrong. Not only does it confirm that the world has been getting less violent, as Prof Pinker asserts, but it suggests that he – and we – can be more hopeful that the trend will continue.

Dr Havard Hegre and his colleagues at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (Prio), in Norway, have examined the most common form of armed conflict over the last 50 years: wars not between nations, but within them.

Reports of such internal strife is all too familiar, but according to Dr Hegre and his colleagues, it too may succumb to our better angels.

And, like Prof Pinker, the team believes the presence of these angels can be discerned through quantifiable factors – such as infant mortality, education levels and the proportion of young people in the population.

History shows that such internal issues are not enough to determine the success of the angels in any given nation. Factors such as political independence and the stability of neighbouring countries are also important.

So the Prio team collected data on these factors as well, and has combined them to create a mathematical model of the risk of internal strife in specific regions.

To test out its reliability, the team used data on the factors from 1970 to 2000 to predict the outbreak of violence in the world’s 169 nations in 2009.

The results, published recently in the statistics journal Significance, are impressive. Of the 26 countries riven by strife in that year, the model correctly identified 16 – a hit rate of 63 per cent.

At the same time, it incorrectly predicted trouble in just 4 of the remain 143 nations; a “false positive” rate of less than 3 per cent.

So what of the future? On a global scale, the model’s forecast is unambiguous. Given that future trends are towards reduced infant mortality and better levels of education, plus the fact that peace begets more peace, conflicts are set to decline markedly over the coming decades.

On a regional basis, the picture is more complex. For instance, two regions south of the Sahara – west Africa, and east and central Africa – are unlikely to show any clear reduction in conflict in the near future; indeed it looks set to increase over the next few years.

The reasons are not hard to find: these are regions with dire levels of infant mortality and high proportions of male youths with no secondary education.

Yet still there are grounds for hope: according to the Prio model, these regions are likely to join the global trend towards peace within 20 to 30 years.

Like Prof Pinker, the researchers stress that there are no guarantees. A deep and persistent global recession, or dramatic climate change could derail the forecasts for the drivers of peace.

Technological changes could also fuel new conflicts based on resources. Who could have foreseen, for example, that the mineral resources needed for mobile phone technology would now be driving the continuing war in the Democratic Republic of Congo?

Cynics will still dismiss the Prio model as being no less optimistic about human nature than Prof Pinker. After all, is not the evidence in those stories of strife everywhere from Mexico to the DR Congo?

But here’s a thing: the numbers of drug-related murders have plunged since Mexico’s new president came to power last December.

Meanwhile, in the DR Congo, Bosco “The Terminator” Ntaganda, the notorious warlord, last month gave himself up and is now on trial at the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

So perhaps the cynics should take themselves along to this week's Peace and Sport Middle East Forum. They might just learn something about those better angels.

Robert Matthews is visiting reader in science at Aston University, Birmingham, England