India’s space agency is preparing to launch its second mission to the moon, even as its ambitions shift away from pure civilian research towards military and commercial purposes.

Chandrayaan-2 will lift off in the early hours of Monday from Sriharikota, the Indian Space Research Organisation’s launch facility on the eastern coast. The mission will deploy an orbiter around the moon; set down the first-ever lander near the lunar south pole; and push out a rover, named Pragyaan (the Sanskrit for “wisdom”), to collect data.

The mission is a sequel to Chandrayaan-1, which launched in 2008 and went on to discover the widespread presence of water in the moon’s soil.

But Chandrayaan-1 only employed a probe that crashed on to the surface and took its measurements there. This time, the lander aims to touch down slowly and softly, so that Pragyaan can emerge undamaged.

“Those 15 minutes [of the soft-landing] would be the most terrifying moment for us,” K. Sivan, chairman of the ISRO, told reporters last month. “Even a fraction of a second should not go against the plan. It is going to be the most difficult task ISRO has ever undertaken.”

Only the US, Russia, and China have successfully carried out lunar soft-landings before. Israel attempted one in April but failed after its lander crashed.

Pragyaan will use spectroscopes to assay the lunar soil for its mineral content. The lander and orbiter carry a range of instruments as well, including a retroreflector from Nasa, the US space agency, to improve measurements of Earth-Moon distances.

"The Chandrayaan-2 mission will help us understand [the Moon's] origin, evolution and chemical composition," Joice Mathew, a scientist at the Advanced Instrumentation and Technology Centre in Canberra, Australia, told The National. "It will be a stepping stone to India's deep space exploration."

As is customary with ISRO missions, all the equipment and instruments for Chandrayaan-2 were developed indigenously. The mission's cost is roughly $143 million — less than half the budget of the film Avengers: Endgame, as one Indian news web site pointed out.

This has always been ISRO’s strong suit: low-cost, home-engineered missions that have conducted fundamental research for a small fraction of the price of other national space projects.

When ISRO was founded in 1969, its vision was tied closely to that of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who had called for a national space programme seven years earlier. ISRO would pursue research and planetary exploration, but it would also seek to “harness” space technology to develop India.

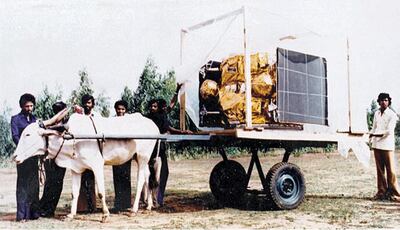

Accordingly, ISRO’s missions sent up satellites that aided in communication, meteorology, mapping forest cover, urban sprawl and crop production. It did all this frugally — so much so that the most famous photo produced by ISRO shows a satellite being transported by bullock cart. But ISRO’s rockets always launched and its satellites always slipped cleanly into orbit, so its reputation for inexpensive efficiency was well-earned. The agency’s commercial arm, Antrix, now launches satellites for other countries including Canada, France and Germany.

“India’s comparative advantage lies in its low cost of production, particularly the low costs of engineers and other technical persons,” said Ulaganathan Sankar, a professor at the Madras School of Economics and the author of a book about ISRO’s economic model. But he said the nature of that advantage is changing.

A number of satellite launch companies in the private sector around the world are now competing with Antrix, in a market expected to be worth around $28 billion by 2025.

“I think ISRO will still be the cost-effective launcher,” Dr Mathew said. But it’s crucial, he said, for the agency to stay at the forefront of technology by improving their reusable rockets, using 3D printing to manufacture components, and co-operating with private companies to stay sharp.

Others think, though, that India’s space programme is honing another of its edges as well.

Over the last few years, India has been developing its military potential in space, “as reflected in its new fleet of military satellites,” said Namrata Goswami, an independent analyst of space policy. Dr Goswami cited India’s test of an anti-satellite missile in March, and its launch of a Defence Space Agency in June as evidence of this shift.

“The economic and military rise of China and its [anti-satellite missile] tests have convinced India that its satellites and territory are vulnerable and require a military space programme,” she said.

India is also working on Gaganyaan, its first mission to place humans into orbit, scheduled in 2021.

These new endeavours reflect the hyper-patriotic, militaristic zeal of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government since 2014. India’s space programme has always had a component of national pride, Dr Goswami said. “Today’s flavour of nationalism clearly interprets its space endeavours as part of the jockeying for relative power and status in the global order.”

At the same time, India’s own private sector is throwing up a raft of space start-ups, many of them drawing upon the talents of the country’s information technology industry. A Bengaluru-based company, Team Indus, was one of five finalists in Google’s Lunar X Prize. (The top prize of $20 million went unclaimed.) Team Indus is also part of an international group of companies that will design and build a Nasa lander for a Moon mission in 2020.

Last year, in the first major contract of its kind, ISRO farmed out the assembly and manufacture of dozens of satellites to private companies. Another Bengaluru firm, Bellatrix Aerospace, is working with ISRO to develop a water-based propellant for satellites. Bellatrix recently raised $3 million from investors — the largest venture capital investment in space tech in India thus far.

There is still some “turbulence” in the interactions between the government’s space sector and these companies, Dr Goswami said. There is “a lack of clear legal and regulatory structure to encourage investment, protect intellectual property, and establish liability.”

But the energy is unmistakable, she said. “There is an emerging narrative that India has a manifest destiny in space, and that it should seek to be the first among nations, and lead in new space endeavours.”